Civil Rights Movement Is a Reminder That Free Speech Is There to Protect the Weak

We at the ACLU are often criticized for our unyielding defense of free speech rights. Even our closest allies complain when we defend the free speech rights of Klansmen and assorted other racists, misogynists, online haters, fake news creators, and other toxic speakers. In particular, we hear that such defenses of free speech rights serve not to protect the weak but to protect the powerful in their attacks on the vulnerable.

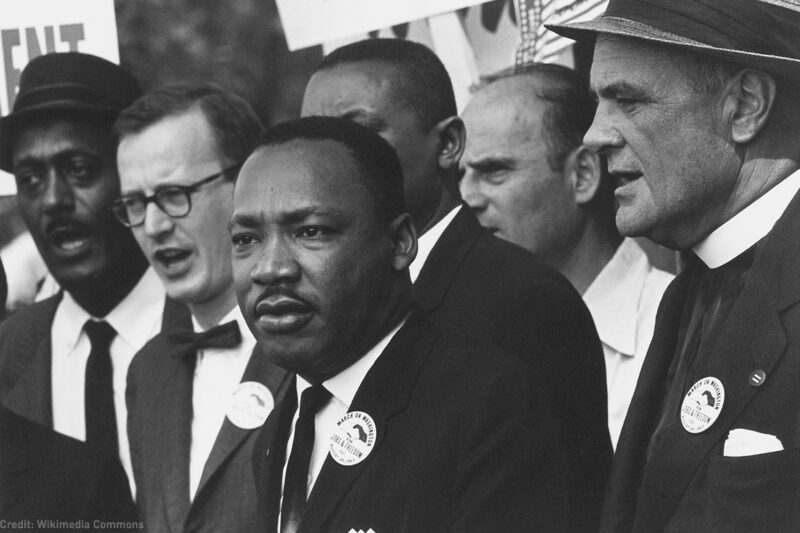

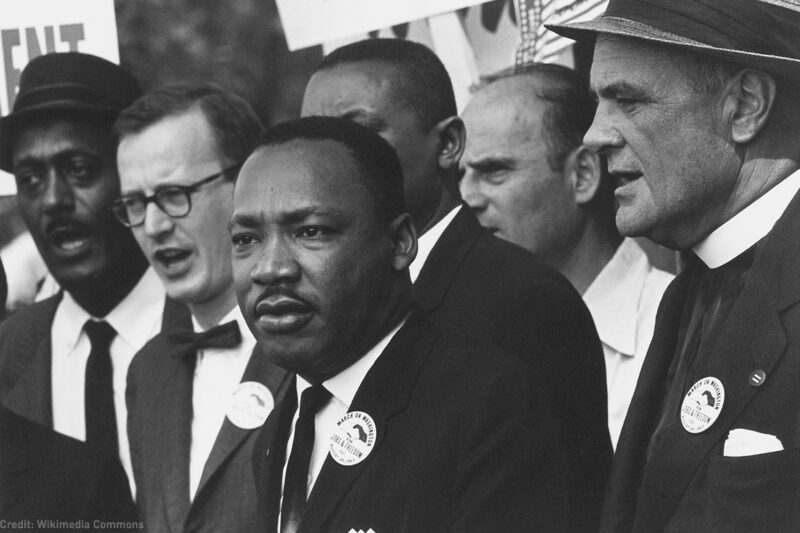

Recently I’ve been re-reading Taylor Branch’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Parting the Waters: America in the King Years,” a history of the civil rights movement with a focus on the life of Martin Luther King. I’d forgotten what a fantastic telling of the civil rights story it and its two sequels are. But also, rereading the story in light of my work at the ACLU, I’ve been struck by the injustice not only of segregation, “separate but equal,” and the deprivation of voting rights, but the key role that egregious violations of free speech rights played in Southern officials’ opposition to the movement. It’s a reminder that when you mess with First Amendment rights, it’s ultimately the weak and powerless who lose out the most, even when those rights do sometimes protect the powerful.

All across the segregated South, many thousands of Black Americans went to jail protesting segregation — and many of those who went to prison did so on the grounds that they were violating injunctions against protesting and assorted other unconstitutional restrictions on speech.

A key chapter in the movement, for example, was the “Albany Movement” of 1961 and 1962 in Albany, Georgia. At one point, when a group of prominent Black citizens went to pray for justice on the steps of city hall there, they were arrested. For praying. Several months later, Martin Luther King himself was also arrested in Albany for praying outside city hall for an end to segregation.

