Baltimore Aerial Surveillance Program Retained Data Despite 45-Day Privacy Policy Limit

The operators of the aerial mass-surveillance system that has been flying over Baltimore since January have apparently been indefinitely retaining all the images captured by the surveillance aircraft, despite promises that those images would be destroyed after 45 days.

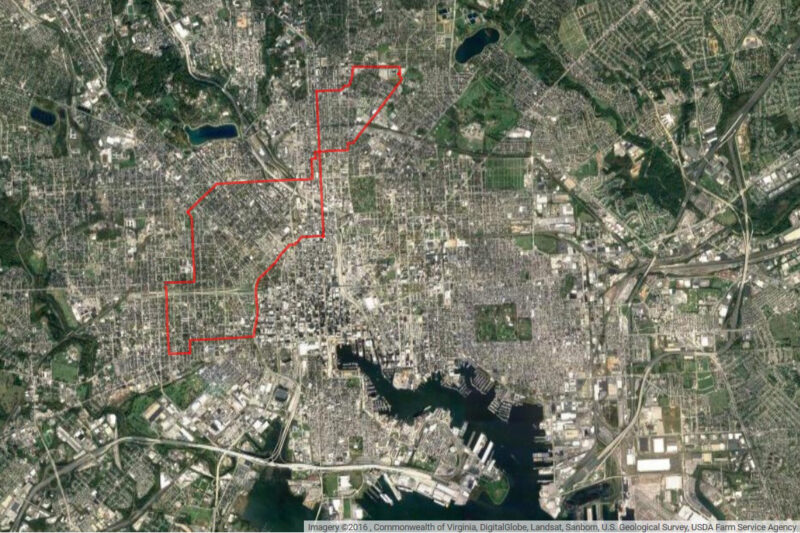

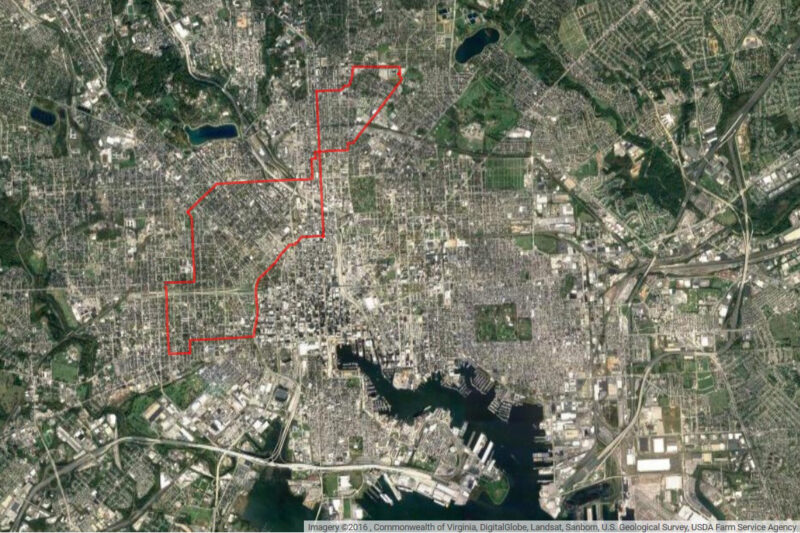

Since the aerial mass-surveillance program was revealed in late August to an immediate firestorm of controversy, one of the biggest questions has been: how long is the aerial photography retained? The system involves the deployment of megapixel cameras on a Cessna aircraft, which circles over a city for up to 10 hours at a time, continuously photographing a 30-square-mile area. This is a technology that promises to do for our physical movements what the NSA has aimed to do with our communications: collect it all.

From the time the existence of this massive surveillance program was revealed in August, the program’s operators have been touting the privacy protections that are supposedly in place, and assuring the public that they are sufficient. In particular, they have been claiming that the imagery is retained for 45 days unless it is part of an investigation. An online Baltimore police FAQ states:

How long do you keep the data?

We keep our imagery data for 45 days unless there are ongoing investigations or prosecutions associated with the data.

