Crystal Eastman, the ACLU’s Underappreciated Founding Mother

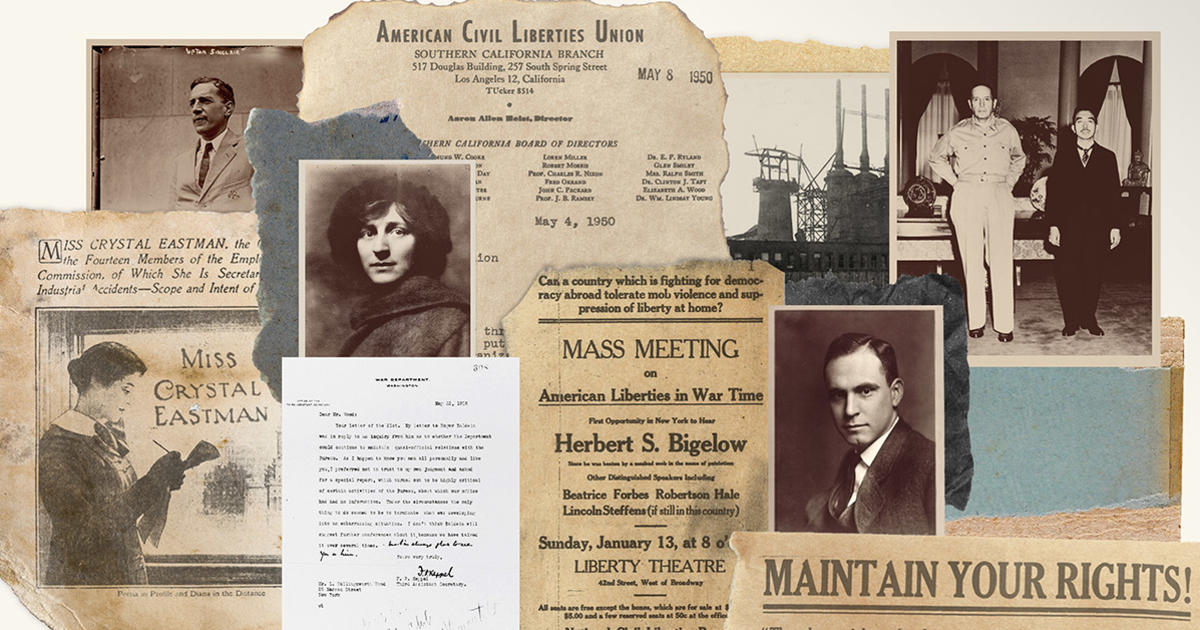

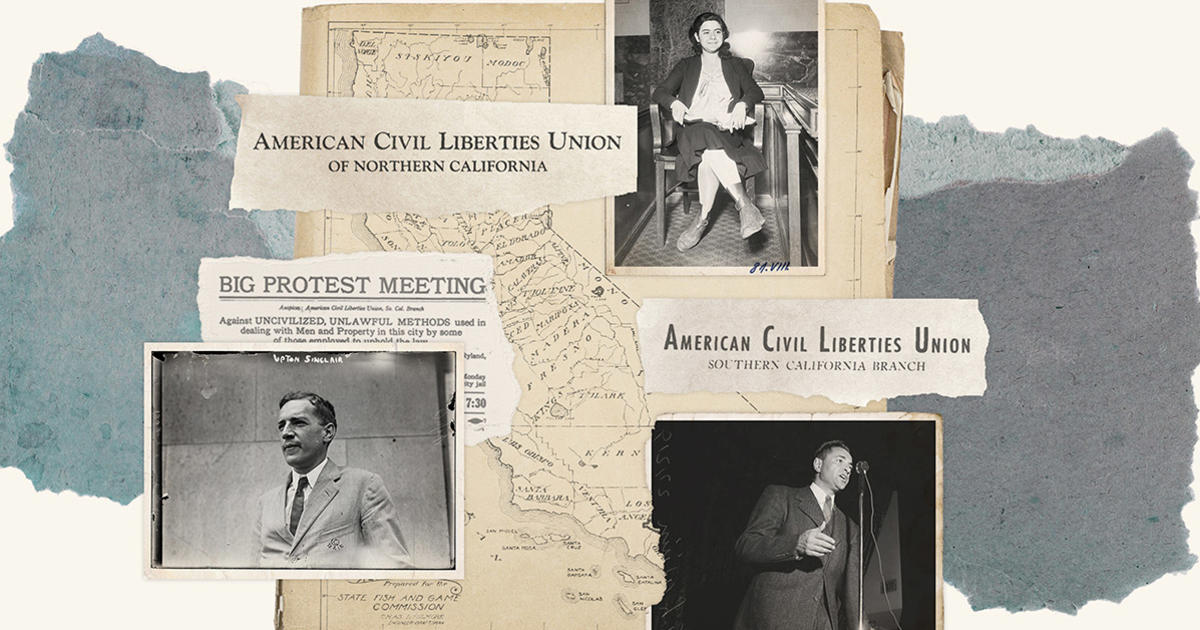

The year the American Civil Liberties Union was founded — 1920 — was also the year American women finally got the right to vote. This wasn’t mere coincidence. From the very beginning, the ACLU counted among its founders, organizers, and supporters an impressive roster of women, many of whom were veterans of the fight for suffrage.

One of these women, Crystal Eastman, is aptly credited as the ACLU’s founding mother: She co-founded and served as the director of the American Union Against Militarism and then generated the idea for that organization’s National Civil Liberties Bureau, which became the ACLU. Yet few people know her as a preeminent champion of most of the major movements for social change in the early 20th century — not just civil liberties but women’s suffrage and rights, pacifism, internationalism, and socialism — who frequently created and led multiple organizations simultaneously.

1920 was a watershed year for Crystal Eastman for many reasons. An active organizer for women’s suffrage, Eastman was unusual in not wanting to declare victory when the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. In a celebrated 1920 speech, “Now We Can Begin,” she set out to persuade resistant suffragist groups that their true goal should be not only equal suffrage but equal rights for women. An ardent pacifist, she continued her battle against World War I-era militarism and its byproducts, including intolerance of dissident speech and conscientious objectors; xenophobia; and the arrest