A year later, when the focus of the movement had shifted to Birmingham, Sheriff Bull Connor obtained an injunction from a compliant state judge ordering 133 specific people, including movement leaders, not to engage in “parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing,” or even “conduct customarily known as ‘kneel-ins’ in churches.” It was King’s violation of this injunction that landed him in prison for the stint during which he wrote the famous “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.”

In 1962, Robert Moses, the fearless and zen-like civil rights hero who circulated across Alabama and Mississippi trying to register Blacks to vote, was handing out leaflets in Sunflower, Mississippi, announcing a voter registration drive. He was arrested by police on the charge of “distributing literature without a permit.”

In February 1963, a suspicious fire destroyed several black businesses in Greenwood, Mississippi. When one local activist named Sam Block speculated that the fire was a bungled act of arson aimed at the SNCC offices next door, he was arrested by Greenwood police for “statements calculated to breach the peace.”

Later that year, John Lewis — the man now serving in Congress whom President Trump slammed as “All talk, talk, talk – no action or results” — was arrested in Selma, Alabama, for carrying a sign outside the courthouse that read “One Man/One Vote.”

In all these cases and many others like them, the violations of First Amendment rights were so flagrant that they would be laughable were they not such deadly serious business for the men and women risking their lives confronting segregation. Official defenders of segregation seemed to feel the need to keep up a pretense of legality by wrapping their arrests in a justification of injunctions or patently unconstitutional charges like “distributing literature without a permit.”

When activists were arrested for such things, civil rights groups often appealed to the Justice Department, headed by JFK’s brother Robert, but the political interests of the Kennedy Administration were for the whole thing to just go away. After all, Kennedy was elected by a Democratic coalition of White southerners, northern liberals, and Blacks that civil rights split wide open. The Kennedys didn’t want their popularity to collapse in the South, and they didn’t want to put their fellow Democrats the Southern governors in a bad position with federal intervention.

As a result, civil rights activists’ claims about the unconstitutional suppression of their speech had to wind their way through the court system largely without DOJ assistance. Because few southern judges were willing to uphold the First Amendment rights of Black Americans, it often fell to federal courts to uphold their rights, and that took time, during which charges could hang over activists.

In one famous case, a group of King supporters ran an ad in The New York Times appealing for donations for the civil rights cause. Among other things, the ad criticized the police in Montgomery, Alabama — although it contained several inaccuracies. In response, Montgomery police commissioner L.B. Sullivan filed a defamation lawsuit against top civil rights leaders, including Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth. This was part of a larger effort by Southern officials to use libel law to squelch press coverage of the civil rights movement. When Alabama courts ruled in favor of Sullivan, officials began to seize personal property — including automobiles and family land — from the civil rights leaders, driving several of them to move out of the South, including Shuttlesworth, who left his Alabama church to move to Cincinnati. The case hung over the activists (and the New York Times) for years until the Supreme Court finally dismissed Sullivan’s claims in the landmark 1964 free speech case New York Times v. Sullivan.

The illegitimate nature of the charges that were thrown at many civil rights activists has echoes today in the vague, catch-all charges like “disturbing the peace” that police often abusively levy against protesters and others that anger a police officer in one way or another. It also has echoes in the attempts of some in state legislatures to criminalize dissent in new and creative ways.

When the authorities are allowed to get away with such things, the people who pay most sharply are the people who are out in the streets, trying to push their country to become a better, more just place. It’s easy to think of the civil rights movement as a campaign against segregation, which it certainly was, but it was also a campaign for the full spectrum of rights, including freedom of expression. (And let’s not forget that civil rights activists’ privacy rights were of course also violated, most famously by the FBI with its wiretaps of not only of Martin Luther King but of other activists, too.) There was a reason it was called a “rights” movement.

As my colleague Lee Rowland recently pointed out, our free speech rights are indivisible, with civil rights leaders’ speech protected by the courts, for example, based on rulings protecting the speech of racists speaking at KKK rallies. If we don’t stand up for the First Amendment when racist speech is censored, it is the weak, the powerless, minorities, and those who seek change who will be hurt most in the end.

As I’ve argued before, it is in times of political turmoil and conflict when our civil liberties really get tested — when angry people who want to change the world hit the streets in protest, and others, such as police officers and other officials, feel contempt and hatred for those doing the protesting. The Sixties was one of those times. We’re arguably in the middle of another one. If we are, many protesters will have even more cause to be glad that our First Amendment rights are as solidly established as they are — and to hope they remain that way.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.