Just Another Day at the Office

As a kid in growing up Queens in the 1950s, I dreamed of becoming a constitutional cop, a progressive Eliot Ness swinging a potent nightstick shaped like the Bill of Rights. I was lucky enough to live that dream, minus the nightstick, during 12 tumultuous years as an ACLU lawyer, culminating as national legal director during the presidency of Ronald Reagan.

My journey began in 1967 as a staff lawyer at the New York Civil Liberties Union. The late 60s and early 70s was an astonishing time to be a young ACLU lawyer. The Warren Court had just finished running a master class in reading the Constitution from the bottom up instead of the top down. Brown v. Board of Education had ignited the Equal Protection Clause. The excesses of McCarthyism had spurred a rejuvenated vision of free speech.

But that’s not even the half of it.

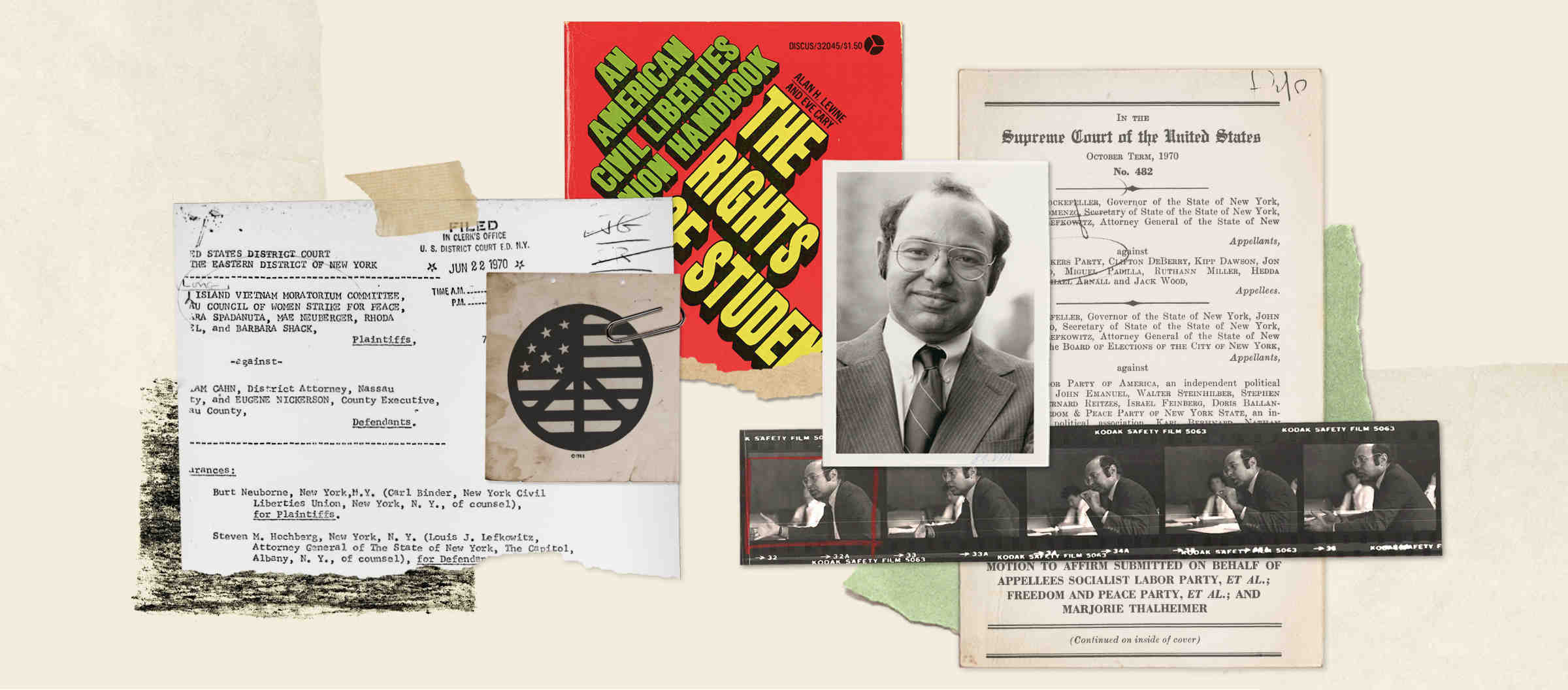

Former ACLU Legal Director Burt Neuborne, 1982

Lawrence Frank

Twenty unbroken years of Democratic control of the presidency (1932-52), followed by eight years of moderate Republican control (1952-60), and the eight Kennedy/Johnson years (1960-68) had salted the federal judiciary from top to bottom with a brilliant array of judges open to novel civil liberties arguments. The civil rights and anti-Vietnam movements provided day-to-day examples of the power of mass demonstrations. Baker v. Carr, a seminal case on redistricting, had signaled the Supreme Court’s readiness to rewrite the law of democracy. The ACLU itself was evolving from a small group of elite volunteers meeting in cramped quarters on the upper west side of Manhattan into a nationwide force for the enforcement of the Constitution.

The legal staff at the NYCLU back then included Paul Chevigny, fresh from establishing one of the nation’s first Legal Services offices in Harlem; Alan Levine, a passionate innovator unafraid to launch new arguments in defense of the weak; Bruce Ennis, the lawyer who forced the closing of Dickensian mental institutions, like the notorious Willowbrook State School; Eve Cary, a ground-breaking feminist lawyer who began at the NYCLU as a secretary and ended as one of our most beloved leaders; Art Eisenberg, who joined us after escaping from a graduate program in history; and me, liberated from three years as a Wall Street tax lawyer. Aryeh Neier, as executive director, and Ira Glasser, as associate director, filled out the extraordinary staff.

We all believed we could change New York, hell, America for the better by bringing the most vulnerable and marginalized groups under the Constitution’s protection. And I’d like to believe we did just that. But when I think about those heady, idealistic days, two stories truly exemplify what it was like to be a young civil liberties lawyer who believed he could right the wrongs of his hometown.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Hitting for the Constitutional Cycle