and deportation of immigrants. As an idealistic socialist — one commentator remarked that Eastman was usually the only feminist in socialist circles and the only socialist in feminist circles — she studied and wrote about socialist revolutions around the world. And as a result of the Red Scare of 1919-20, she found herself on a black list and had a hard time finding paying work.

Crystal Eastman

National Woman’s Party, Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, Washington, DC

Once the ACLU was institutionalized, she ceded leadership of the organization to Roger Baldwin, her NCLB colleague who became the ACLU’s first director. ACLU annals have little to say about Crystal Eastman’s role from 1920 on, in part because Eastman withdrew in 1921, citing ill health. Due to a childhood bout with scarlet fever, she suffered lifelong health complications, including nephritis, and died in 1928 at the age of 47. But it’s clear that Eastman’s legacy from the years leading up to 1920 is still very much part of our organization’s DNA. She threw herself into campaign after campaign combining organizational acumen and exquisite speaking and writing skills with vision and resilience in generating or shifting strategies to advance her goals.

Reforming the Law

Crystal Eastman had to learn early in her career how to sidestep gender discrimination. She graduated New York University Law School in 1907 second in her class, eager to practice law. But being a woman, she was unable to find a position as a lawyer. Despite this setback, she blazed a path to revolutionizing the law — in the area of workers’ compensation — within only a few years.

