Ricardo and his daughter were separated at the border in December 2017. It would be six months before they spoke again.

'When I Saw Her I Felt My Soul Ache'

A Father Is Reunited With His Four-Year-Old Daughter After Nearly 10 Months Apart.

By Ashoka Mukpo

October 2nd, 2018

Caught at the Border

On the day last December when Ricardo and his daughter Luna crossed the border into South Texas from Mexico, it was unusually cold. For the first time in over a decade, snow had fallen in McAllen, Texas, and residents of the city had woken up to the rare sight of the arid brown landscape dusted in white. For Ricardo, that snow meant danger. The two had left Guatemala about a month ago, but they hadn’t packed for cold weather, and Luna, only three years old, didn’t have the right clothing for the freezing temperature. Deciding that it would be safer to take his chances with the Border Patrol rather than being exposed to the elements, Ricardo and his daughter set off along the Rio Grande to look for an agent.

A few hours later, they found one, who took the two of them into custody and placed them in a Border Patrol processing facility known as La Hielera — "The Icebox." It was the last afternoon Ricardo and Luna would spend together for months, although neither of them knew it yet.

“Ricardo” and “Luna” are pseudonyms. Concerned about the repercussions of telling his story, he asked the ACLU to protect his identity. Within a week of being arrested outside McAllen on that day last December, Ricardo was deported to Guatemala. But it wasn’t until last Friday — 288 days later — that Luna, now four years old, was sent back to join her father in Guatemala. In all, Luna spent over nine months in immigration detention, including a six-month stretch when she was offered no opportunity to contact either Ricardo or any of her other relatives.

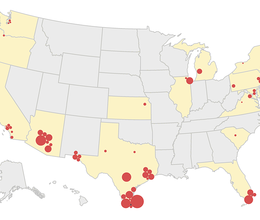

On June 26, U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw ordered the federal government to reunify all separated children with their parents within 30 days. For those under five years old, the deadline was 14 days. But Ricardo’s daughter remained in detention for more than 10 weeks past the deadline for reuniting the younger group — and according to the government’s own data, she’s not alone. Out of 2,654 children identified as potentially having been separated from their parents, 358 remained in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) as of Sept. 27.

In all, Luna spent over 9 months in immigration detention.

Those children have a myriad of stories. Some have parents who’ve had to make the difficult decision of allowing them to go through the asylum application process by themselves. Others are being held due to “red flags” the government has placed on their parent, and some may have crossed the border with people who weren’t their parents. Others have deported parents that haven’t yet been located. But some are simply in limbo, awaiting reunion with parents who’ve clearly indicated that they want their children back.

Until Sept. 21, Luna was in that latter group of children. Her parents didn’t have red flags, nor were they among those who are missing or haven’t confirmed their intent to be reunified with their children. And according to her lawyers, her detention was likely one of the longest of any child affected by the Trump Administration’s family separation policy. There is no obvious reason why she was held long past the deadline to reunify her with her parents, and her case provides a window into the confusing limbo that some other children likely remain trapped in.

A Brutal Separation

In April, Attorney General Jeff Sessions explicitly spoke about the government using hardline policies intended to deter people from crossing the Southern border, including the practice of separating them from their children. Ricardo’s story is an example of how the practice was being carried out months before then.

When Ricardo and Luna arrived at the detention facility, at first they were held in the same caged area. Ricardo says he assumed they’d be brought in front of an immigration judge together, after which he’d find out whether they were to be deported or allowed to remain in the United States. It wasn’t his first time attempting to cross the border — he’d been deported twice before — but it was the first time he’d brought one of his children with him on the journey.

But later that night, Ricardo was shocked to learn that he and Luna were going to be separated the next day and held in different facilities. “That first night they said they were going to separate me from my daughter,” he remembered. “And they harshly told me, you’re going back, and she is going to stay here.” Ricardo says Luna picked up on the officer’s comment. “When she heard that, she got very sad and cried a lot. She said, "Daddy, I don’t want to be separated from you. I want to go with you, why did the policeman say that?”

