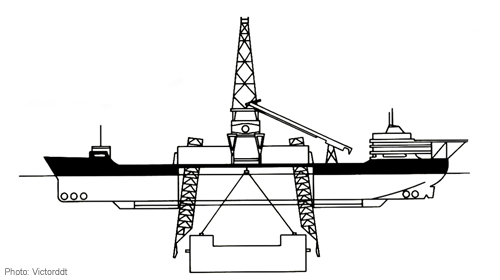

It is the height of the Cold War. A nuclear-missile-equipped Soviet submarine sinks in the Pacific Ocean, in suspicious circumstances. The CIA commissions reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes to secretly build a massive ship capable of lifting the submarine off the ocean floor using a colossal extendable claw. The ship is built, christened the "Glomar Explorer," and — disguised as a deep-sea mining vessel — sent on a top-secret recovery mission. Out on the high seas, the Glomar's claw locks onto the sub and raises it toward the surface — until it breaks into pieces with the crew watching helplessly. The crew recovers only a portion of it, the entombed bodies of Russian seamen still inside.

Soon, intrepid journalists get wind of the operation and file Freedom of Information Act requests for more information. A CIA lawyer — operating under the cover name Walt Logan — thinks up a novel way to keep the mission secret without telling an all-out lie: refuse to confirm or deny whether records about the Glomar Explorer's mission exist. One journalist sues over this confusing non-response, and a battle over government secrecy follows in court.

This is not the plot of a new Hollywood thriller. It is the true story of the origin of what is now known as the "Glomar response," recently presented in a fascinating Radiolab podcast featuring the ACLU's Jameel Jaffer. It is well worth a listen.

Why should we care? It's not just because we all like a good tale of intrigue at sea; it's because the CIA and other government agencies continue to use the Glomar response to facilitate excessive government secrecy when Americans seek records under the Freedom of Information Act. Building off that first episode of Cold War concealment four decades ago, in answer to requests by the ACLU and others, the government has refused to confirm or deny whether it has records about drone strikes, the targeted killing of U.S. citizens, secret detention and abuse of prisoners at the U.S. airbase in Bagram, Afghanistan, NSA surveillance, and torture and rendition of detainees. These are all areas where the public has a vital interest in accurate information about the government's actions and abuses. By relying on the Glomar response, the government seeks not only to keep the public in the dark and cut off debate, but also to preempt efforts to get courts to order release of specific documents.

There are limited circumstances in which a Glomar response may be necessary to protect veritable government secrets, but as I've written before in The New York Times (with Jameel Jaffer) and in the NYU Law Review, it has been deployed far beyond acceptable bounds. Perhaps most disturbing is the way the government uses Glomar to facilitate selective and misleading disclosures. Government officials often "leak" information to the press that paints controversial programs in a positive light on the condition that the press withholds their names. But when asked to officially release records under FOIA, those officials clam up and hide behind the Glomar response. The result is an absurd double standard, and our democracy suffers for it.

As Radiolab's story illustrates, the Glomar response was spawned in the clandestine depths of Cold War spycraft. It has unfortunately grown to typify the duplicitous government secrecy of our modern age.

Learn more about government secrecy and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.