Lunch at the NYCLU in those days was a freewheeling intellectual adventure. One sunny November afternoon, over hero sandwiches at the joint on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 20th Street, Alan Levine was grumbling about a state judge’s refusal to require a due process hearing before a student activist was suspended. Bruce Ennis chimed in, insisting that folks confined to mental institutions had it even worse. Eve Cary complained about the awful conditions in women’s prisons. Not to be outdone, I bemoaned how hard it was to protect draft resistors and anti-Vietnam folks in the military.

And then it dawned on us: We were all running into the same legal stone wall. All of us confronted the existence of closed physical settings — schools, prisons, mental institutions, and the military — where the Constitution did not yet apply.

Over lunch, we sketched what came to be known as “the enclave theory” on the back of a napkin. We vowed to cooperate in a coordinated litigation program designed to bust open these black boxes and let the Constitution shine in. That promise launched the students’ rights movement, the prisoners’ rights program, the mental health project, and the defense of free speech in the military. And that was before dessert.

It’s hard to imagine the joyous intensity of our work. But one day in particular stands out. On Nov. 9, 1970, I hit for the constitutional cycle, arguing four constitutional cases at every level of the American judiciary on the same head-spinning day. I don’t think anyone else has ever been crazy enough — or lucky enough — to do it.

Thurgood Marshall, 1967

National Archives, Flickr

My day began at 9 a.m. in Justice Thurgood Marshall's Supreme Court chambers in Washington, D.C. I had taken the 6 a.m. Eastern shuttle to Washington in response to a telephone summons from the justice’s chambers the day before. Justice Marshall wanted to hear oral argument in chambers on an issue in Socialist Workers Party v. Rockefeller, a NYCLU case challenging a New York statute restricting access to the ballot by third parties.

In those years, New York required a third-party candidate to gather a fixed number of signatures in each of New York’s 62 counties in order to appear on the statewide ballot. The requirement forced leftist parties like the Socialist Workers Party or the Socialist Labor Party to send folks into sparsely populated upstate rural counties in the dead of winter looking for enough Marxist farmers willing to sign nominating petitions for candidates of the urban proletariat. I argued that requiring a fixed number of signatures in each of 62 counties with widely varying populations violated the one-person, one-vote principle enunciated in Baker v. Carr. A three-judge federal district court had invalidated the law, and the Supreme Court was considering New York’s appeal.

