New Documents Show This TSA Program Blamed for Profiling Is Unscientific and Unreliable — But Still It Continues

Yawning. Whistling. Being distracted. Arriving late for a flight.

Are people who do these things at the airport showing signs of deception? The Transportation Security Administration apparently thinks so. Thousands of TSA officers use so-called “behavior detection” techniques to scrutinize travelers for these and scores of other behaviors that the TSA calls signs of deception or “mal-intent.” The officers then flag certain people for additional screening and questioning.

But documents the ACLU has obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit show that the TSA itself has plenty of material showing that such techniques are not grounded in valid science — and they create an unacceptable risk of racial and religious profiling. Indeed, TSA officers themselves have said that the program has been used to do just that.

We got more than 13,000 pages of documents from the TSA, and today we’re releasing a report on what we found. In the past, government auditors, members of Congress from both parties, and independent experts have labeled the program wasteful and ineffective. Our study reinforces these conclusions, and more.

Here are the top five things we learned from the TSA’s documents:

1. Studies in the TSA’s own files reinforce that the TSA’s use of behavior detection is unscientific and unreliable.

The TSA turned over numerous academic and scientific research studies. Instead of supporting the program, the literature directly undercuts the notion that officers can detect deceit or bad intentions based on people’s behavior with any reliability, especially in a place like the airport.

The social science literature in the TSA’s files even includes specific findings that behaviors people commonly associate with lying — gaze aversion, nervous or fidgety gestures, or placement of hands over the mouth — are not reliable cues to deception. But the TSA’s secret list of indicators includes those very behaviors, along with others for which there is no empirical support.

These documents suggest that the TSA has persisted in maintaining a behavior detection program that is at odds with the scientific studies in its own files.

2. The TSA broadened the behavior detection program and its surveillance techniques.

In 2009, the TSA expanded the program beyond security checkpoints at airports, enabling “behavior detection officers” — some of them in plain clothes — to “spread throughout the entire airport” and surveil travelers covertly. Officers use “casual conversation” to draw out information from passengers — a technique that appears less like conversation and more like stealth interrogation.

These techniques are troubling because travelers likely will assume that they may not simply ignore officers who converse with them. And various behavioral “indicators” (revealed in documents leaked to The Intercept in 2015) —“gives non-answers,” “lacking details about purpose of trip,” “downplaying of significant facts when answering questions” — show how avoiding contact with behavior detection officers can be construed as an indicator itself.

%3Ciframe%20allowfullscreen%3D%22%22%20frameborder%3D%220%22%20height%3D%22326%22%20src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fembed%2FNiUwwemwpok%3Fautoplay%3D1%26version%3D3%22%20thumb%3D%22%2Ffiles%2Fweb17-spot-video-580x326.jpg%22%20width%3D%22580%22%3E%3C%2Fiframe%3E

Privacy statement. This embed will serve content from youtube.com.

3. The TSA overstated the scientific validity of behavior detection techniques in communications with Congress.

TSA officials have repeatedly assured members of Congress that the behavior detection program uses “objective criteria” and is “supported by leading experts in the field of behavioral science and law enforcement.” Those statements, however, ignored or misconstrued the body of empirical research in the TSA’s files (or otherwise publicly available) that indicated otherwise.

4. Materials in the TSA’s possession raise questions about possible anti-Muslim bias at the TSA.

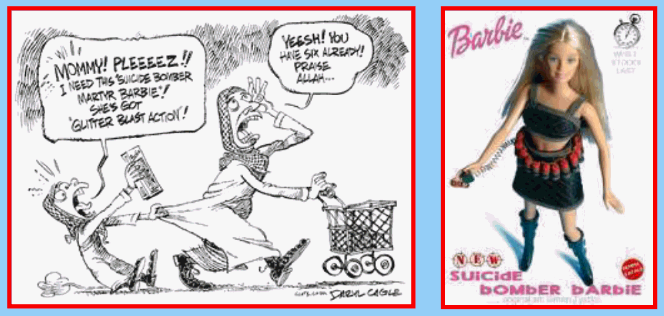

Various documents from the TSA’s files reflect a disproportionate focus on or an overt bias against Arabs, Muslims, and people of Middle Eastern or South Asian descent. For instance, until late 2012, training materials for behavior detection officers focused exclusively on examples of Arab or Muslim terrorists, and a TSA-authored presentation titled “Femme Fatale: Female Suicide Bombers” reflects demeaning stereotypes about Muslims and women, including these images:

It is unclear whether and how these materials factored into the TSA’s behavior detection program, but they do not provide empirical or scientific support for behavior detection methods, and their existence in the TSA’s records raises concerns about potential bias in TSA programs.

5. The TSA’s documents reveal details of specific instances of racial or religious profiling.

The TSA produced records of investigations into alleged profiling by behavior detection officers in Newark, Chicago, Miami, and Honolulu. Those records highlight the ease with which behavioral indicators can be used as a pretext for harassing minorities and disfavored groups. They also show that some officers refer passengers for additional screening far more often than others — a troubling indication that the TSA’s “indicators” are subjective and arbitrary.

Based on the documents, our report includes several recommendations: First, the TSA should phase out the behavior detection program. The available information shows that the program lacks scientific support and threatens civil liberties.

The agency should also implement a rigorous anti-discrimination training program for all TSA employees.

Congress should use its oversight role to make sure that these changes happen. Given the anti-Muslim policies coming from the Trump administration, the TSA should not be allowed to retain a program that can be used as a cover for racial and religious profiling.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.