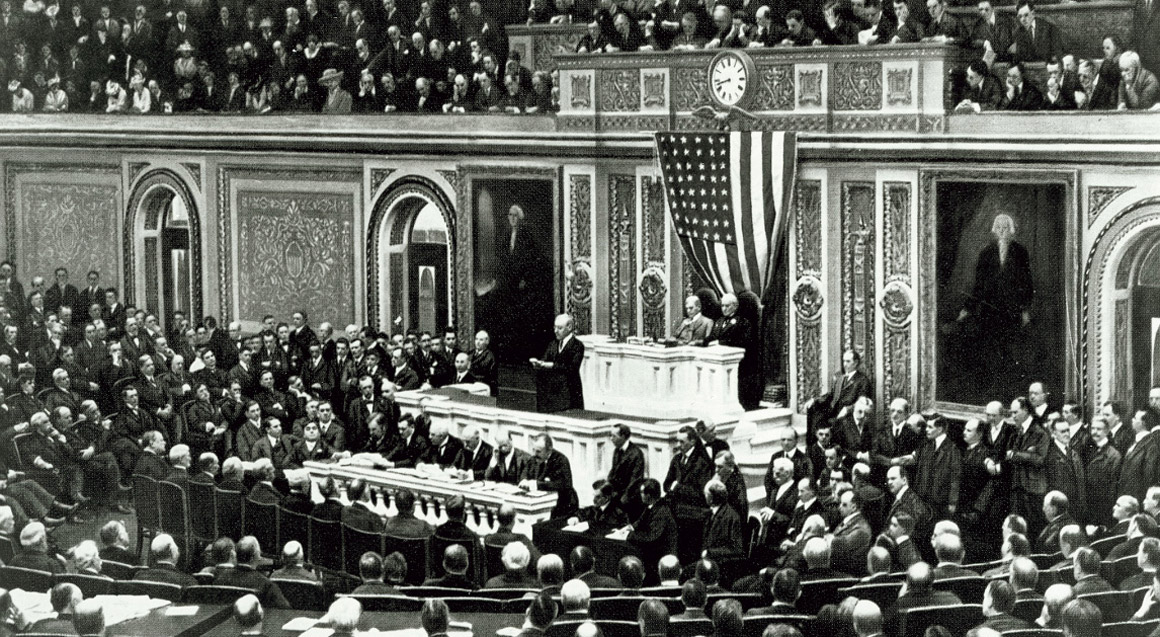

Following Wilson’s speech and Congress’ declaration of war, Eastman and Baldwin worked in a crisis atmosphere, filled with uncertainty and fear, but also a good measure of confidence. They knew something new and terrifying was happening to the country they loved. The pre-war congressional debates over possible federal censorship of ideas were truly frightening. They undoubtedly knew about the 1798 Sedition Act crisis under President John Adams from their history classes, but they sensed (quite accurately, it turned out) that something far more serious was likely to happen.

Some people joined the small AUAM-CLB orbit because they were angry at what was already happening. In June, Albert DeSilver, a wealthy attorney who quit his law firm to work with the CLB, declared “my law-abiding neck gets very warm under its ‘law-abiding collar these days at the extraordinary violations of fundamental laws which are being put over.”

And while the AUAM “office” consisted of just the two of them, and with no time for much planning, Eastman and Baldwin still felt up to the challenge.

And with good reason.