When I was invited to give a speech in Florida this month as part of a fiftieth anniversary commemoration of the decision in Gideon v. Wainwright, the first thing I did, of course, was to pull out my tattered copy of Gideon's Trumpet, Anthony Lewis's superb and evergreen account of the story behind the Supreme Court case guaranteeing indigent criminal defendants a right to counsel.

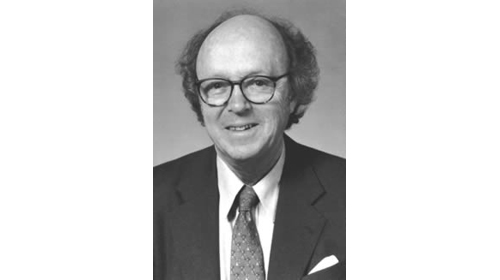

We are now so accustomed to seeing books that recount the story of a significant case or that peer behind the scenes at the Supreme Court that it is easy to forget that it was Anthony Lewis who pioneered this genre. Lewis, who passed away this week, used his full range of reportorial and writing skills, as well as his acumen as an observer and analyst of law, in making his anatomy of Supreme Court litigation into a page turner. It may have been the lawyers – Abe Fortas and John Hart Ely representing Gideon and J. Lee Rankin and Norman Dorsen filing an important ACLU amicus brief – who won Gideon in court, but it was Anthony Lewis, the peerless communicator, who was largely responsible for winning over the public in his 1963 reporting and in the 1964 book that has never gone out of print.

Lewis's choice of the Gideon case as his vehicle for teaching about how the Supreme Court works had the not incidental side effect of helping a form of justice take root through sympathetic public awareness. His message continued to resound. Gideon's Trumpet became the basis of a television movie on the Hallmark Hall of Fame, starring American film icon Henry Fonda as the irascible pool hall drifter -- a bit of insurance that there would be less backlash against the very idea of a right to assigned counsel than there has been against other Warren Court criminal procedure innovations. Two years later, Lewis wrote a version of his book for children, the future consumers and guardians of civil liberties: The Supreme Court and How It Works: The Story of the Gideon Case. And today, the Gideon decision is the subject of adulatory displays in the halls of the Florida Supreme Court, at the heart of the very court system that had denied Gideon a right to counsel.

And this was only one chapter in Lewis's lifelong work of simultaneously educating the public about law and promoting civil liberties. As a New York Times reporter, Lewis won his first Pulitzer Prize in 1955, at the age of 28, for telling the story of a civilian employee of the Navy falsely accused of being a Communist sympathizer – and using that story to show the public what was noxious about McCarthyism. He won a second Pulitzer Prize in 1963 for his transformative reporting on the Supreme Court, helping to make the Court's critical work more comprehensible and more transparent to lawyers and non-lawyers alike. The journalists who are now covering every angle of the Supreme Court marriage cases may not know it, but they are walking a trail blazed by Anthony Lewis.

As the years went on, Lewis paid particular attention to explaining and championing the First Amendment freedom of speech and of the press, in his reporting, in his public speaking, and in several excellent books (Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the First Amendment in 1991 and Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment in 2010). As a teacher and scholar of journalism, he also engaged in sophisticated academic efforts to define the appropriate boundaries of these rights.

In December 2001, three months after 9/11, Lewis retired from the New York Times and wrote presciently in his valedictory column: "The hard question is whether our commitment to the law will survive the real sense of vulnerability that is with us after September 11." For the rest of his life, he lent his voice to a wide range of efforts to ensure that our commitment to law and to our principles would indeed survive the fears and passions of our day. When I wrote my book about the impact of 9/11 on the liberties of ordinary Americans, Lewis was generous enough to write a review for the book's back cover. After expressing his anger at "what American politicians have done to our freedoms since Sept. 11, 2001," he commended my book for explaining what had happened and ended by saying something that seems to me to be a suitable motto for his own life's work: "Read her and think." Not "Read it and weep." A true and essentially optimistic patriot, Lewis seemed always to believe that if we just learn enough and think enough, we will be able to do the right thing instead of just weeping over our mistakes.

Anthony Lewis was a friend of the American Civil Liberties Union as well as of American civil liberties. In 2003, we were proud to recognize his substantial lifelong contributions to civil liberties by awarding him the ACLU's highest honor, the Roger N. Baldwin Medal of Liberty. I am glad that we were able to show him in this way how highly we valued him.

Along with so many others, we at the ACLU will miss his ardent and articulate voice and his exemplary devotion to liberty and justice.

Learn more about indigent defense and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.