Matters of Principle

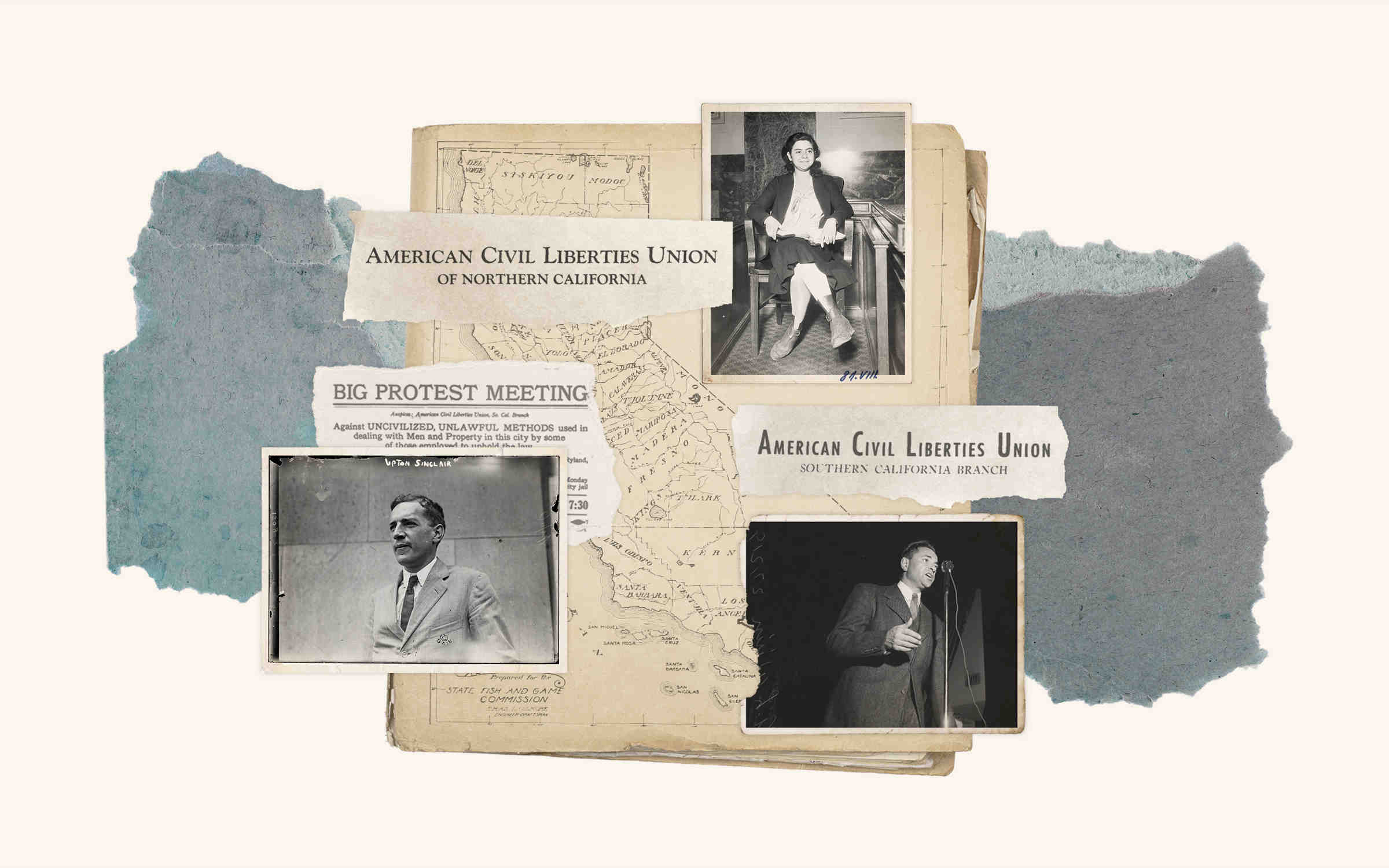

The novelist Upton Sinclair’s come-to-Jesus moment on civil liberties came during a strike in 1923 by longshoremen at the San Pedro Harbor in Los Angeles. Outraged that the Los Angeles police kept breaking up strikers’ outdoor meetings and throwing them in overcrowded jails, often on trumped-up charges, the 44-year-old writer hoped to use his stature as a public intellectual to protect the strikers’ free speech rights.

