(Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

Trump's New Policy is Stranding Asylum Seekers in Mexico

The administration sent hundreds of asylum seekers to Mexico with no regard for the danger they face there.

March 21, 2019

By Amrit Cheng

On Jan. 29, John, a 31-year-old asylum seeker from Guatemala, entered a border port near San Diego. He had been in Tijuana for around six weeks but was forced to wait to actually come to the San Ysidro port until his number — 1865 on the list that determines who will be next in line to seek asylum — was finally called.

It was a huge moment of relief in what had been a perilous journey. In October 2018, John (all individuals quoted and named in this article have been given pseudonyms to protect their safety) fled Guatemala after the Ronderos de San Juan, a death squad that controlled his hometown, threatened to kill him. He had been beaten by the Ronderos multiple times. He believes he was targeted because of his indigenous background, as the group would often call him slurs. The danger escalated when an animal rights group filed a report against the Ronderos for abusing stray animals in the area. The Ronderos wrongly believed that John — a dog groomer who often left food and water out for strays — had filed the report. In retaliation, they left the bodies of several dead dogs outside his house with a message: You could be next.

A man enters the Tijuana apartment where he and several other asylum seekers have found temporary lodging. Should it stop being available, they will likely be reliant on shelters or sleeping on the streets. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

The journey through Mexico had been rife with danger as well. During his train trip to the U.S. border, John witnessed a group of people, who were wearing black face masks and carrying large guns, unloading packages from the train into nearby cars.

Assuming that they were narco-traffickers, John quickly hid. But some of them heard the noise and started to look for him. John was terrified that the men would find and kill him, and he remains so to this day.

Throughout the six weeks he was required to wait in Tijuana, John feared that he could be recognized or found by the traffickers. He kept to himself and was in dread whenever he went to check in at El Chapparal, the public plaza where migrants gather to hear the numbers being called from the list.

When he was finally allowed to cross into the U.S. to seek asylum, John had every reason to believe that he would, at last, find safety. What he didn’t know was that four days earlier the Trump administration had announced a new policy of involuntarily ejecting Central American asylum seekers out of the U.S. before even hearing their asylum claims. The administration was now requiring asylum seekers to return to Mexico and stay there throughout their removal proceedings, a process that typically takes a year or more.

Looking for Safety, Turned Around Instead

John was among the first group of people forced back into Mexico in a fundamental shift in how the United States treats and processes asylum seekers. Under U.S. law, individuals have a legal right to seek asylum in the United States and that right applies when they step on American soil.

Since the enactment of the 1980 Refugee Act, the U.S. has prohibited the return of individuals to countries where they are likely to face persecution. Traditionally asylum seekers remain in the United States until their cases are resolved. Under this new policy, however, asylum seekers are assigned an initial court date within approximately 45 days of presenting themselves at the border and forced back into Mexico. They are told to come back to the port of entry on the morning of their court date.

Between Jan. 28 and March 12, the Trump administration forced 240 asylum seekers to return to Mexico, according to estimates by the Department of Homeland Security. In mid-February, the ACLU, Southern Poverty Law Center, and the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies filed a lawsuit on behalf of 11 Central American asylum seekers and several plaintiff organizations to stop the policy, charging that it violates multiple U.S. laws and the longstanding international human rights law that prohibits returning asylum seekers to danger. On March 22, a federal judge in San Francisco will hear arguments in the case, Innovation Law Lab v. Nielsen.

John, right corner, meets with the legal team from the ACLU's Immigrants Rights Project at a community center in Tijuana. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU).

Under the new policy, most asylum seekers are not being screened to determine if they would face persecution or torture in Mexico before being forced back. The administration claims it has instituted procedures to ensure that people who would face persecution or torture in Mexico are not returned there, but these procedures are egregiously inadequate. In fact, the administration contends that “Mexico will provide [asylum seekers who are sent back] with all appropriate humanitarian protections for the duration of their stay.”

But for John and the other asylum seekers caught up in this policy, their stays in Mexico present a very different reality.

The violence and instability that migrants and asylum seekers face on the Mexican side of the border is well-documented. In fact, the U.S. State Department lists “violence against migrants by government officers and organized criminal groups” as among the most significant human rights issues in Mexico.