But a new document indicates that’s not the truth. One of the groups that has been very concerned about the secrecy of this program is public defenders in Baltimore. As public defender Kelly Swanston put it in a Baltimore Sun op-ed,

Our office did not know the BPD was working with the Community Support Program to collect data on our clients' movements and then using the data to charge our clients with crimes without disclosing the source of the evidence. For our innocent clients, we missed opportunities to subpoena exonerating footage collected by the spy plane. For our clients who were mistreated by officers, or whose versions of the truth differed from an officer's report, we failed to corroborate the truth because we did not know that a plane had captured footage of the city. The BPD, and by extension the Baltimore City State's Attorney's Office, had data that likely could have corroborated our clients' innocence in the face of an officer's inconsistent statement, but they decided to keep it a secret….

Hiding the technology and surveillance systems used to solve crimes does not create a fairer justice system; it encourages officers to leave material facts out of reports and to lie about the real probable cause for locating someone, and it deprives people of access to evidence that could lead to their exoneration. If individuals knew about the documentation of their movements, they could subpoena the footage when an officer gives an untrue account of a police encounter.

Acting on such concerns, the Baltimore Office of Public Defenders sent an Aug. 26 letter to Police Commissioner Kevin Davis asking for the “retention protocol for surveillance data” as well as various other information about the program. And, the public defenders asked the commissioner to preserve data in case it is helpful in exonerating suspects.

In a Sept. 20 response, Davis told the Office of Public Defenders that

Vendor, Persistent Surveillance Systems (PSS), has verified that all images recorded/captured during the pilot program have been saved and archived and are therefore available, regardless of whether the images were provided to BPD for use in investigations. [emphasis in original]

This clearly contradicts the retention policy stated on the Baltimore police FAQ. According to a flight times summary document also provided to the public defenders, the pilot program has been underway since January 13, 2016, when the first flight was conducted. If, as Davis writes, “all images recorded/captured during the pilot program have been saved and archived,” then clearly no 45-day retention policy was ever followed. The period of time from the first flight (Jan. 13) to the day Davis responded (Sept. 20), was 251 days, and apparently the program’s operators are holding imagery recording Baltimore residents’ comings and goings from that entire period, and continuing to the present.

The retention policy is one of the critical questions with regard to any surveillance program because the longer data is retained, the greater the opportunities for misuse and for repurposing of the data into new uses that can harm people in new and expanded ways. To be clear, we do not think this program should be operating at all. But it becomes even worse the longer the imagery is retained.

Two other items of note about the Baltimore surveillance program since I last wrote about it.

First, the Baltimore Sun has reported that Persistent Surveillance Systems (PSS), the company operating the program, is considering marketing the surveillance data that his company collects to insurance companies. This raises numerous new issues aside from those raised by government surveillance. After all, this is a system that could become capable of recording all manner of lifestyle data about people, including:

- How often various drivers break the speed limit.

- Who goes to the gym every day, and who goes once a month

- Who goes to bars once a month, and who goes every day.

- Who eats fast food and who shops at health food stores.

And many other things. When I met with PSS president Ross McNutt, he assured me that the system would only be used for “major crimes.” He may have been perfectly sincere at the time, but this is a lesson: that the logic of data capitalism has a momentum of its own, and limits are unlikely to stand unless they’re written into the law.

And speaking of my meeting with McNutt, his company and the Baltimore Police have been citing that in a misleading way. Boasting of their supposedly “strict and comprehensive privacy policy”—which as we have seen appears to be less than strict—the program’s FAQ states that “It was developed with input from a wide range of sources including local police departments, local community groups, State and National ACLU, and many others.” This implies that the ACLU has somehow approved or signed off on the policy; nothing could be further from the truth. McNutt asked to meet with me, I agreed, and told him what I thought the insoluble privacy problems were with wide-area surveillance. He may have taken account of my feedback in formulating his policy, and we can’t stop him from citing that feedback in its formation, but nobody should think that we are okay with this approach to law enforcement.