She took a job leading a team that conducted the first comprehensive study of the causes of workplace accidents and their consequences for workers’ families. Her work led her to publish an article and then a book, “Work-Accidents and the Law” (1910), arguing that the deck was unfairly stacked against workers who had been injured on the job. Workers or their families could get compensation for lost wages and medical expenses only if they succeeded in proving in court that their employers had been negligent, under arcane court-made law that heavily favored the employers. Rather than arguing for the smaller fix by asking the courts to change the law, Eastman made the more radical argument that legislatures should require employers to share the risk of workplace injuries and compensate workers without requiring them to prove employer fault at all.

A newspaper clipping from the Los Angeles Sunday Herald on October 09, 1910 featuring Crystal Eastman

Library of Congress

Her work generated national attention. In 1909, Gov. Charles Evans Hughes appointed Eastman to New York’s Employers’ Liability Commission, which elected her as secretary. She was, not surprisingly, the only woman on the commission. A New York Herald article finding this appointment newsworthy offers a glimpse of contemporary reactions to woman lawyers. The title of the article, “Portia Appointed by Governor,” compares Eastman to a fictional character who only pretended to be a lawyer. The article also dwells on her physical appearance, although this suspiciously sexist focus is partly explained by the fact that Crystal Eastman was six feet tall and considered a stunning beauty.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Eastman drafted what became the first state workers’ compensation law. The New York Legislature promptly enacted the revolutionary scheme in 1910. But legislative or legal victories do not always remain won. On March 24, 1911, the New York Court of Appeals struck down the law, ruling that it violated the state constitutional due process rights of employers.

On March 25, the day after the court’s opinion was published, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City killed 146 workers (123 of whom were women). With no state workers’ compensation law in effect, families of the victims recovered almost nothing. Public opinion shifted. The people of New York subsequently amended the state constitution to allow the legislature to reenact a no-fault workers’ compensation law. Laws based on Eastman’s model rapidly spread around the nation.

Not content with achieving compensation for victims of accidents, Eastman set out to find better ways to prevent industrial accidents, later becoming an investigating attorney for the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations under the Wilson administration.

The Campaign for Women’s Suffrage

In 1911, Eastman moved to Milwaukee to join her new husband, Wallace Benedict, and took a job as campaign manager of the Wisconsin Political Equality League. Her challenge was to develop and run a campaign for a 1912 state referendum on women’s suffrage — a task that showcased and developed her truly extraordinary array of talents. She embarked on a public speaking tour around the state and was such a compelling orator that she received press attention daily. An obituary of Eastman said that “when she spoke to people — whether it was to a small committee or a swarming crowd — hearts beat faster and nerves tightened as she talked.”

In addition to capitalizing on her own speaking and writing ability, Eastman was a proficient and innovative organizer. Wisconsin brewers, fearful that women voters might vote for temperance and thus limit their livelihoods, mounted a surprising disinformation campaign. Brewer-controlled newspapers tried to woo pro-temperance votes by asserting, incorrectly, that where women got the vote, saloons flourished. Eastman hired a detective to prove that this was untrue and used the detective’s report to convince the attorney general to threaten them with prosecution.

When the brewers nevertheless continued to publish this false claim, Eastman organized workers to buy up all copies of the newspapers involved, clip out the article, and send it to saloon keepers in order to encourage their support for the initiative. She fought a move to place the suffrage referendum on a separate pink ballot, but lost. Of course, victory was always going to be an uphill battle because women could not vote. Ultimately, the men of Wisconsin voted the referendum down two-to-one.

After this disappointment, Eastman concluded that more aggressive organizing tactics were needed. She joined Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, Eastman’s fellow student at Vassar, in founding the radical Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage to promote a federal constitutional amendment known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment rather than laborious state-by-state campaigns.

Members of the Congressional Union pasting advertisements announcing the procession organized by the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage May 9th, 1914

Library of Congress

Eastman also served on the executive committee of Paul’s National Woman’s Party (NWP). The party pressured candidates to take a positive position on suffrage, employing leverage from the voting power women had already gained in nine states. The NWP targeted the Democratic Party for opposing suffrage, although its leaders did not necessarily endorse candidates who agreed with their position. Charles Evans Hughes, the 1916 Republican presidential candidate, supported suffrage, but Eastman preferred Woodrow Wilson, a non-supporter whom she thought more likely to preserve the peace.