Kevin, an evangelical leader in his church, fled Honduras after MS-13 threatened to kill him for preaching to his parish against the gang life. When he arrived in Tijuana, he sought shelter at a local church. The church workers warned him that migrants from Central America were being kidnapped by local gangs and held for ransom. While he waited for his number to be called so that he could seek asylum in the U.S., Kevin stayed close to the church, never going outside at night.

Dennis, a 20 year old, fled Honduras after MS-13 threatened to kill him. After weeks of waiting in Tijuana, he was able to enter the U.S. to seek asylum. U.S. immigration officials put him in a cell with 12 other men. "I felt lonely and desperate. I had never been in prison before," Dennis said. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

Christopher, a 39-year-old asylum seeker from Honduras, was robbed at gunpoint in Tijuana while walking to the store. On two separate occasions, he and other migrants were robbed and assaulted by a group of Mexicans, who attacked them with rocks.

While in Mexico, Howard, a 22 year old who fled Honduras after almost being killed by a drug cartel, was kidnapped by Los Zetas, one of Mexico’s most powerful drug cartels. He was held hostage for 15 days before managing to escape. What could have happened still haunts him — after the experience, he watched videos online of Los Zetas torturing people by putting them in barrels with a chemical that dissolves their bodies. To this day, he remains terrified that the gang will find him.

Despite these dangerous experiences in Mexico while they waited for their numbers to be called on the asylum list, all of these people were nonetheless sent back to Mexico shortly after being assigned a court date in the United States. Kevin, John, and Christopher, among others, were never even asked whether they were afraid to return.

And those who did attempt to explain why returning to Mexico would subject them to danger were ignored. In two interviews, Howard told officers about being kidnapped and his fears that he would be found by the people he had escaped. He was told that his statement would be analyzed to decide if he would be sent back. The next day, he was put into a van by Customs and Border Protection officers and told not to turn around. No one said where they were going, and Howard believed he was being taken to San Diego or another detention center. The next thing he knew, he was back in Mexico.

Howard wanted to refuse to go back but was afraid that he could be punished for speaking up. “I had already said many times that I was afraid to go back to Mexico, and nobody seemed to care,” he said.

When the asylum seekers were finally allowed to enter the U.S., they believed they would be staying there. Instead, they were returned to Tijuana in a matter of days. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

Similarly, when a CBP officer asked Ian, another asylum seeker, whether he could wait in Mexico until his asylum interview, Ian said no. Ian was also asked whether any other country had offered him asylum, and he again said no. At the end of their conversation, the officer had Ian initial and fingerprint several forms that were written in English, which he can’t read.

Ian spent all day in a frigid, small CBP holding cell known as an “icebox.” Later that night, he was called for a second interview. Most of the officer’s questions focused on Mexico, which surprised him. He thought he was going to be able to explain what had happened to him in Honduras, about his job as an undercover police officer, and how narco-traffickers had found out his identity and came looking for him. After he fled Honduras, the narco-traffickers murdered his brother.

“I feel like bait for a wolf.”

Instead, the CBP officer wanted to know why he didn’t want to live in Mexico. Ian explained that friends whom he had traveled with to Mexico had been killed there. Also, that while in Tijuana, he had been robbed and detained by the Mexican police. While he was speaking, the officer told him that he could only give short answers and shouldn’t talk for too long.

The next morning, Ian and a group of other asylum seekers were transported from San Ysidro back to Tijuana in handcuffs.

“Your Case Isn’t in the System”

For the asylum seekers forced to return to Mexico, everything feels dangerously in limbo. After so many weeks of waiting for their numbers to be called so that they could present themselves in the “right way,” it was distressing and frightening to be back in Mexico just a matter of days later.

They were sent back with many questions but little information. Before dropping them off in Mexico, CBP gave asylum seekers a few sheets of paper, which indicated their next court date in the United States and a list of organizations where they could try to get an attorney. All were located in the United States.

“No one explained how I could find an attorney or how an attorney in California would be able to represent me if I am in Mexico,” John said.

