Mr. ACLU and the General

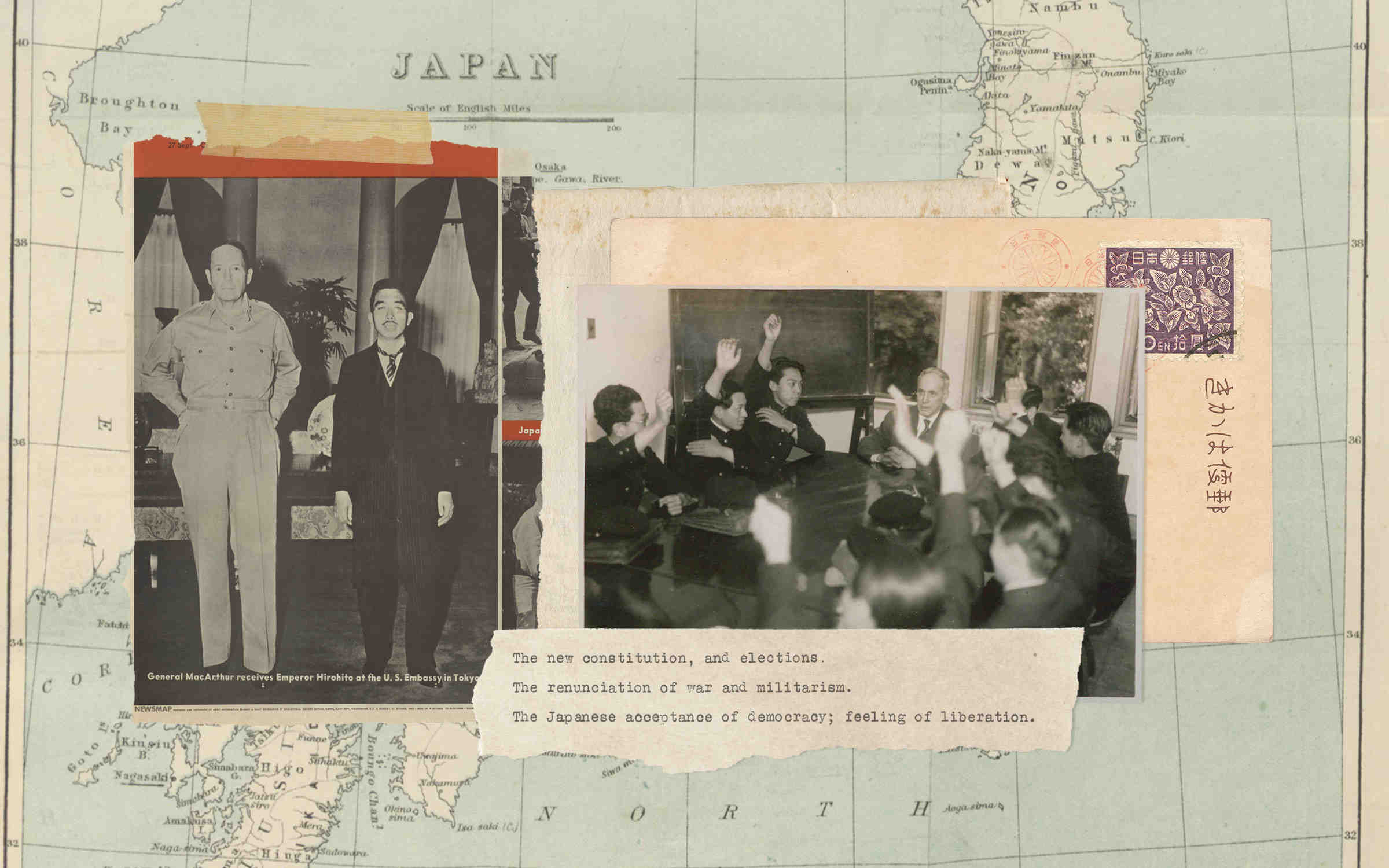

Douglas MacArthur, circa 1945.