The NWP also promoted dramatic forms of direct action, similar to techniques the ACLU employed during its early years. These included massive demonstrations in D.C., one of which included at least one representative from each of the 435 congressional districts. Another tactic was daily picketing of the White House. The picketers accused Wilson of hypocrisy for supporting democracy abroad but not for half the American people. In the highly charged atmosphere surrounding World War I, the demonstrators were regarded by many as unpatriotic and were met with verbal and physical hostility.

From 1917-18, nearly 500 picketers were arrested on charges of loitering and obstructing the sidewalks; 170 women were incarcerated. No one was arrested for harassing the demonstrators. While in prison, these women suffered harsh treatment and some, following the example of British suffrage leader Emmeline Pankhurst, engaged in hunger strikes and were subjected to force feeding. These protesters were among the first victims of World War I-era suppression of dissident speech.

By the time the 19th Amendment finally passed Congress in 1919, public opinion had shifted sufficiently that Wisconsin vied to become the first state to ratify the amendment. This could not have happened without the systematic and forceful campaigns of national organizations, including the Congressional Union and NWP, which provided models for future ACLU work.

The Anti-War Movement Backlash

By 1915, Eastman had returned to New York and founded the American Union Against Militarism, along with Jane Addams, another ACLU founder, and other prominent pacifists. Eastman became executive director after Roger Baldwin declined to move to New York for the job. In its early days, the AUAM successfully led a campaign opposing compulsory military training in school physical education courses, and it was instrumental in organizing a 1916 “people’s diplomacy campaign” that helped to avert an American war with Mexico.

