Texas Courts Rely on 'Of Mice and Men' to Define Intellectual Disability and Sentence People to Death

This piece originally appeared at Salon.

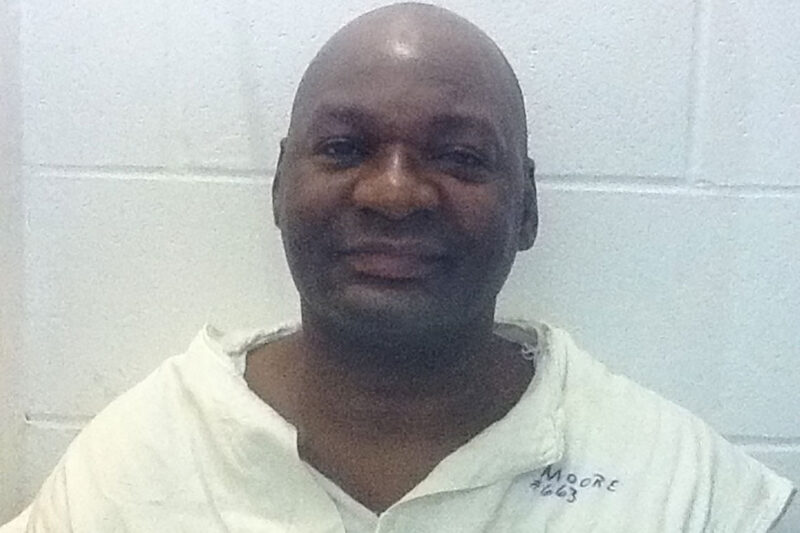

Bobby James Moore has a lifelong intellectual disability, yet he sits on Texas’s death row because the courts there used John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” to decide his fate.

That’s right—the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals went with a fictional novel over science and medicine to measure Bobby’s severe mental limitations. The justices heard a vast body of evidence demonstrating these limitations, which meet the widely accepted scientific standards for defining intellectual disability. Then they rejected it all according to seven wildly unscientific factors for measuring intellectual disability, drawn in large part from the fictional character Lennie Small. Bobby was no Lennie, they concluded, ruling that his disability wasn’t extreme enough to exempt him from the death penalty. On Friday, the Supreme Court will decide whether to take Bobby’s case.

Executing people with intellectual disabilities is unconstitutional. The grey area is that the Supreme Court allows the states to define intellectual disability, leaving an opening for Texas to create a standard based partly on “Of Mice and Men.” With its decision in Hall v. Florida two years ago, though, the Supreme Court made clear that states may not adopt definitions of intellectual disability that don’t conform to accepted scientific standards. It’s hard to come up with a less scientific standard than a novel written nearly 80 years ago. No one’s life should depend on an interpretation of Steinbeck.

Under current professional standards, a person with intellectual disability has significant deficits in intellectual functioning (IQ) and significant deficits in adaptive functioning (how well one adjusts to daily life) that manifest before the age of 18. Bobby has a clear intellectual disability that has been evident his entire life. Living in Houston in the 1970s, Bobby’s family was so poor that they often went without food. Bobby and his siblings found discarded food in the neighbors’ trash cans. When they got sick from the scraps, Bobby’s siblings stopped eating from the trash cans, but Bobby never learned that lesson. He would eat the discarded food and get sick, over and over again.

Growing up, Bobby rarely spoke. His teachers suspected that he had an intellectual disability, but they did not know what to do with him. They would ask Bobby to sit and draw pictures while they taught the rest of the class reading, writing, and math — or worse, they would send him to the hallway to sit alone. Bobby failed the first grade twice but was socially promoted to second grade. His abusive and alcoholic father slammed the door in the face of the few teachers who tried to intervene on Bobby’s behalf.

When he reached age 13, Bobby still didn’t know the days of the week, the months of the year, the seasons, or how to tell time. The school system finally acknowledged that Bobby should receive some intervention, and counselors recommended that his teachers drill him daily on this basic information. But by that point it was too late. The schools continued to socially promote him until he dropped out of school in the ninth grade.

Without support for his disability and in an effort to escape his violent home life, Bobby was left to survive on the streets. He got caught up with the wrong crowd, and at 20 years old, he followed two acquaintances who had made plans to rob a store. Bobby was armed with a shotgun, though the group just wanted money and had no intention to kill anyone. But Bobby panicked when an employee screamed, and he accidentally discharged the shotgun. He did not learn until later that his shotgun blast had hit a clerk.

Bobby was charged with homicide in 1980 and sentenced to death later that same year. He and his lawyers didn’t have a chance to present evidence of his intellectual disability until more than 20 years later, when the Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that the Constitution forbids the execution of people with intellectual disability. Bobby’s attorneys then petitioned for a hearing to show that he should be exempt from the death penalty.

They presented evidence from multiple experts and decades of records showing Bobby’s intellectual disability. Over the years, his IQ scores have ranged from the low 50s to the 70s, with an average score of 70.66. Using the appropriate scientific standards, the judge found that Bobby met the current definition of intellectual disability and should be sentenced instead to life without parole.

But the state appealed. That’s when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals used its unscientific factors, roughly based on Lennie, to uphold Bobby’s death sentence. The court ignored the Supreme Court’s ruling in Hall that determining intellectual disability should never be subject to a strict 70-point cutoff. In fact, when the state’s own expert tested Bobby, he scored 57.

Lennie Smalls was never meant to appear in court. He is a figment of John Steinbeck’s imagination. Texas must stop using such unscientific factors as an excuse to execute people with intellectual disability who don’t fit Lennie’s mold. The Supreme Court must give Bobby a chance to live.