Harry S. Truman Library

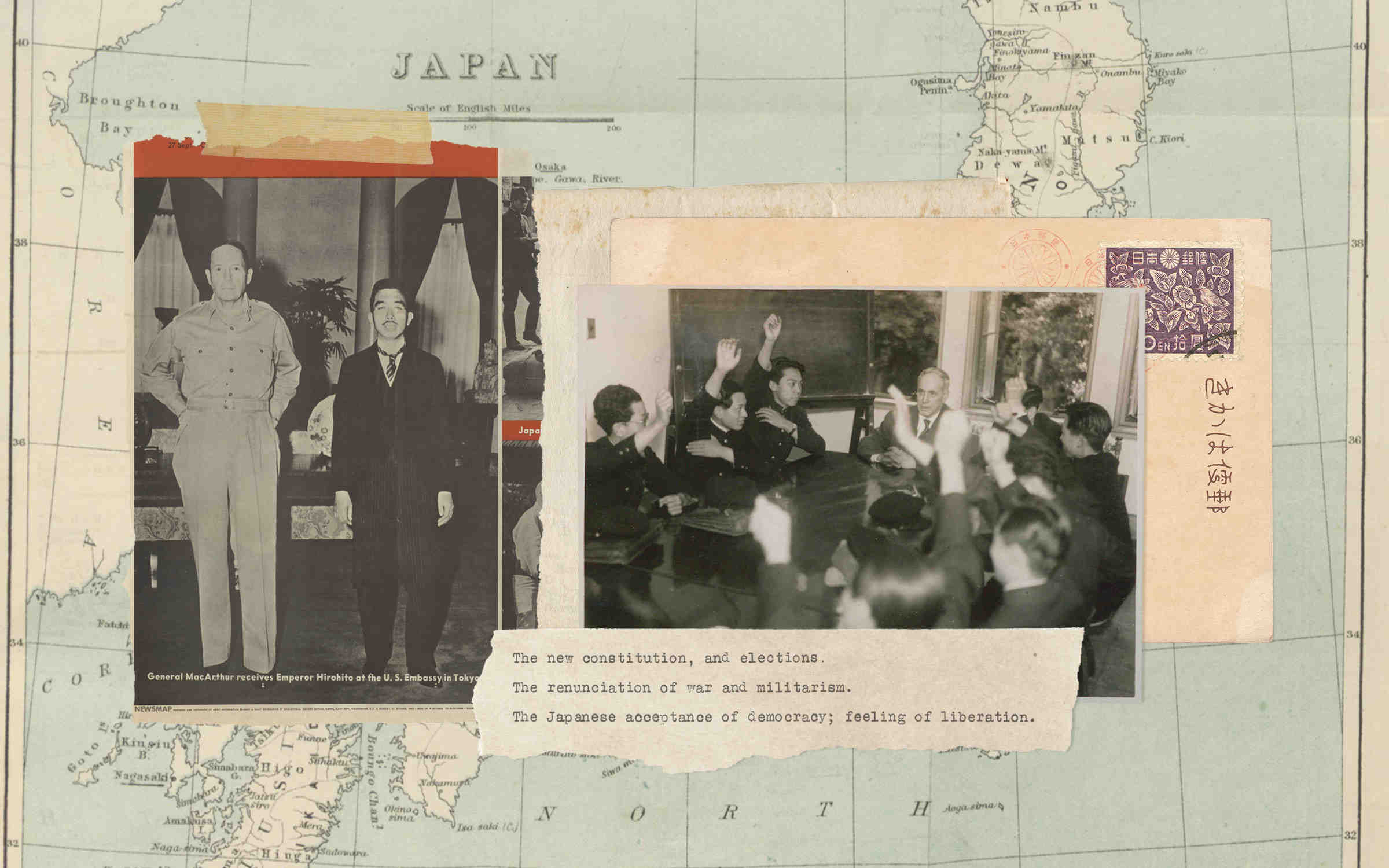

Some thought the longtime ACLU chief got bamboozled. Or at least that the five-star general exploited him, using his guest’s reputation as “Mr. ACLU” to paper over the manner in which he, the supreme commander of the Allied powers occupying Japan after World War II, intended to remake the former Axis state.

Others simply believed it was not possible: How could friendly, even affectionate, relations exist between a longtime self-professed radical and the man still recalled for using tear gas and tanks against thousands of protesting World War I veterans, known as the Bonus Army, at the height of the Great Depression?

Yet somehow the curious partnership between ACLU founder Roger Nash Baldwin and Gen. Douglas MacArthur not only occurred but thrived. Perhaps it did because MacArthur pulled a fast one over on Baldwin, using the latter’s reputation as the nation’s leading civil libertarian to strengthen the American-led postwar occupation of its defeated foe. Japan didn’t undergo the total transformation many of its own citizens thought was warranted, but it also avoided a hard turn to the right or left that other nation-states, including some in Asia, underwent after WWII. Meanwhile, a foundation was laid for a new Japan, one that proved enormously productive and at least moderately democratic in the early postwar period.