Ricardo spent the rest of the night holding Luna in his arms, trying to calm her down. When he asked for water, an officer told him he “should have brought his own drink.” Early the next day, officers came to take the young girl away. “When they took her away it was a very rough separation,” he said. “I was hugging her very hard while she was crying. I begged and cried, and said please don’t do this. My daughter is a child, what is she going to do by herself without me?” He said an officer responded by telling him, “You knew what you were risking. This isn’t your country or your laws. You violated the law by entering here illegally.”

Ricardo watched helplessly as his daughter was locked in a cage across from his. “I could see her crying and screaming,” he remembered. “After two hours they took her away.” It was, he says, the worst moment of his life. “I asked for medical help because my chest hurt. I thought I was going to go crazy because of the suffering.”

Ricardo watched helplessly as his daughter was locked in a cage across from his.

Twenty-four hours later, Ricardo was transferred to what he describes as an “immigration prison,” where he says he was told that he was being charged with a crime for crossing the border and that he’d soon appear before a judge. When he asked for information about his daughter, immigration agents told him that he’d be reunited with her after a judge made a determination about his status. “They promised me they’d return my girl as soon as possible once a judge decided what was going to happen to us,” he said.

But a week later, he was visited by ICE agents who told him that he was going to be deported immediately instead: “They handcuffed me and accompanied me to the plane, without my daughter, and said, don’t worry, you’ll be with her. You just don’t have the right to see an immigration judge.” Ricardo was confused and anxious over the prospect of being sent to Guatemala without his daughter, but he had no choice but to comply.

On Dec. 15, just over a week after he and Luna were arrested by the Border Patrol, Ricardo landed in Guatemala City. “I arrived with the promise that my daughter would be with me in a week,” he said. But, in fact, months would pass before he would even learn where she was.

An Anguished Wait

Before he was deported to Guatemala, ICE agents handed Ricardo a sheet of paper with a toll-free phone number to call for information about Luna, along with her alien registration number and the name of the Texas shelter where she was being held. But Ricardo says that when he called the number, operators gave him the horrifying news that they didn’t have any information about her in the system.

In photos, Luna has a toddler’s innocent, quizzical expression, with soft brown eyes and a sweet smile. Ricardo, who returned to his home, a remote city in Guatemala, said that he was tortured by the idea of her being alone and scared in a detention facility.

“It was a great pain during the time I didn’t have access to my daughter,” he said. “Eventually somebody called me, but they didn’t give me information or a chance to talk to her or see her.” Ricardo’s wife, the mother of the young girl, was also distraught. For months, Ricardo said the two begged the American social worker who had been assigned to Luna’s case for the chance to speak to her, but they were told it wasn’t possible.

In February, Luna was transferred from a shelter in Texas to The Southwest Key Juvenile Center Campbell, in Phoenix, Arizona. Southwest Key, a private contractor that operates a number of shelters and detention facilities for unaccompanied immigrant minors, has housed many of the children who were separated from their parents this year. The company has been plagued by allegations of sexual abuse. In August, a Campbell employee was charged with child molestation after sexually assaulting a 14-year-old girl, and on Sept. 19, Arizona’s Department of Health moved to revoke the licenses of the 13 shelters the company operates in the state because of substandard background check procedures for its employees.

Luna’s social worker told Ricardo that it would be up to an immigration judge to determine when — or if — Luna would be sent to Guatemala. “They told us that if a judge decided that she has to stay there, even against the parents’ will, it would happen,” he said. “I’m her father, and I’m here with her mother. How is an immigration judge going to decide that a child is better without the embrace of her parents?”

For months after her transfer to the Phoenix shelter, Ricardo claims that Luna had no contact with her parents. They knew she’d been moved to Arizona and were told it would be some time before she could appear before a judge. But by late spring, the Trump administration’s family separation crisis became a political firestorm, gaining broad media coverage after a court challenge by the ACLU. Finally, in June, Ricardo says his phone rang: “They said they were going to put me in contact with her. I was speechless.” Suddenly, her tiny voice crackled through the line. Ricardo asked if she was all right. “She didn’t reply much,” he said. “It had been a long time since she’d heard my voice so maybe it was strange for her. She said, I’m okay, I’m okay. And that was everything she said that first time.”

