On August 1, Maryland resident Korryn Gaines began an armed standoff with police after they came to her apartment to serve a traffic warrant and she refused to let them in. And then she began recording the events and posting them online on Facebook and Instagram. Hours in, frustrated officers (who were not wearing body cameras) asked Facebook to turn off the switch to her accounts. And it did. And then officers shot and killed Gaines—leaving no digital record of her death.

Today we work, live and speak in a digital world. Mobile phones and Twitter have replaced megaphones and town greens. But something funny happens on the way to this (digital) forum: we must first step onto private property to make our voices heard. Before your voice is heard online, you must depend on a private company—usually, a social media platform—to faithfully publish your post.

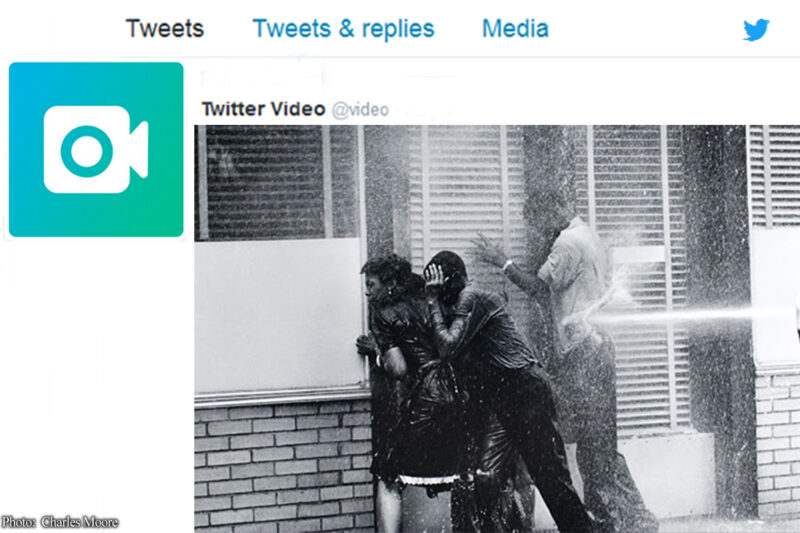

Images on social media have enormous power. Which is why we need to ensure that private companies can’t turn off the switch whenever they choose.

The current vitality of today’s Black Lives Matter movement has in part been fueled by the onslaught of repeated, searing images of police shooting unarmed people of color. Feidin Santana shot the harrowing cell phone video of Walter Scott’s killing by a Charleston police officer—and then connected with Black Lives Matter activists on social media to share the video. After Freddie Gray’s death, activists in Baltimore stormed the streets—and documented their protests on Periscope (so successfully that mainstream media offered a guide to the best livestreams). The traumatizing videos of Alton Sterling’s killing were posted and dissected by activists on Twitter. No viewer can forget the FacebookLive real-time video Lavish Reynolds posted of the shooting death of her boyfriend Philando Castile.

Adjectives cannot capture the horror of these videos or the sickening feeling that results from witnessing the routine killing of Black people by agents of the state. But in addition to being nauseating, tragic, appalling, and graphic, they are something else: indispensable.

These videos leave no plausible deniability about the reality of being policed while Black in America. For too long, Black people have had complaints of abusive policing dismissed as being paranoid and exaggerated. These videos have served as bitter affirmation of long-expressed concerns. This stream of visual proof has contributed to a new civil rights movement for the 21st century. Black Lives Matter activists have added their invaluable voices to the crusade for racial justice and police accountability, their activism powered by hashtags and livestreams. As a result, we have begun to see some glimmers of change in policing policy. For example, the DOJ just issued a scathing report about racial bias in Baltimore’s policing, and announced a national initiative to track the number of killings at the hands of police.

In short, this revolution is in the televising.

Which is why the Korryn Gaines shooting should make us all stop and think about how it is televised. It is a stark reminder that each of the powerful images and videos that have lent fire to the movement for police accountability relied on a private company to make them public. Periscope, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube—you name it: They set the rules for publishing speech, and set norms for public debate. Social media companies enjoy power over our speech previously held only by government.

Unfortunately, they also censor a staggering amount of speech. The First Amendment generally does not constrain private companies as it does government, so our constitutional right of free speech offers little protection from digital censorship. And that matters.

In the Gaines case, it’s not exactly clear why Facebook granted law enforcement’s request: the company’s justification for this kind of account shut-off appears to be lumped into the vague category of “emergency disclosures.” Of course, shutting down an account is the opposite of disclosure. What if the officers who stopped and killed Philando Castile had made a request to shut down Ms. Reynolds’ live-feed? The public would have been deprived of a video of immense public concern and impact. For just this reason, the ACLU has been at the forefront of securing the First Amendment right to record police engaged in their public duties. Indeed, the ACLU promotes our own “Mobile Justice App” to help civilian journalists exercise their constitutional right to document police encounters. Social media companies eager to cooperate with law enforcement requests should not be permitted to veto that right.

We must be active consumers, and demand at least three things from our social media platforms in exchange for choosing their services: transparency, consistency, and due process. Our Northern California affiliate has put together a phenomenal guide to help social media companies to get these balances just right.

- Transparency. Companies must be very clear about what content they either turn over or take down at the request of law enforcement. As internet privacy activist Lauren Weinstein has written, customers deserve detailed, granular policies that put them on real notice about whether and when their speech can be silenced, hidden, or shared.

- Consistency. Broad company policies that permit interpretation and ad hoc application mean that censorship decisions are political. If social media companies are more likely to grant content takedown requests from law enforcement, that becomes a statement of position in the police accountability debate.

- Due process. You should have a right to know why your speech was censored—and to press an appeal if you think it’s wrong.

These principles are not just vital for preserving the role of speech in assuring justice and accountability, they’re good for the corporate bottom line. We all want a forum for our speech that doesn’t have a secret mute button. And if and when a secret mute button is pushed, social media companies need to know that this will affect their business—and understand that they are choosing a political role, intentionally or not, in the campaign to document and publicize government abuse.

The Gaines situation can serve a clarion call to companies to prepare for exactly this kind of situation—specifically and transparently—so that they don’t risk becoming glorified propaganda wings of the state.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.