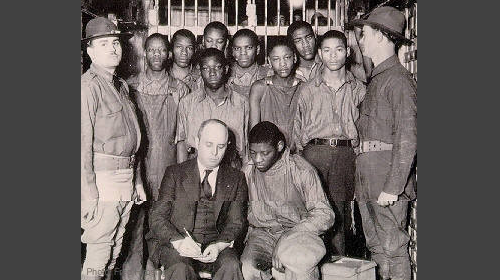

The Alabama Board of Pardons and Parole's posthumous pardon today of the last of the black men wrongly convicted of the rape of two white women 82 years ago in Scottsboro, Alabama seems to write the final chapter of a sorry story that epitomizes the racial injustice and procedural unfairness that dominated the criminal justice system in the United States in the beginning of the last century. It would be difficult to concoct a process more unfair from beginning to end. Starting with the arrest of nine black men and boys on fabricated and completely contradictory allegations of the rape of two white women, the case proceeded through a serious of rushed and unfair trials. The defendants were represented by counsel wholly unfamiliar with criminal defense work and unable to conduct even the most basic investigations. The jury deciding the case completely excluded African Americans and their deliberations were conducted under the very real threat of the lynching of the defendants. Although the alleged victims ultimately recanted their stories and admitted that their allegations of rape were complete fabrications, all of the men were convicted and all but one sentenced to death. During the case seemingly every ugly stereotype appeared, from the depiction of the criminally rapacious black male intent on ravishing white women to the attacks on the counsel who ultimately took on the case on remand as meddling communistic Jewish lawyers from New York.

But is this long overdue pardon the final word in one of the most sordid parts of our nation's history? It is certainly true that through the efforts of advocates including Walter Pollak, the ACLU lawyer who argued the case in the United States Supreme Court, the first steps were made toward requiring representation in capital, and later all criminal cases. The case also questioned the practice of categorical exclusion of people from juries on the basis of race. And the chilling images of thousands of people, including whole families, gleefully observing public lynching of African Americans have been relegated to the past.

But the troubling perceptions linking people of color, particularly African Americans and more particularly black males, to criminality have persisted. The fearful consequences of this link also continue. They can be life threatening as we see in the too frequent events of people of color killed after shopping for snacks or while seeking assistance after traffic accidents. And, even when the consequences are not fatal, when individuals of color are detained under suspicion of shoplifting after legitimate purchases at expensive stores or subjected to repeated stops on the streets while they are violating no laws, there seem to be no end to the reminders that a whole range of humiliating, degrading and potentially fatal actions are still taken by people convinced that race and ethnicity are sure signs of criminality.

The nine black men and boys unfairly charged with crimes 80 years ago are beyond continued suffering from the discrimination inflicted on them in their lifetime. They are likewise beyond the relief afforded by pardons. The clearing of their names does have symbolic importance, but the greatest tribute to their suffering would be for the nation to take an unflinching look at the way that race still informs too many aspects of our criminal justice system and take the steps necessary to give full meaning to our professed belief in equality before the law.

Learn more about racial profiling and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.