Christopher holds his visitor visa card and a slip of paper showing how many days he has until his next court hearing in the United States. Many asylum seekers report being told that these papers don't allow them to work, making surviving in Tijuana a challenge. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

After Maria, an asylum seeker from Guatemala was sent back to Tijuana, she tried to call the organizations on the paper for help. She was told that in order to get a lawyer, she would need to come to their offices in California, which of course was impossible. As of last week, she still didn’t have a lawyer.

Dennis, a 20-year-old Honduran asylum seeker, called the number listed on the form to reach the immigration court. It was an automated system — without a way to reach a person — and when he tried to check the status of his case, the voice said that his case was not in the system.

“I was told to present myself in El Chaparral on March 19, but I am not sure exactly where,” Dennis said. “I am afraid that I will miss my immigration court hearing.”

It was a fear echoed by many others, and for good reason. On March 14, it was reported that at least one asylum seeker missed their immigration court hearing because of what the government called “a glitch” in the scheduling system.

Her asylum hearing was unexpectedly moved up several days, and the court didn’t have a way to communicate the change. That day, fortunately, her lawyer was in the courtroom and explained that her client was currently at the U.S. port of entry, trying to get in, but CBP would not let her through.

Faced with this information, ICE’s chief counsel for the region asked the immigration judge to order the asylum seeker deported “in absentia,” as if she’d simply chosen not to show up at the hearing. Thankfully, the judge denied the motion. Critics of the new forced return policy have long argued that it will inevitably lead to in absentia orders of removal against asylum seekers who won’t receive notice of changes in their hearing dates.

“This Isn’t a Life”

The struggle is not limited to figuring out what will come next legally; there’s the question of how to simply survive in Tijuana.

The administration has justified its forced return policy by pointing to Mexico’s assurance that returned asylum seekers will have the right to live and work there. But the temporary visas that the Mexican government has provided to them do not authorize asylum seekers to actually work.

