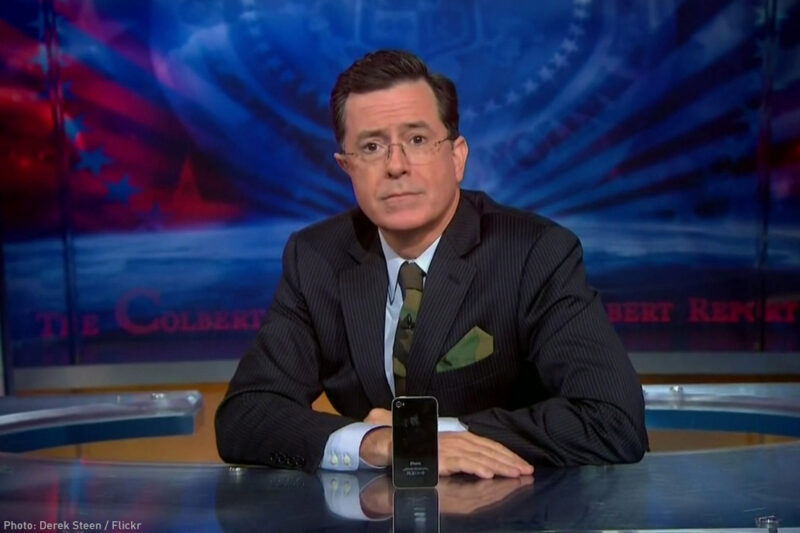

Stephen Colbert stirred controversy last Monday when he roasted President Donald Trump in his “Late Show” opening monologue. Parodying President Trump’s penchant for lame puns and bad one-liners — Trump recently referred to CBS’s “Face the Nation” as “Deface the Nation” — Colbert piled the burns on hot and fast:

“You’re the ‘presi-dunce,’ but you’re turning into a real ‘prick-tator.’ Sir, you attract more skinheads than free Rogaine. You have more people marching against you than cancer. You talk like a sign-language gorilla that got hit in the head. In fact, the only thing your mouth is good for is being Vladimir Putin’s cock holster.”

On Twitter, the hashtag #FireColbert started trending worldwide. A couple of days later, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai said that the agency was reviewing the incident after receiving numerous complaints from concerned viewers. He also indicated that fines could be levied against CBS for any violation of federal broadcast regulations.

The FCC will almost certainly stand down.

The agency’s standard operating procedures require it to conduct a review whenever it receives a complaint. And Colbert’s choice of phrase, offensive though it was, isn’t enough to merit punishment by the FCC. (If it were, many of the shows on cable and late-night television would be sanctionable.) To the contrary, federal law makes clear that network broadcasters cannot be punished for airing offensive, profane, or otherwise “indecent” content between the hours of 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. unless that content is also legally “obscene.”

%3Ciframe%20allowfullscreen%3D%22%22%20frameborder%3D%220%22%20height%3D%22384%22%20src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fembed%2FkyBH5oNQOS0%3Fautoplay%3D1%26version%3D3%22%20thumb%3D%22%2Ffiles%2Fweb17-georgecarlin-thumb-580x384.jpg%22%20width%3D%22580%22%3E%3C%2Fiframe%3E

Privacy statement. This embed will serve content from youtube.com.

In 1973, the Supreme Court established a three-part test for determining whether material qualifies as obscene. First, the material must appeal to the “prurient interest” (meaning it has to have the tendency to excite lustful thoughts). Second, the material must depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically identified by the regulating authority. Finally, taken as a whole, the material must lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

This is a stringent test, and rightly so. It’s meant to cover only certain forms of hardcore pornography while extending First Amendment protection to the sort of profanity you might find in James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” (No, seriously, it’s filthy.) Whatever you think about the propriety of Colbert’s language, it’s not obscene.

The strong First Amendment protections enjoyed by Stephen Colbert do not apply across the board, however. A very different standard allows the FCC to punish broadcasters for airing “indecent” material between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. That standard came out of a famous case, FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, decided nearly four decades ago, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the FCC could prohibit the airing of George Carlin’s famous monologue, “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” In light of the uniquely government-reliant and pervasive nature of broadcast media, the Supreme Court decided that the government has the authority to regulate broadcast television and radio to protect children and unwitting adults from indecent content at times they’re likely to be exposed to it — even if the content is not “obscene.”

Although the Supreme Court took pains to emphasize the “narrowness” of its decision, the FCC has repeatedly expanded the scope of its indecency regulations by adopting ever more vague and subjective standards. In 2005, the agency took the position that broadcasters could be punished for allowing even “fleeting indecency,” meaning non-scripted visual or verbal indecency during a live broadcast. (Take, for example, Janet Jackson’s famous wardrobe malfunction during the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show. The FCC fined CBS for the infraction, although its decision was ultimately reversed on procedural grounds.)

The FCC’s enforcement of its indecency regulations can most charitably be described as arbitrary. The agency fined PBS for broadcasting a Ken Burns’ documentary because it includes swears uttered by Black musicians. On the other hand, the FCC decided that the uninhibited use of profanity in “Saving Private Ryan” was acceptable because removing the expletives would “alter . . . the nature of the artistic work and diminish . . . the power, realism and immediacy of the film experience for viewers.”

That arbitrariness has led to self-censorship: Broadcasters have squelched important artistic and political speech in order to avoid government sanction. In just one example, PBS provided broadcasters with a version of the civil rights documentary “Eyes on the Prize” that edited James Forman’s call for a more aggressive approach to the civil rights movement: “If we can’t sit at the table, let’s knock the fucking legs off.”

It’s time to reconsider how we regulate broadcast media. Since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Pacifica, cable television, satellite radio, and the internet have allowed many people unfettered access to the whole scope of human creativity, including “indecent” content that would undoubtedly be regulated by the FCC if it were aired on broadcast television or radio. By the standards of modern media and political discourse, the Supreme Court’s concern over George Carlin’s seven dirty words seems downright quaint. We have a president who brags about grabbing women “by the pussy.” Meanwhile, the government claims the power to regulate whether people can discuss it on network television.

Millions of Americans, especially poor people and people of color, rely on broadcast television and radio as their primary sources for news and entertainment. Their First Amendment rights — in particular, the right to receive information free from government censorship — are being restricted by an outdated and arbitrary regulatory regime that accomplishes nothing except the sterilization of public discourse that takes place over broadcast media. Stephen Colbert is probably off the hook this time, but the FCC has no business policing what people say on television.