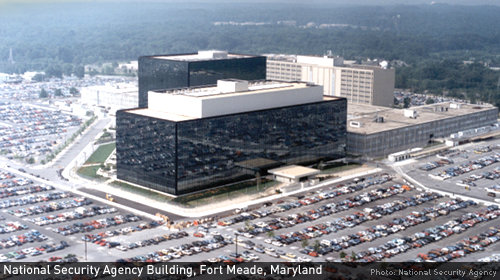

Today, in a hushed courtroom in Washington, D.C., not far from the now-empty halls of Congress, a federal appeals court heard arguments in Klayman v. Obama, a challenge to the NSA's bulk collection of telephone metadata first revealed by Edward Snowden. If you have ever made a phone call, or received a phone call, this case has implications for your personal privacy and you should pay close attention to what happens next.

The appeal follows a December win for Larry Klayman, a conservative lawyer and activist and the plaintiff in the case, where a district court judge ruled the program was likely unconstitutional. Today, government lawyers attempted to argue that this program should be allowed to continue.

The arguments hinged on a central question: Is the warrantless, non-targeted surveillance currently being conducted by the NSA, which is scooping up data on all (or almost all) calls made or received on U.S. telephone networks, a violation of the Fourth Amendment?

The government tried to argue that it is not. They claim that their searches of this massive call record database are reasonable, and that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in the numbers one dials.

But, as EFF Legal Director Cindy Cohn argued on behalf of both EFF and the ACLU as friends of the court, the government has no right to scoop up such a massive amount of personal information about Americans in the first place.

(To read the ACLU and EFF's amicus brief in Klayman v. Obama, click here.)

The truth is, the NSA's bulk collection of the phone records of all Americans is fundamentally different than putting a trace on the phone of an individual suspected of wrongdoing. The sheer scale of this program means that we are all suspects, or at least potential suspects, in the eyes of our government.

Think about the impact of knowing that your every phone interaction is being logged by the government. This kind of surveillance has even greater implications for lawyers and journalists, who have to worry about protecting the confidentiality of clients and sources. The phrase "chilling effect" seems insufficient to describe the potential loss to our society, to our whole way of life, as we slowly begin to censor ourselves because we know that the government is always monitoring our communications.

This is contrary to the very nature of a democracy, where people are supposed to hold their government to account. Who will be willing to speak out against an abusive government when that government knows all our deepest, darkest secrets?

Governments are by nature interested in acquiring more power, and today, more than ever, information is power. We should not be surprised that the government wants to know who Americans are speaking with, and for how long, and how often. We rely on the Constitution, and on the other branches of government, to provide a check on that desire.

Today, we asked the court to provide that check and to declare bulk collection of American's telephone metadata unconstitutional.

The ACLU has also filed its own challenge to the constitutionality of this program, ACLU v. Clapper. An appeals court decision is pending in that case.

Learn more about government surveillance and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.