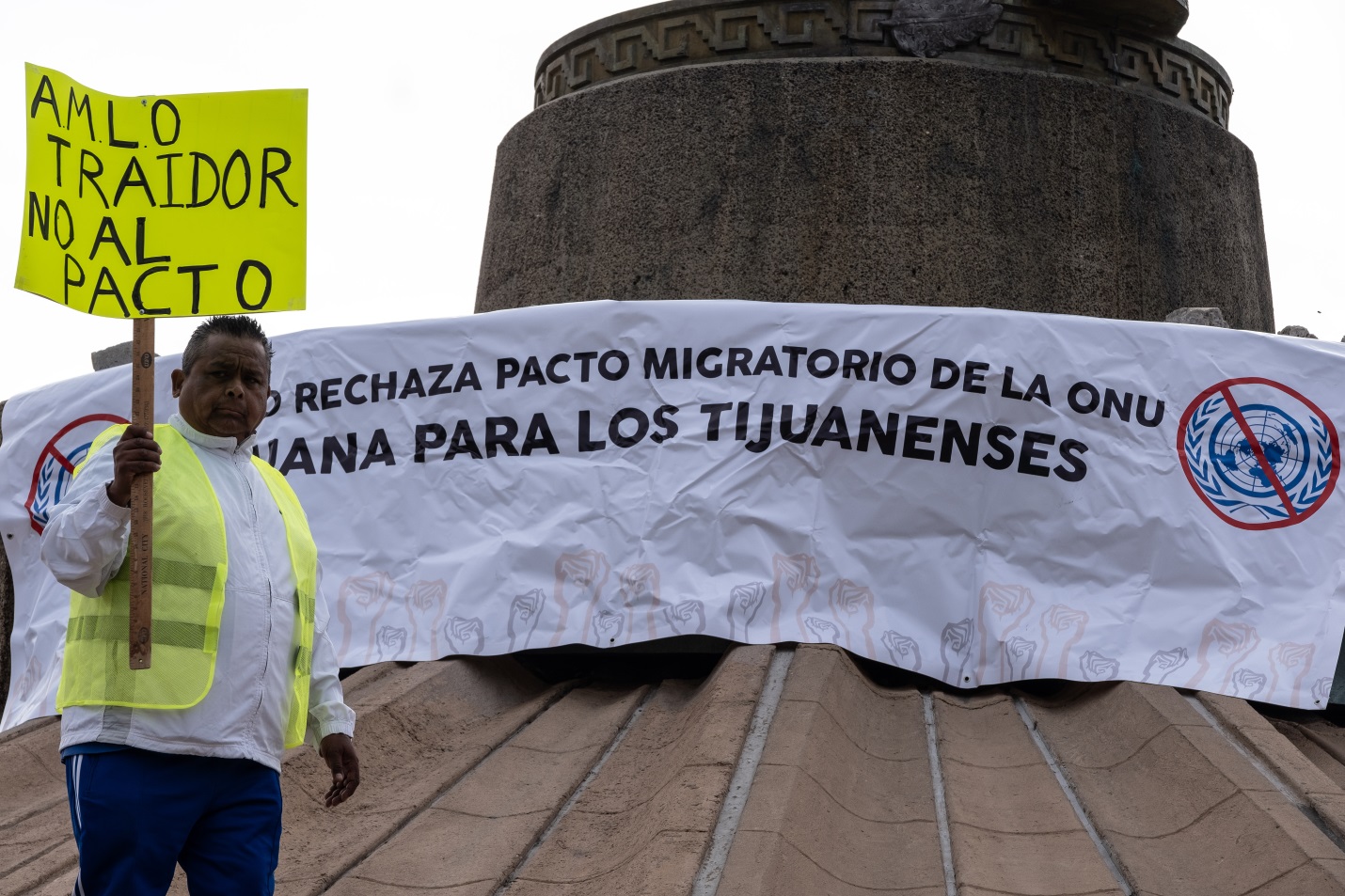

An anti-migrant demonstration in Tijuana on Sunday, March 10. The sign reads in part, "Tijuana for the Tijuanans." Tijuana has the highest homicide rate in Mexico, and Central American asylum seekers have become a target for violence. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

When John first arrived in Mexico, he was given a regional visitor card, an ID that allowed him to be in Mexico legally for one year. However, on Jan. 29, when he presented himself to be taken to the U.S. port for his asylum interviews, officers from Grupos Beta, an arm of Mexican immigration services took his ID card away.

The next day, when he was returned to Mexico, Grupos Beta did not give him another visa card. Instead, he received a piece of paper that a Grupos Beta officer told him would allow him to wait for his court date in Mexico, but it did not allow him to work.

Many of the ACLU’s clients reported the same thing upon being returned to Mexico.

Christopher is not sure whether he has the right to work. “But either way, I’m too afraid to work,” he says. He has heard stories about Mexican employers kidnapping Central American migrants and killing them or extorting their families for money. A few days after he was returned from the U.S., he was stopped by Mexican police who told him that he will be arrested if they see him on the street again. Since that day, he avoids going outside.

When Christopher first arrived to Tijuana, he slept in a tent made of blankets and became ill. "When it rained, everything got wet. I had to huddle together with other migrants to sleep. At one point rainwater rose up to my waist," he recalls. (Guillermo Arias/ACLU)

The asylum seekers are also terrified that at any time, they could be deported back to their home countries. If the worst should happen, Kevin has little faith that the Mexican government will help.

“The police have deported so many people. It seems like that’s just their policy, to deport migrants while they’re trying to seek asylum,” he said.

It takes Kevin two hours to get to the only legal office that he knows of in Tijuana. “I have to walk about half an hour from the bus stop to the church where I am staying and it is very dangerous. I feel like bait for a wolf.”

Without his visitor card, John also isn’t confident that he will be allowed to remain in Mexico until there is a decision in his U.S. asylum case.

He currently sleeps at a shelter in Tijuana, which requires everyone to leave the shelter between 6 a.m. and 3 p.m. The hours when he has to be outside are scary. At times, one of his neighbors has thrown rocks and water at him because he is Guatemalan.

Each day, he looks for temporary work that does not require formal documentation. Sometimes he is paid, and sometimes he is not. Often, he is paid only in food and there are days when he goes hungry.

“The circumstances I am in are very unfair,” he says, “I sought asylum in the United States. Tijuana is a very violent city for people like me.”