ACLU Challenges Computer Crimes Law That is Thwarting Research on Discrimination Online

UPDATE: On March 27, 2020, a federal court ruled that research aimed at uncovering whether online algorithms result in racial, gender, or other discrimination does not violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). The ruling in our case is a major victory for civil liberties and civil rights enforcement during the digital age.

In the digital age, with everyone experimenting with new uses of big data, algorithms, and machine-learning, it's crucial that researchers be able to engage in anti-discrimination testing online. But a federal computer crimes law, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, is creating a significant barrier to research and testing necessary to uncover online discrimination in everything from housing to employment. The ACLU filed a lawsuit today on behalf of a group of academic researchers, computer scientists, and journalists to remove the barrier posed by the CFAA’s overbroad criminal prohibitions.

Our plaintiffs want to investigate whether websites are discriminating, but they often can’t. Courts and prosecutors have interpreted a provision of the CFAA—one that prohibits individuals from “exceed[ing] authorized access” to a computer—to criminalize violations of websites’ “terms of service.” Terms of service are the rules that govern the relationship between a website and its user and often include, for example, prohibitions on providing false information, creating multiple accounts, or using automated methods of recording publicly available data (sometimes called “scraping”).

The problem is that those are the very methods that are necessary to test for discrimination on the internet, and the academics and journalists who want to use those methods for socially valuable research should not have to risk prosecution for using them. The CFAA violates the First Amendment because it limits everyone, including academics and journalists, from gathering the publicly available information necessary to understand and speak about online discrimination.

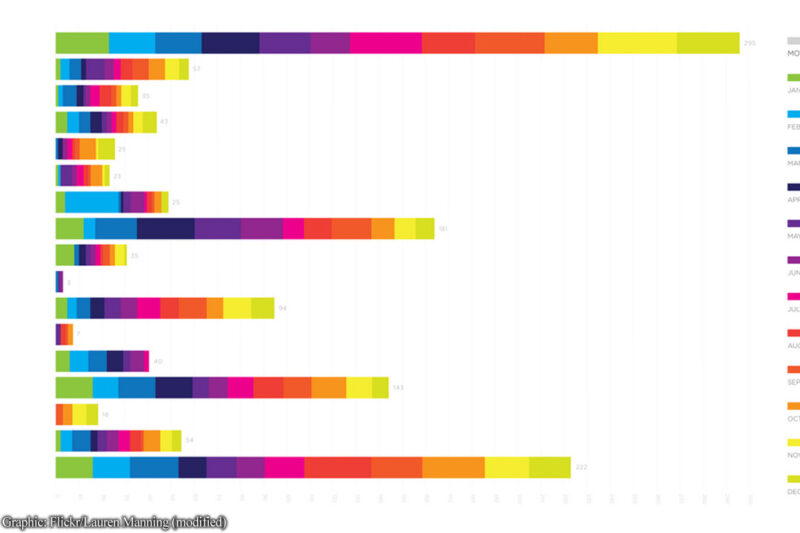

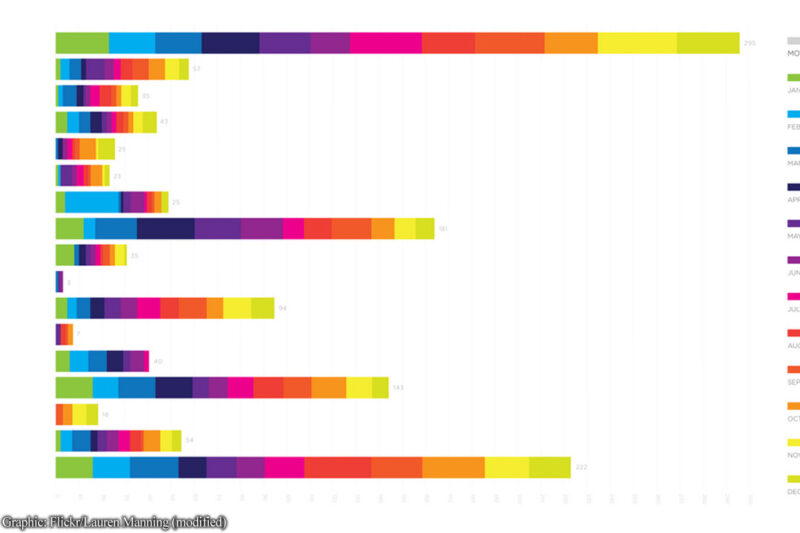

As more and more of our transactions move online, and with much of our internet behavior lacking anonymity, it becomes easier for companies to target ads and services to individuals based on their perceived race, gender, or sexual orientation. Companies employ sophisticated computer algorithms to analyze the massive amounts of data they have about internet users. This use of “big data” enables websites to steer individuals toward different homes or credit offers or jobs—and they may do so based on users’ membership in a group protected by civil rights laws. In one example, a Carnegie Mellon study found that Google ads were being displayed differently based on the perceived gender of the user: Men were more likely to see ads for high-paying jobs than women. In another, preliminary research by the Federal Trade Commission showed the potential for ads for loans and credit cards to be targeted based on proxies for race, such as income and geography.

This steering may be intentional or it may happen unintentionally, for example when machine-learning algorithms evolve in response to flawed data sets reflecting existing disparities in the distribution of homes or jobs. Even the White House has acknowledged that “discrimination may ‘be the inadvertent outcome of the way big data technologies are structured and used.’”

Companies should be checking their own algorithms to ensure they are not discriminating. But that alone is not enough. Private actors may not want to admit to practices that violate civil rights laws, trigger the negative press that can flow from findings of discrimination, or modify what they perceive to be profitable business tools. That’s why robust outside journalism, testing, and research is necessary. For decades, courts and Congress have encouraged audit testing in the offline world—for example, where pairs of individuals of different races attempt to secure housing and jobs and compare outcomes. This kind of audit testing is the best way to determine whether members of protected classes are experiencing discrimination in transactions covered by civil rights laws, and as a result it’s been distinguished from laws prohibiting theft or fraud.

Yet the CFAA perversely grants businesses that operate online the power to shut down this kind of testing of their practices. Even though terms of service are imposed by websites, whose interests may be adverse to anti-discrimination testing, the CFAA makes violating those terms a crime, even where there is no harm to a business. That means traditional, long-approved investigative techniques can’t be applied to the internet to ferret out insidious discrimination.

Much has been written about how problematic the CFAA is, including that it is so vague and broad as to cover everyday internet behavior (like lying on a dating profile or copy-and-pasting text from a website). It is also nearly impossible to comply with terms of service at all times, both because they’re so lengthy and because they can change at any time. Most users can’t realistically read them for every single website visited (each time they visit!).

Critically, the CFAA’s impact on academics and journalists threatens to limit our access to information of great public concern: what online discrimination looks like in the 21st century and what can be done about it.

There is no good reason to criminalize research into discrimination online. The CFAA harms not only our First Amendment freedoms, but our ability to keep up the fight for civil rights as our day-to-day habits and transactions move steadily online. Challenging this law in court today is the first step in this fight.

For more on the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, read our Speak Freely post, "Your Favorite Website Might Be Discriminating Against You."

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.