This month marks 50 years since the landmark Supreme Court ruling that cemented students’ rights to free speech in public schools, Tinker v. Des Moines. We’re inspired to see that students still take advantage of their First Amendment rights and speak out on political issues today.

We grew up in Iowa, where our father was a Methodist minister. Believing that faith should be put into action, our parents involved all of us kids in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, and later with the Quakers. We never could have imagined that this family tradition of civic engagement would make us central players in one of the most consequential Supreme Court cases about students and free speech ever brought by the ACLU.

When we were teenagers in 1965, we started to see horrific news about the escalating war in Vietnam, thanks to the brave journalists reporting there. And we knew that young people in Des Moines were being to be sent to war, and some were coming home in coffins.

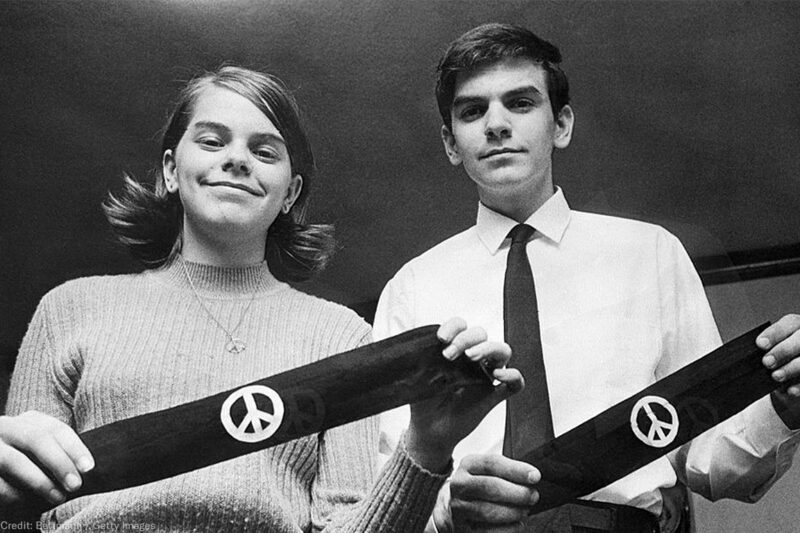

A small group of students wanted to do something about it. We decided to wear black armbands to school to send a message of mourning for the dead in Vietnam on both sides and support for a Christmas truce. The school suspended five of us for wearing the armbands.

%3Ciframe%20width%3D%22560%22%20height%3D%22315%22%20thumb%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.aclu.org%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fweb19-tinker-thumbnail-1160x315.png%22%20src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fembed%2Fgo63SCNT6OQ%3Fautoplay%3D1%26version%3D3%22%20frameborder%3D%220%22%20allow%3D%22accelerometer%3B%20autoplay%3B%20encrypted-media%3B%20gyroscope%3B%20picture-in-picture%22%20allowfullscreen%3D%22%22%3E%3C%2Fiframe%3E

Privacy statement. This embed will serve content from youtube.com.

The Iowa Civil Liberties Union said that was a violation of our First Amendment rights and told us to try to negotiate with the school board to change the policy. When the board voted to continue the ban on armbands, the national ACLU took the case to court on behalf of us and another student, Chris Eckhardt.

Dan Johnston, a young lawyer also from Des Moines and just out of law school, argued the case. After defeats at the lower courts, he won 7-2 at the Supreme Court on February 24, 1969. “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” the majority opinion said.

The court went on to affirm the freedom that young people have under the Constitution:

In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students… are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State. In our system, students may not be regarded as closed-circuit recipients of only that which the State chooses to communicate. They may not be confined to the expression of those sentiments that are officially approved. In the absence of a specific showing of constitutionally valid reasons to regulate their speech, students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views.

There are still limits on what students can do in public school. Students can’t “materially disrupt” the functioning of their school or “intrude upon the rights of others” — though what’s considered to meet those standards can depend on the situation.

Over the years, students have protested everything from apartheid in South Africa to a ban on dancing. Students with Black Lives Matter have inspired countless young people and adults by standing up for racial justice. And of course there were 2018’s massive student protests that followed the shooting massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Sometimes, the ACLU has had to get involved to make sure that schools respect student speech, successfully defending the right of students to wear an anti-abortion armband, a pro-LGBT T-shirt, and shirts critical of political figures. The ACLU has even defended the rights of high school students who wanted to protest the ACLU.

Social media has provided even more opportunities for students to make their voices heard — although some schools have attempted to extend their power to punish students for speaking off-campus and outside school hours.

Schools aren’t supposed to only teach things like math and science — they’re also supposed to prepare students to participate in society. The ability to speak out and make up your own mind through freedom of expression lies at the core of what it means to live in our society, and it wouldn’t make sense for public schools to try to stop students from learning to exercise their speech rights. A half century after the Supreme Court recognized that truth, it’s as important now as ever.

To mark the anniversary of the Supreme Court’s historic ruling, we’re travelling to Iowa for series of events including a livestream by Iowa Public TV on February 22. We’re being joined for part of it by journalism students and advisers from Parkland’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, who are collecting stories of how students are using their First Amendment rights as part of the Schoolhouse Gate Project.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.