An Unlikely Proposal

Baldwin’s eagerness to work with MacArthur was in keeping with his decades-old determination to extend human rights to the international realm. During the 1920s, he became involved with the International Committee for Political Prisoners, the American League for India’s Freedom, and the International Congress Against Colonialism and Imperialism.

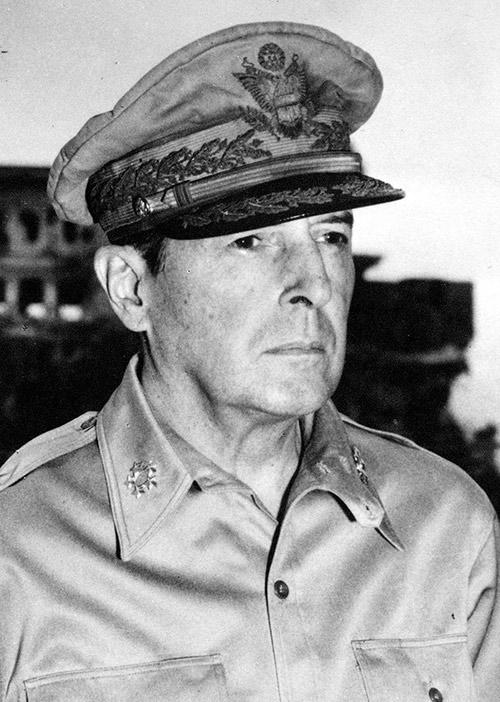

Photograph of Roger N. Baldwin at Tokyo Imperial University

Roger Nash Baldwin Papers. Reproduced courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

With the advent of the Cold War and a less hands-on approach to serving as the ACLU’s executive director, Baldwin turned his attention once again to global affairs. The United States, he noted, had promised self-government, which colonial peoples were demanding. However, he reflected, “our treatment of racial minorities denies our moral claim to democratic leadership in the world.” Baldwin pointed to Mahatma Gandhi as “the supreme apostle of freedom in a far greater frame than nationalism” and to India as “the touch-stone to the future of most of the human race.”

Baldwin’s willingness to assist Gen. MacArthur also continued a path he had undertaken over the several years prior. Although he had been supportive of alliances between left-of-center forces against fascist depredations, Baldwin had dramatically shifted course following the announcement of the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression Pact during the summer of 1939. Like so many on the American left, including within the Communist Party of the United States, Baldwin was stunned by the news.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

“I think it was the biggest shock of my life,” he wrote. “I never was so shaken up by anything as I was by that pact — by the fact that those two powers had got together at the expense of the democracies.”

To the delight of his old friend and anarchist Emma Goldman, Baldwin no longer considered the communists trustworthy. “The Nazi-Soviet pact made you feel that suddenly the Communists were different people.”

Baldwin’s anti-communist stance made him receptive to MacArthur’s entreaties, as did his willingness to establish amicable relationships with government officials.

Shortly, Baldwin began supporting a change in the ACLU’s leadership, backing the removal of those who continued viewing the Soviet Union favorably. Even the wartime partnership between the U.S., Great Britain, and the Soviet Union didn’t change Baldwin’s new perspective. Thus, as the Cold War emerged out of the ashes of World War II, Baldwin’s anti-communist stance made him receptive to MacArthur’s entreaties, as did his willingness to establish amicable relationships with government officials, even those like FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who viewed him with grave mistrust. It was hardly surprising, then, that Baldwin, at one point a fervent antimilitarist, proved eager to deal with MacArthur.

In early January 1947, a letter from the War Department’s Special Staff arrived at the ACLU’s national office in Manhattan, indicating that Gen. MacArthur’s headquarters sought out Baldwin’s services as a civil liberties consultant in both Japan and the U.S.-zone of occupation in Korea’s southern half. This undoubtedly delighted Baldwin, who had often urged his ACLU compatriots to extend the organization’s operations overseas, but generally to little avail. Until recently viewed by the FBI as an internal security threat, Baldwin feared that the House Committee on Un-American Activities, emboldened by the new domestic Cold War atmosphere, might contest his appointment.

Read the War Department's letter inviting Roger Baldwin to Japan and Korea

While falsely claiming he had “always been anti-Communist,” Baldwin expressed no wish to embarrass either the ACLU or the War Department. He actually met with J. Parnell Thomas, HUAC’s new chair, who expressed no opposition to Baldwin’s proposed sojourn as a private citizen. Since the early 1930s, Baldwin’s relationship with government figures, which he continued to cultivate, had become more amicable. John Haynes Holmes, ACLU board chair, lauded the possibility of Baldwin’s mission to Asia, judging it “a kind of crown of recognition and reward for his many years of self-forgetting service of a basic interest of democracy and peace.”

