New York City Transit President Andy Byford announced this week that he would ask the city, including the police, to help respond to homeless people exhibiting “offensive, obnoxious and anti-social” behavior on subways.

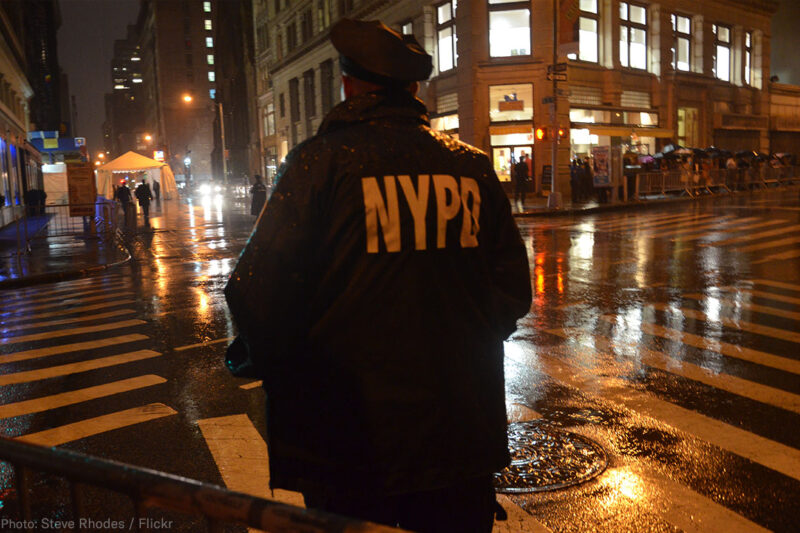

The comments prompt fresh concerns that the NYPD could exacerbate the city’s already problematic track record of criminalizing homeless people.

“There is a fundamental difference between someone coming in to keep warm and sitting on a seat and dozing off, I don’t really have a problem with that,” Byford said at a Metropolitan Transportation Authority board meeting. “But laying across a seat or behaving in an antisocial manner or making a mess is not acceptable.”

Byford added that people “being offensive, obnoxious, and anti-social” is something “we are not prepared to tolerate.”

It remains to be seen how these comments from Byford will be interpreted by the city’s transit employees and the NYPD. And Byford did mention that he remains committed to making sure homeless people in the subways get “the help they need.” After his initial comments made headlines, Byford further clarified that he was not calling for a “blitz” or “mass eviction” of homeless people.

But having police confront people exhibiting “anti-social” behavior still sets off alarm bells. What is the criteria for determining who is displaying such behavior? What will the police do when they’re called upon to handle these situations?

Much of the concern around these comments arises because of the NYPD’s history of criminalizing and demeaning homeless people.

The New York Civil Liberties Union filed a complaint two years ago asking the New York City Commission on Human Rights to investigate the NYPD’s practice of forcing homeless people in Harlem to “move along” from place to place, sometimes threatening them with arrest. The people repeatedly hounded by the NYPD hadn’t violated any laws and were simply present on streets, sidewalks, and in other public spaces.

Forcing people who are doing nothing wrong to move in this way violates the city’s Community Safety Act, which prohibits “bias-based profiling” that includes targeting people based on their housing status. Homeless New Yorkers have the same right to use public spaces as everyone else. The complaint is still pending before the commission.

Last year, the NYCLU announced a settlement on behalf of three homeless people who were kicked awake, at which point NYPD officers and sanitation workers threw out their social security cards, birth certificates, and medication.

And the same week that Byford made his comments at the MTA meeting, the New York Daily News reported that the NYPD is adding new surveillance cameras in a part of Manhattan’s Upper East Side “where homeless people tend to congregate and have been accused of various quality of life infractions.” Quality of life infractions include things like drinking a beer on the sidewalk.

Aggressive enforcement of these types of minor infractions have historically pushed hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers into the criminal justice system. Two years ago, the city passed legislation designed to move the city away from a focus on these types of offenses, making reports about these cameras and purpose particularly discouraging. Poor and homeless New Yorkers have always been disproportionately targeted for minor infractions.

Police should not be on the frontlines of dealing with the crisis of more than 60,000 New Yorkers living without homes. Effectively addressing this humanitarian emergency, which has been spurred by a dearth of affordable housing, will require a society-wide response, as Byford himself acknowledges.

Time will tell what impact Byford’s comments have on homeless New Yorkers, but the NYPD cannot be allowed to criminalize homeless people simply for existing.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.