After that day, the phone calls became more regular, but Luna was distant and said little. Ricardo and his wife were furious that she hadn’t been sent home yet. “I want to come back. I don’t want to be here anymore,” Luna told Ricardo.

“I believe that [she] is one of the longest detained children who was separated from her parents,” said Golden McCarthy, the director of the Children’s Program at the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project, which was assigned to represent Luna. “They entered in December. It’s pretty striking, you know. That’s a lifetime for a four-year-old.” McCarthy also said that Luna’s transition to the Campbell facility was “rough for her,” and that it took time for legal advocates to gain her trust enough for her to speak with them.

"How is an immigration judge going to decide that a child is better without the embrace of her parents?"

On Aug. 10 — 30 days past the deadline imposed by Judge Sabraw for when all children under five should have been reunited with their parents — Luna finally had her court hearing. The judge signed a voluntary departure agreement that would allow Luna to be deported, but before she could return to Guatemala, an investigation was ordered to determine whether Ricardo had a suitable home for her. For Luna, this meant more than a month spent in detention past her court date, and for Ricardo, it meant an intrusive visit by investigators. They asked about his income, took pictures of his house, and even interviewed his pastor.

Ricardo was confused — if they didn’t like what they saw, what would happen? It had been nearly nine months since Ricardo and Luna were arrested in Texas, and he still didn’t have a clear answer for when Luna would be coming home. By then, he was starting to worry that the experience might change her forever.

“It’s one of my biggest fears because she’s a little girl, and she could easily suffer trauma,” he said. “I’m aware that she’s going to be emotionally affected and hurt after she returns.”

“When I saw Her I Felt My Soul Ache”

In mid-September, Ricardo finally received the news that Luna would be coming home, months after family separation became a national issue in the U.S. and long past Judge Sabraw’s deadline. The Guatemalan Consulate in the U.S. called Ricardo, telling him that she was scheduled to arrive in Guatemala City on Friday, Sept. 21, and that he should wait for a call from U.S. officials to confirm her departure. That call never came, but he left for the four-hour journey to Guatemala City last Thursday anyway.

For many deported parents in Guatemala, the journey to pick up their children can be a financial challenge. Advocates who’ve worked to find missing parents say that the cost of travel and lodging can be a heavy burden, especially for the rural poor.

But Ricardo pulled together the money to fuel his car, and the next day, he and his wife were finally reunited with Luna at a shelter that processes incoming U.S. deportees. “When I saw her, I felt my soul ache,” he said. “She was skinny and sad for all the time she hadn’t seen us. It was a sad but at the same time very joyful moment.” In pictures taken during the reunion, Luna is smiling, but she looks weary.

Having his daughter back is “like a miracle,” Ricardo said. At some points over the last nine months, he’d worried that he might never see Luna again. “Finally, we stopped suffering,” he added.

But she hasn’t spoken much since she’s been back with her family, and Ricardo said she seems quieter than she did before the separation. She told him that she was moved from facility to facility and that she had missed him, but “she talks very little,” he said.

“When I saw her, I felt my soul ache"

Luna’s reunion with her family is a relief, but it should never have taken so long. Judge Sabraw’s ruling on June 26 ordered the government to carry out reunions for children younger than five within two weeks. Luna, a three-year-old, was detained alone for nearly a quarter of her life, including for a lengthy period past Sabraw’s order. And there are still as many as 18 children under five who remain in government custody separated from their parents; some of these parents, like Ricardo, have also been deported.

Luna turned four while in detention. The trauma she endured is likely to leave lasting scars. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “the psychological distress, anxiety, and depression associated with separation from a parent would follow the children well after the immediate period of separation.”

“Nine months without seeing her is a very long time,” said Ricardo. “It’s something that’s completely unfair. I don’t know why they did that to us — she didn’t deserve it.”