Baldwin quickly learned that MacArthur had agreed to his terms — he would operate as “a private citizen going at General MacArthur’s personal invitation at his own expense.” Already serving as a consultant to the United Nations on civil rights for the International League for the Rights of Man, Baldwin obtained “a too flattering” note of introduction from Henri Laugier, assistant U.N. secretary general. Baldwin also boasted credentials as a representative of the World Federation of the United Nations Association.

Ironically, for one who had long been reviled for his radical perspectives, Baldwin now garnered kudos from conservative publications, seemingly thrilled about his impending visit. By contrast, the pro-communist New Masses assailed him, particularly for his purported closeness to the reactionary HUAC chair Thomas. The New Leader, a social democrat publication, defended Baldwin and charged that the ACLU was “the target of Stalinist vilification.”

Read Roger Baldwin's memo to the ACLU Board about the "New Masses" article

‘Mr. Baldwin’ Arrives

Photograph of Roger N. Baldwin at Tokyo Imperial University.

Roger Nash Baldwin Papers. Reproduced courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

On April 12, Baldwin arrived in Tokyo, greeted by a military chauffeur and private limousine, which took him to the Imperial, the city’s top hotel. The driver and vehicle, at Baldwin’s disposal for the duration of his stay in Japan, sported a sign on the window, “VIP.” At the U.S. Army headquarters, Baldwin was given an office, secretary, and interpreter. He declined use of a military aide. The next day, Baldwin lunched at the American Embassy, encountering Douglas and Jean MacArthur, the general’s wife. MacArthur immediately exclaimed, “Mr. Baldwin, we have been waiting for you for a long time. I am delighted you have come at last.” They entered the dining room with MacArthur’s arm draped around Baldwin’s shoulder.

MacArthur expressed his need for assistance in nourishing civil liberties in occupied territories. Indicating that he expected his staff to fully cooperate with Baldwin, MacArthur also urged his guest, “I want you to see everybody, go everywhere; every door is open to you. I want you to tell me what you think is wrong about the Occupation policies in regard to the democratic purposes that we’re trying to instill in the Japanese people.”

Baldwin was delighted. A letter from Baldwin dated May 1 and addressed to “Friends” back in the United States referred to MacArthur as “a charming, wise, witty, most unmilitary man with a strong sense of mission, a genuine democrat who sees his role in large historic outlines and with great confidence in the Japanese.”

Read Roger Baldwin's memo from Japan about MacArthur

During his stay, Baldwin held interviews and participated in meetings between Americans and Japanese, involving military men, communists, members of Japan’s royalty, and common citizens. As Baldwin saw matters, they were all, in some manner, participating in “this amazing experiment in transplanting democracy.” He helped to set up three associations connected to civil rights, the U.N., and Japanese Americans, respectively.

Baldwin showed up at war crimes trials, the Allied Council, and political gatherings in cities and the countryside. He also dined with Americans staying in fine Japanese homes requisitioned by U.S. forces as well as with Japanese in their own homes. Baldwin also spent time with Emperor Hirohito. Arriving with presents for Hirohito’s children — candy, pencils, and pens — Baldwin was ushered into the administration building’s grand reception room. A smiling Hirohito approached, shook his guest’s hands, and stated, “Mister Baldwin.” Conversing for less than an hour, they talked about the treatment afforded Japanese citizens in the United States and interactions involving Japanese groups and U.N. agencies.

General MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito at the U.S. Embassy, Tokyo, 27 September, 1945

When Baldwin prepared to leave, Hirohito grasped his hands and expressed appreciation for the gifts, which Japanese newspapers duly noted. A press release underscored Baldwin’s belief that Hirohito seemed highly receptive to liberal and democratic values. The next day, Baldwin got a phone call from the Japanese Foreign Office asking if he could have tea that afternoon with Prince Takamatsu, Hirohito’s younger brother.

Writing to MacArthur on May 6, Baldwin applauded the joint American-Japanese effort. The people of Japan seemed capable of grasping democratic institutions, he wrote. And the U.S. military, for its part, appeared prepared to foster Japan’s democratization. Baldwin told MacArthur, “You gave an amazingly effective staff imbued with your own ideals and practical statesmanship.”

Nevertheless, Baldwin offered several suggestions to inculcate civil liberties in Japan, including ending censorship, restoring international mail service to also kindle “democratic contacts,” affiliating a Japanese group with the U.N., encouraging attendance at international conferences by “suitable Japanese representatives,” and resuming American funding for educational institutions.