Justice Marshall wanted to ask the lawyers questions about the parties’ legal arguments and receive an oral report on the impact of having allowed the Socialist parties on the ballot for the November 1970 election. The truth is that very few voters had noticed. A month or so later, after being briefed by Justice Marshall, the full court voted 6-3 to summarily affirm the lower court’s finding of unconstitutionality.

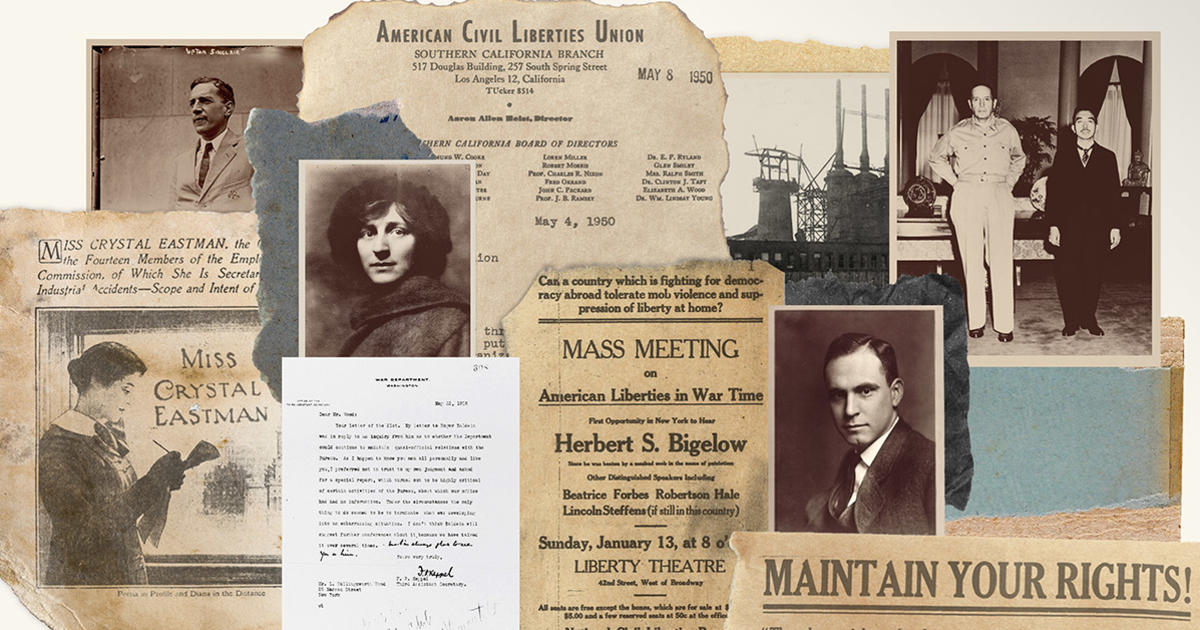

Image from an exhibit in the case mentioned.

I left Justice Marshall’s chambers and caught the Eastern shuttle back to New York. (It cost $12 in those days). At 2 p.m., I argued a First Amendment challenge to New York’s flag desecration statute before a three-judge panel in the elegant courtroom of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. I was representing opponents of the war in Vietnam who were being threatened with arrest by the Nassau County district attorney for displaying decals on their cars in the form of an American flag with a peace symbol superimposed. The DA called it unlawful flag desecration. The argument had been scheduled for 10 a.m., but the judges graciously rescheduled it to allow me to appear before Justice Marshall. Six weeks after the oral argument on Nov. 9, the Second Circuit declared the New York statute unconstitutional.

Once oral argument had ended on the flag desecration issue, I took the A train to the federal courthouse in Brooklyn for a 4:30 p.m. conference in Chief Judge Jack Mishler’s courtroom on an arcane procedural issue in Rosario v. Rockefeller, an NYCLU case challenging New York’s restrictive rules for voting in primary elections.

I won the procedural point, and the district court eventually declared the statute unconstitutional, but I eventually lost the Supreme Court appeal 5-4 in 1973.