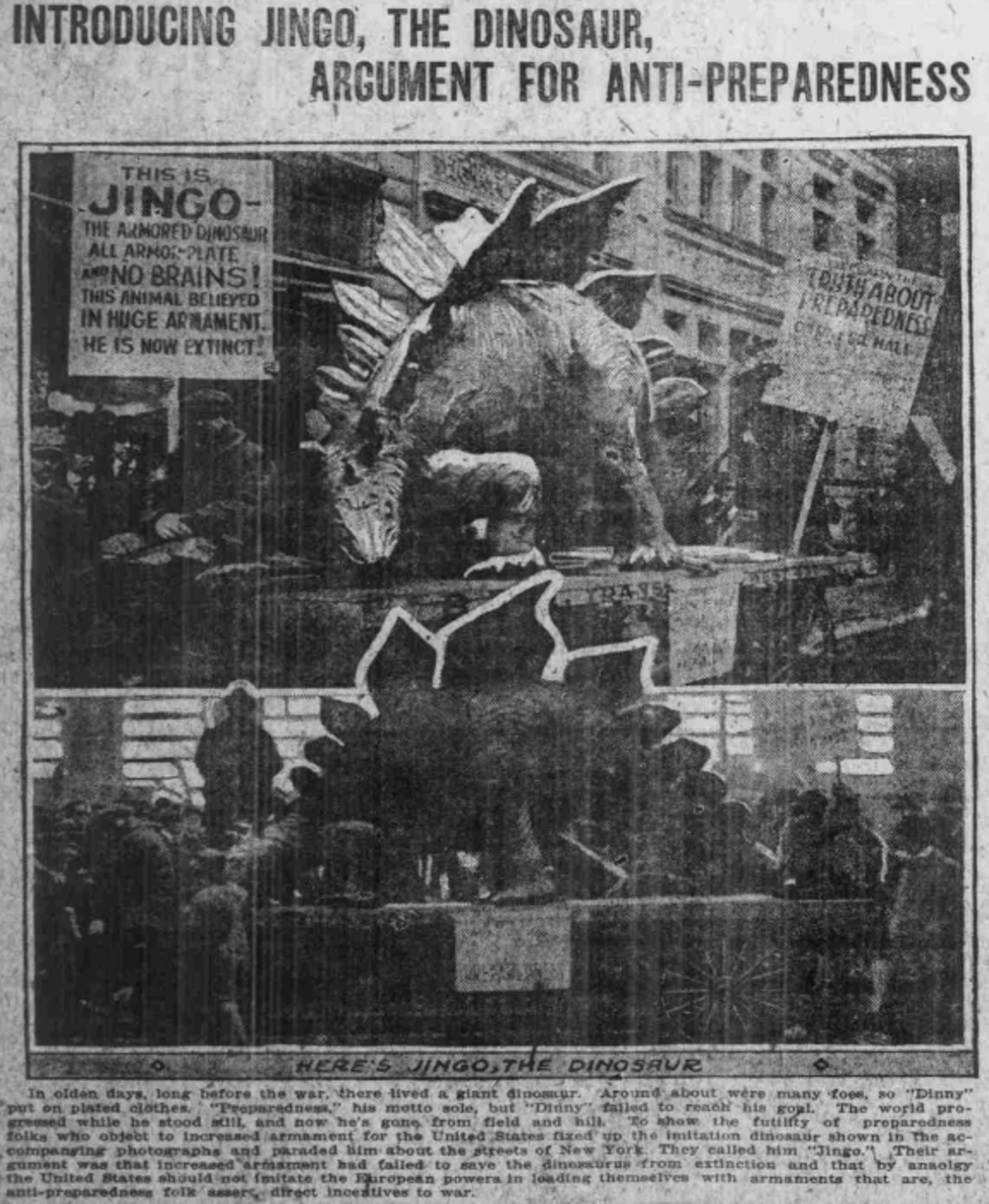

During the same period, Eastman also served as executive secretary of the Woman's Peace Party (WPP), which she had co-founded with Jane Addams and suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt in 1915, and as president of that organization’s radical New York City branch. The WPP attracted 50,000 members, distributed 600,000 pieces of literature, and engaged in confrontational and theatrical public protests. Graphic antiwar displays included a papier-mâché construction called “Jingo the Dinosaur” (“All Armor Plate – No Brains”) whose lack of intelligence was said to have led to its extinction.

A newspaper clipping from the Bridgeport Daily Farmer on April 07, 1916, featuring Jingo the Dinosaur

Library of Congress

Eastman exhausted herself on these multiple projects, working 16-20 hours a day in the period leading up to the U.S. declaration of war in April 1917, even after she became pregnant. In March 1917, Roger Baldwin agreed to move to New York and take over as director. Her first child, Jeffrey Fuller, by her British second husband, Walter Fuller, was born on March 19. Jeffrey would work for the ACLU later in his life.

Within a few months, Eastman was back at work. The entry of the U.S. into World War I in April and the subsequent passage of the Espionage Act, which adopted a broad and vague description of speech that would be considered to be harmful to the war effort, necessitated a change of approach.

By July, Eastman and Baldwin, with Norman Thomas, had instituted the National Civil Liberties Bureau, a division of the AUAM, with Baldwin serving as director and Eastman as a member of the directing committee and secretary. As Eastman had envisioned, the bureau, which subsequently became the ACLU, focused on the civil liberties of dissenters, including conscientious objectors and people who spoke out against World War I or conscription. From 1917 on, the NCLB and its cooperating attorneys defended people prosecuted under the Espionage Act, but rarely won a case in the unsympathetic courts.