Read the May 1947 letter to MacArthur from Roger Baldwin

Within four days, Baldwin drafted a confidential letter for ACLU leaders, in which he again sang MacArthur’s praises. “His observation on civil liberties and democracy,” Baldwin insisted, “rank with the best I ever heard from any civilian — and they were incredible from a general.” Still, “a terrific job” loomed ahead, with the American military needing to allow the Japanese to take control of government operations. Even there, Baldwin believed “General MacArthur’s judgment on that is obviously to be trusted.”

Read Baldwin's "Balance Sheet of the Occupation of Japan"

While in Japan, Baldwin accepted an invitation to visit South Korea from Gen. R. Hodge, the American military governor in that country. He agreed to a short stay in South Korea, where he met President Syngman Rhee, whom he called “an agent of reaction” but “such a charming old gentleman, so kindly and urbane.”

His time in Japan and South Korea, Baldwin later declared, had “been the two most stirring months of my life.” He expressed regret for his inability to completely capture what was transpiring in Japan, “one of the great dramas of history.” Readying to depart on June 8, Baldwin wrote in his farewell note to MacArthur, “I leave with consciousness of the amazing experiment in democracy here made possible and so promising chiefly by your spirit and vision. No possible criticism of detail can detract from what is a great historical achievement already assured.”

In his extended report to the ACLU, Baldwin referred, undoubtedly hyperbolically, to his recent time in Asia as “the most useful period of time I have ever spent toward the Union’s objectives.” A few weeks following his return from overseas, Baldwin wrote a document, “Shogun and Emperor.” To his amazement, his wholly positive evaluation of Douglas MacArthur was greeted with skepticism by many fellow ACLU board members. MacArthur possessed all but unlimited authority to usher in the U.S. program “of disarming, demilitarizing, and democratizing Japan,” and Baldwin concluded that the general appeared to be “engaged in a crusade . . . a crusade for democracy.”

MacArthur's Reversal

In late 1949, the ACLU announced that Baldwin was stepping down as executive director but would continue working for the organization, focusing on “international standards of civil liberties.” Among the tributes he received was a handwritten note from the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Tokyo. General MacArthur’s message stated, “Baldwin’s crusade for civil liberties has had a profound and beneficial influence upon the course of American progress.”

Suffice it to say, MacArthur knew his man, well appreciating how receptive Baldwin was to flattery from establishment figures. Over the years, for instance, America’s most celebrated champion of civil liberties had repeatedly been taken in by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who despised and distrusted him. Now, during the early Cold War period, MacArthur appeared to have bowled over a man who had long been one of the nation’s leading antimilitarists.

With the outbreak of the Korean War, during which MacArthur and President Truman clashed, resulting in MacArthur’s firing, Baldwin’s analysis of occupation policies in Japan shifted course, for a time, at least. In a letter dated May 15, 1952, to Dick Deverall, who had served in Japan on the military government’s staff alongside MacArthur, Baldwin said, “Things shifted pretty badly as you know, after you and I quit and the General shifted his policies out of fear of the Communists.” The Japanese constitution, devised in 1947, provided for free expression. Nevertheless, legal changes soon allowed for restrictions on public employees and demonstrations. Local safety ordinances also curbed freedom of assembly.

Baldwin’s lengthy battle to defend civil liberties in the United States was determined and often heroic. At times, he hoped to extend that quest beyond American shores. Thus, he jumped at the chance to assist in the reconstruction effort in Japan. Baldwin’s time there was short but memorable, leading him to believe that his near life-long quest to safeguard civil liberties could indeed be carried to the international stage. Baldwin thought he could make a difference overseas as he had at home. Perhaps, in some small way, he did in postwar Japan.

Read More

January 1947 ACLU Board meeting minutes

March 1947 Letter from the ACLU Board Chairman to MacArthur

June 1947 Roger Baldwin's "Memorandum on Korea"

Roger Baldwin's "Balance Sheet of the Occupation of Korea" Letter

June 1947 ACLU Board meeting minutes

Robert C. Cottrell is the author of “Roger Nash Baldwin and the American Civil Liberties Union” (Columbia University Press, 2000) and “Roger Baldwin” (Harvard Square Library).

Donate to the ACLU

The ACLU has been at the center of nearly every major civil liberties battle in the U.S. for more than 100 years. This vital work depends on the support of ACLU members in all 50 states and beyond.

We need you with us to keep fighting — donate today.

Contributions to the ACLU are not tax deductible.