It was almost 6 p.m. when I left Chief Judge Mishler’s chambers after completing the triple, arguing in the Supreme Court, the Second Circuit, and the Eastern District of New York on the same day. Then I cheated. With the fit upon me and hitting for the full four-level constitutional cycle in my grasp, I walked across the street to the Brooklyn criminal courthouse and asked a friendly Legal Aid lawyer to let me argue a couple of routine night court Eighth Amendment bail applications. Bail was granted in both cases. At 9 p.m., I ran out of clients, courtrooms, and gas.

Just another 15-hour day at the NYCLU office.

“What the hell did they teach you up there?”

I tried my first federal case in May 1968 before one of the smartest judges I’ve ever met — Jack Weinstein, fresh from his classroom at Columbia Law School.

Trying to integrate New York City’s public schools in those days was a daunting challenge. Racially segregated residential patterns, white-flight from the public schools, and years of racially motivated school zoning decisions had resulted in a public-school system that was as racially segregated as anything I had seen in the South. When well-meaning school officials sought to integrate previously all white schools, they were often met with massive white resistance. One particularly ugly resegregation technique was to integrate a school on paper and then use the truancy laws to expel the bulk of the newly admitted Black students.

Judge Jack B. Weinstein

AP

Confronted with an egregious misuse of the truancy laws to expel newly assigned Black students at Franklin K. Lane High School on the Brooklyn-Queens border, I went to Brooklyn federal court seeking reinstatement of the Black students. I filed a federal complaint alleging a violation of Brown v. Board of Education, arguing that New York City’s constitutional duty was to bring absent Black students back into the schools, not find ways to throw them out.

Since officials at the Board of Education expressed interest in taking the students back, I concentrated initially in trying to negotiate a mutually acceptable solution. When discussions with the Board of Education dragged on inconclusively for several weeks, Judge Weinstein, to whom the case had been assigned, lost patience and called my home late on a Thursday evening. Weinstein asked if I was the lawyer in the Franklin K. Lane case. I answered, “Yes,” expecting a request for information about the state of the negotiations. Instead, Weinstein asked me brusquely where I had gone to law school.

When I told him that I had graduated from Harvard, Weinstein snorted: “What the hell did they teach you up there?”

Actually, one of the things I had been taught was to try to settle cases before litigating them, but I was afraid to tell that to Weinstein, who was fully warmed up and busy berating me for letting my clients down.

“Don’t you understand,” he barked, “that you are their only lifeline to justice.”

He then inquired sarcastically when I might be ready for a court hearing. I gulped and asked whether 9 a.m. the next morning was okay; he gave me until Monday.

Trying a case before Jack Weinstein was like having a conversation with Radar in M*A*S*H. The judge conducted a running dialogue with himself, raising an evidentiary objection, and then ruling on it without bothering to wait for the slow-witted lawyers who were merely taking up space in his courtroom. After an intense, week-long trial, I expected a failing grade, not a verdict. When Weinstein ruled that the Black students were to be reinstated, I sheepishly confessed that since I had waited so long to seek the court order, the kids would need special tutoring to make up for the lost time.

Weinstein frowned and signed an order requiring the compensatory tutoring. A couple of days later, I asked that the tutoring be extended into the summer vacation to make certain that the students would not be left back. Weinstein nodded and signed the order. The next week, I explained that many of the kids had summer jobs that would conflict with the tutoring. I asked whether the city could be ordered to pay the students for attending the tutoring sessions. This time, Weinstein grinned and signed the order.

Two days later, when I showed up in his courtroom again, Judge Weinstein laughed: “Are you back here again?” “Wait a minute” he said, “I have just what you need.” He went back into chambers, and reappeared a minute later with a handwritten order stating: “Social injustice is hereby abolished in the United States. JBW.”

“Take it,” he said, “and don’t come back. You’ve graduated.”

Burt Neuborne is the Norman Dorsen Professor of Civil Liberties at NYU Law School. He spent 11 years on the ACLU legal staff, beginning in 1967 as a staff counsel at NYCLU, and serving from 1981-86 as ACLU National Legal Director. In 1995, he co-founded the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU and served as its founding legal director until 2007. His new book, "When at Times the Mob is Swayed" (The New Press 2019), asks whether American institutions are strong enough to withstand Trumpist appeals to divisiveness, xenophobia, and misogyny.