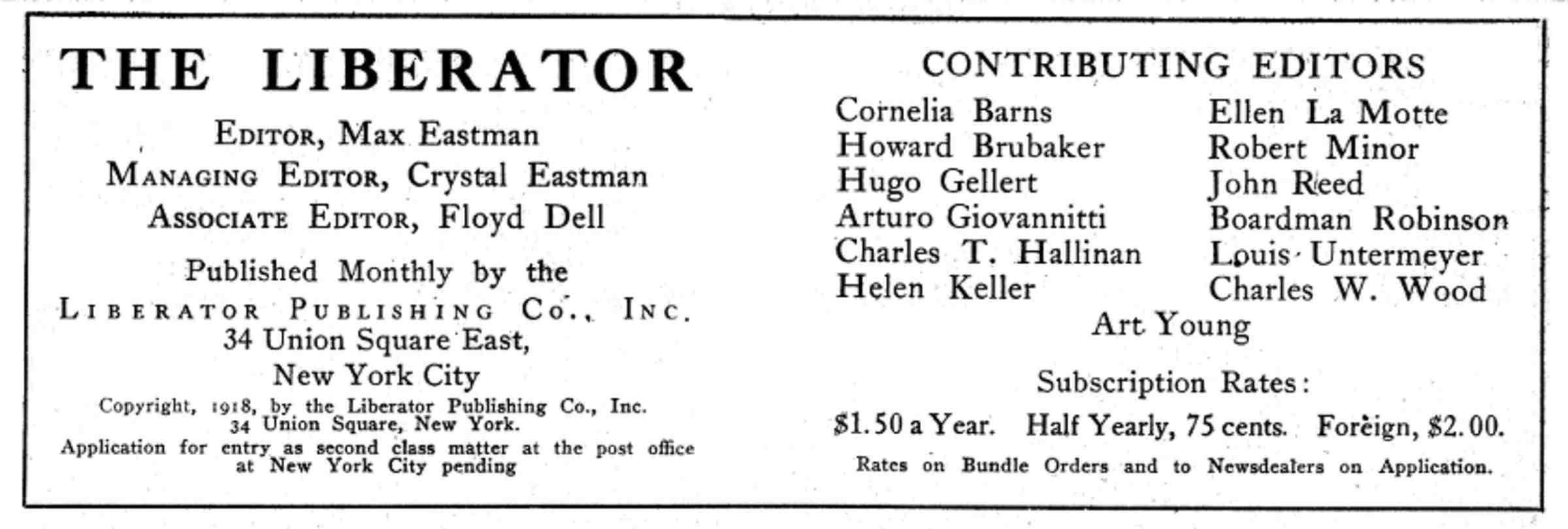

Eastman had a personal as well as a political stake in protecting dissent. She had seen her fellow suffragists arrested and mistreated for engaging in demonstrations. And The Masses — a radical and innovative magazine of art, politics, and literature edited by Crystal’s brother Max Eastman, with substantial participation by Crystal as both editor and writer — was forced to shut down in 1917 when the postmaster general denied the magazine a mailing permit because of its antiwar stance. Max and other editors were tried for violating the Espionage Act in two trials. Both ended in hung juries.

The Campaign for Equal Rights for Women

Although the early ACLU did include women in many capacities, the organization did not immediately set out to promote women’s rights. That position corresponded with the preference of most 1920 suffragists, who regarded the passage of the 19th Amendment as having achieved their goal and who feared that any declaration of equality might undermine hard-won protectionist legislation.

Crystal Eastman disagreed. “A good deal of tyranny,” she said, “goes by the name of protection.” Her 1920 speech, “Now We Can Begin,” is listed by the American Rhetoric website as number 83 of the 100 most influential American speeches of all time and is still anthologized in histories of women’s rights. Eastman and Alice Paul wrote and promoted the Equal Rights Amendment, first introduced in Congress in 1923 and finally approved by Congress in 1972 — although never ratified by a sufficient number of states. “The very passion with which it is opposed,” Eastman remarked, “suggests that it is vital.”

The ACLU eventually decided to support the Equal Rights Amendment in 1970, when Dorothy Kenyon, the organization’s groundbreaking women’s rights activist and board member, changed her mind and advocated support. Eastman said almost a century ago, “This is a fight worth fighting even if it takes ten years.” Even today, after so many decades, the ACLU is still involved in the battle over ratification of the ERA, as well as a vibrant women’s rights docket Eastman would have admired.