On May 15, 1923, Sinclair started at the mayor’s office and then proceeded to the office of the chief of police, Louis D. Oaks, seeking reassurances from both men that he would be allowed to read from the Bill of Rights on Liberty Hill, a piece of private property overlooking the waterfront where some strikers had been meeting with the consent of the owner. Even though Mayor George E. Cryer of Los Angeles had already assured Sinclair and what Oaks called his fellow “Pasadena millionaires” that they’d be allowed to meet provided they did not “incite disorder,” Oaks threatened them with arrest, jail, and “no bail” if they tried it. Sinclair hoped for a technical arrest that would facilitate a test case. Oaks would not oblige him, leaving Sinclair and company no other choice but to march up Liberty Hill and begin reading the Bill of Rights. Sinclair was partway through the First Amendment when he was arrested.

Upton Sinclair (center) in New York City in 1914.

Library of Congress

Sinclair likened what happened next to an “old-style . . . melodrama.” He and the other speakers were stuffed into a police car and driven around for quite some time, ostensibly to evade the press, before finally ending up at the jail in nearby Wilmington. There the local police captain told them they had “forfeit[ed] your constitutional rights” by “encouraging . . . revolution,” a claim he backed up by denying them access to their attorneys. They spent the night there, Sinclair avoiding the lice-ridden cot in his cell by sleeping on the cold, hard floor.

By the time they were transferred to the Los Angeles County Jail, police court had conveniently just closed, prolonging their stay. In the end, his “unpleasant” experience — as his friend, the poet George Sterling, put it — and the fact that the district attorney dismissed the case against him persuaded Sinclair that he could better serve the cause of civil liberties by financing the launch of the ACLU’s first affiliate, the Southern California Civil Liberties Union. Like its champion, the organization Sinclair helped to fund was fierce, determined, and attuned to local civil liberties matters. It was also imbued with a distinctively California ethos, independent and, at times, improvisational in ways that made some of the national ACLU’s first leaders uncomfortable.

‘Paddling Our Own Canoe’

Thanks to Sinclair and the money he donated to hire its first director, the Southern California affiliate flourished immediately. In 1926, Austin Lewis of San Francisco briefly formed a northern California affiliate there to work with the Southern California group for the repeal of the state’s criminal syndicalism law. Although that group didn’t last, Lewis continued to muster San Franciscans as needed, once lecturing ACLU Executive Director Roger Baldwin that his interference in matters best left to Californians “had worked enormous harm.”

That kind of confidence made the Easterners who ran the national ACLU pay attention, while the Californians’ effective approach to local civil liberties matters forced the national leadership to be more accommodating, perhaps, than they wanted to be. We forget now 100 years out that the early ACLU was an improvisation, shaped only by its founders’ commitment to individual civil liberties. Those in the West helped form a more perfect national American Civil Liberties Union.

The early national ACLU ran on a shoestring, organized by people with national stature. They relied on the classic organizational structure of a director and a board in New York City while giving Baldwin a lot of latitude to handle daily business. It worked because everybody knew and trusted everybody else. Their shared endeavor rested on the odd combination of privilege, challenge, and old-school ties.

Civil libertarian circles were small in the 1920s. If a case arose outside of New York, Baldwin made a call, found an attorney, and got it worked out. Occasionally in the 1920s, a group of local people would react to a local matter by forming an affiliate that would usually fade once the issue resolved. What the Southern California ACLU had that these other groups lacked was an executive director, whose salary Sinclair paid for one year. The first Los Angeles director, the Rev. Clinton J. Taft, was well-placed to continue raising the funds needed to make the group self-sufficient thereafter, with the benefit of a donor list that included Sinclair, Charlie Chaplin, the razor manufacturer King C. Gillette, and the sugar magnate Rudolph Spreckels.

