Under This Law, Encouraging Undocumented Immigrants to Seek Shelter Could Be a Crime

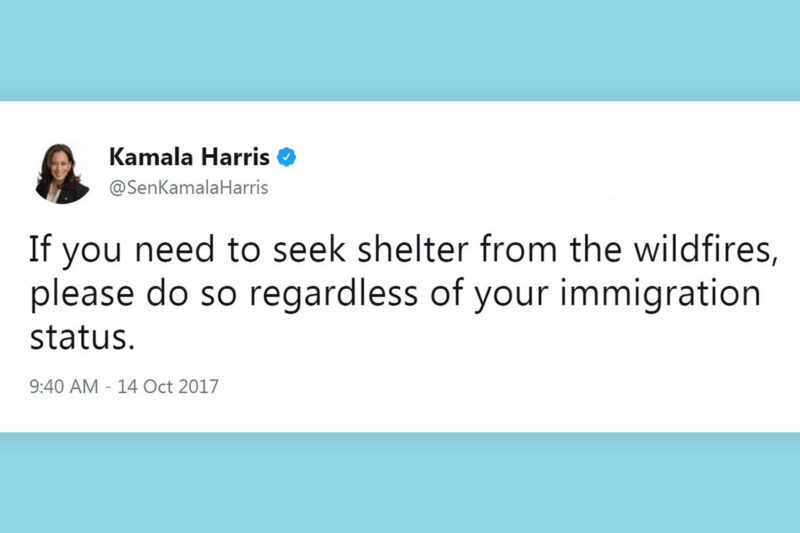

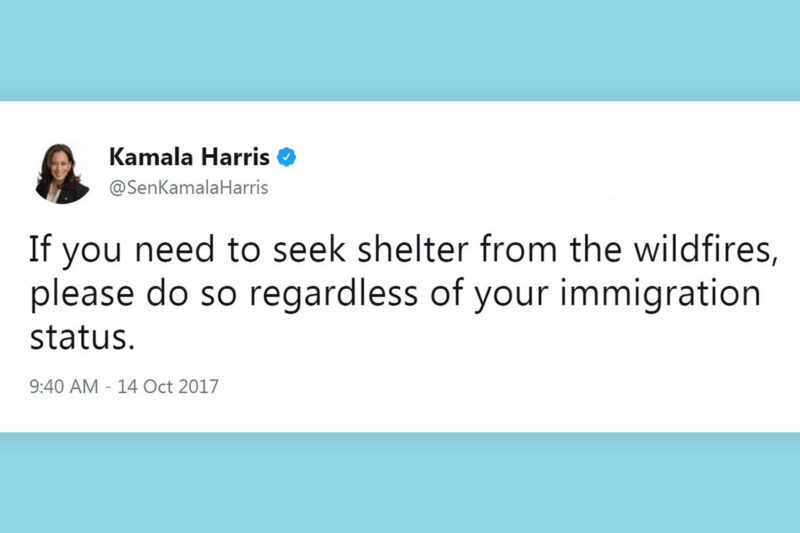

As wildfires raged across Northern California last week, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) took to Twitter to encourage those in need to seek shelter, even if they didn’t have lawful immigration status.

Senator Harris’s desire to protect all her constituents is admirable. It also may be a crime.

A section of the federal Immigration and Naturalization Act states that any person who “encourages or induces” a non-citizen to “come to, enter, or reside” in this country in violation of the law is guilty of a felony, and may be imprisoned for up to five years. For a person to be found guilty, the prosecution must show that the person knew or recklessly disregarded the fact that the non-citizen’s action was unlawful. Harris’s tweet arguably “encouraged” undocumented immigrants to “reside” in the country. That’s precisely the type of speech a zealous federal prosecutor could target for criminal sanction under this law.

Senator Harris is in good company. Other potential “criminals” include:

- A woman who tells her undocumented housekeeper that she should not depart the U.S. or else she won’t be allowed back in. (A former U.S. Customs and Border Protection official stood trial in just such a case.)

- A university president who publishes an op-ed arguing that DACA recipients should consider her campus to be a “sanctuary” after their deferred action expires.

- A community organization that announces its shelters and soup kitchens are open to homeless undocumented youth in their area.

This law clearly oversteps the First Amendment, which does not allow the government to criminalize these kinds of speech. The Supreme Court has stated clearly: “The mere tendency of speech to encourage unlawful acts is not a sufficient reason for banning it.” That’s why the ACLU yesterday submitted an amicus brief to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit arguing that this law is unconstitutional.

The government can only prohibit “unprotected” speech, like incitement to violence or speech that itself constitutes a crime, like harassment. Speech “encouraging” immigration violations does not qualify. This makes the law we challenged “presumptively unconstitutional,” because it regulates the content of things we can say.

The ACLU filed its brief in a criminal case against Evelyn Sineneng-Smith, an immigration consultant from San Jose, California. Ms. Sineneng-Smith was convicted in 2013 for filing labor applications for clients she knew were not eligible for green cards at the time. Despite the fact that all the information Ms. Sineneng-Smith filed was accurate — including disclosure of the fact that her clients had been in the country illegally for years — she was convicted of “encouraging or inducing” her clients to remain in the U.S. She has appealed her conviction.

Our brief argues that the First Amendment protects the right of an individual — whether Evelyn Sineneng-Smith or Sen. Kamala Harris — to speak their mind on this hotly debated, sensitive subject without fear of prosecution. This includes speaking with and advocating for undocumented individuals who must navigate the complex web of U.S. immigration law. With this anti-encouragement law on the books, the only sure way to avoid prosecution for such speech is self-censorship.

Now, as ever, immigration is an issue of enormous public concern and controversy, especially given the hostile stance of the Trump administration and some state officials toward immigrant communities. For those in our communities who are undocumented immigrants, or whose loved ones are undocumented immigrants, there is nothing more important than speaking on these issues. The last several months have demonstrated precisely how movements for immigrant justice rely on robust political speech: organizing rallies against deportation, speaking to undocumented people about how to avoid being separated from their families, and more.

Freedom of speech is at the foundation of these efforts, and we must strive to keep it that way.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.