Eastman’s concept of civil liberties was broader than the fledgling ACLU’s in other ways, too. She was an early advocate for birth control, legalization of prostitution (at a time when alleged prostitutes but not their patrons were prosecuted), and economic support for mothers and children. She believed international collaboration on civil liberties issues to be essential, as did Roger Baldwin. But the ACLU board disagreed and limited the ACLU’s mandate to domestic civil liberties.

Eastman’s departure from the ACLU in 1921 was attributed to her poor health. But there were certainly other contributing factors. For one thing, she needed to earn a living. Blacklisted in 1919-20, she was unable to find enough paying work in New York, especially after The Liberator — the magazine she and her brother, Max, started in 1918 to replace The Masses — was taken over by new management and became a Communist Party organ.

The names of the editors of The Liberator

Marxists.org

She also had a British husband. In 1922, Crystal decided to live in London, where she made a living by writing for various publications, including The Nation, mostly on issues of women’s equality and socialism. (As a side note, Eastman was outraged that when she married a citizen of another country she automatically forfeited her American citizenship even though she was still living in the United States. Jeannette Rankin, the first woman elected to Congress and a co-founder of the ACLU, introduced a bill to change that provision, which eventually passed in 1922.)

Unhappy as an expatriate, Crystal Eastman returned to the United States in 1927, expecting her husband to join her. But a month after her departure, Walter died of a stroke. Crystal died less than 10 months later. During those months, she organized a massive 10th anniversary celebration for the editor of The Nation, Oswald Garrison Villard.

Writing a Woman’s History

The historian Gerda Lerner posited that there are three stages of writing about women in our histories: First, the compensatory phase, where the presence of women is acknowledged; second, the contributions phase, where specific ways in which women made contributions in male-dominated narratives are identified; and third, when histories center on the women themselves rather than casting them as bit players in the histories of men.

Histories of the ACLU center on Roger Baldwin, who was the first and long-time director from 1920-50. We can only wonder how Eastman herself would have assessed her contributions to the ACLU and her collaboration with Baldwin — and how the ACLU might have been different if her health and other circumstances had not led her to step aside. Might she have become the ACLU’s first director?

As a number of historians have noted, Eastman, despite her very public life and stature, disappeared from American history for 50 years. Blanche Wiesen Cook, who published a book of Eastman’s writings in 1978, had this explanation: “History tends to bury what it seeks to reject, and it was no accident that male-dominated history excised the leadership of women who made essential connections between sexism, racism, poverty and war.” Crystal Eastman saw those connections and made them her life’s work.

Interest in her legacy revived to some extent among pacifists in the 1960s and then again in the 1970s with passage of the ERA in Congress. In 1996, she was named one of the 50 most influential women in American law, and in 2000, she was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls — a fitting capstone for someone who grew up by the shores of Lake Seneca.

According to the Oxford University Press lists, the first full-length biography of Eastman will be published, at last, in November 2019 -- just in time for the ACLU centennial.

Susan N. Herman is the president of the American Civil Liberties Union. She holds a chair as Centennial Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School, and writes extensively on constitutional and criminal procedure topics.

A note on published sources: Blanche Wiesen Cook’s book, Crystal Eastman on Women and Revolution (1978) contains an introductory biographical essay and a collection of Eastman’s writings. Sylvia Law published several articles on Eastman. John Fabian Witt’s book Patriots and Cosmopolitans (2007) contains an interesting chapter on Eastman’s internationalism and the origins of civil liberties. Encyclopedia and other internet sources are inconsistent and not wholly reliable, often repeating inaccuracies from other sources.

Matters of Principle

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Donate to the ACLU

The ACLU has been at the center of nearly every major civil liberties battle in the U.S. for more than 100 years. This vital work depends on the support of ACLU members in all 50 states and beyond.

We need you with us to keep fighting — donate today.

Contributions to the ACLU are not tax deductible.