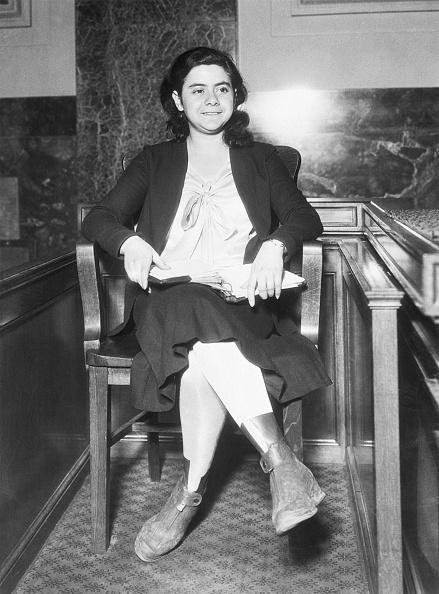

Yetta Stromberg. February 21, 1931

Getty/Bettman

Read Reverend Taft's letter to Roger Baldwin from March 1924

The Southern California branch gained national prominence when its attorneys successfully challenged a California statute that outlawed the display of radical symbols like red flags in Stromberg v. California at the Supreme Court. In 1929, 19-year-old Yetta Stromberg was convicted of using a red flag in a youth camp ceremony. In its ruling, the Supreme Court held that the law was “vague and indefinite” and could be used to violate the First Amendment. The decision was among the first to protect nonverbal speech and symbolic expression.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Throughout the 1920s, California’s civil libertarians, as one local leader noted, were happy “paddling our own canoe,” building a local organization at once capable and invisible outside the state. That changed in the 1930s. The Depression raised the ACLU’s profile and expanded its workload, which changed the very loose relationship between Los Angeles and New York.

ACLU on the Bay

Meanwhile, in 1934, Austin Lewis successfully mustered the Northern California affiliate on a more permanent basis. Like the Southern California affiliate, it seemed potentially mutinous and costly once Baldwin started to pay attention. Activists in both California groups tended to skip the “formalities” of checking in with the national organization before acting, naively assuming the New York office could and would cover their expenses.

Still, the Southern California affiliate had cachet, and Baldwin favored it over the Northern California affiliate. The Stromberg case demonstrated the Angelinos’ mettle. San Franciscans, though, frustrated him, particularly the first paid Northern California executive director, Ernest Besig, who replaced Lewis in 1935. Besig had gotten his start in the Southern California ACLU, venturing north to help with a case at the behest of Southern California, and then staying.

Besig was uncompromising and stubborn as well as principled and dedicated, qualities that Baldwin also possessed, which made for a rough relationship. Besig wanted the status of the national ACLU — plus some of their letterhead stationery and a little start-up money — but also complete autonomy. He was very good at attracting local people to the cause and holding their loyalty, although few of them paid dues to the national ACLU. Baldwin had “an extreme lack of confidence” in Besig, or so Besig complained, even though he quickly and successfully built up the Northern California branch.

Yet Southern California seemed only slightly more tractable. As Communist organizers moved into the Central Valley in 1930 to try to organize migrant farm workers, Southern California Executive Director Clinton Taft and staff attorney Leo Gallagher followed, bailing out organizers and battling thugs and local sheriffs. Expecting praise for heroically, as Gallagher put it, “working for civil liberties,” they were surprised when Baldwin chastised them for failing to get bail receipts.

Filipino migrant laborers harvesting lettuce in the Imperial Valley in 1939.

Library of Congress

When Gallagher’s law partner and fellow Southern California ACLU attorney, A.L. Wirin, telegrammed Baldwin from New Mexico saying that he was prepared to open a satellite office and could he please send money, Baldwin curtly rejected the idea.

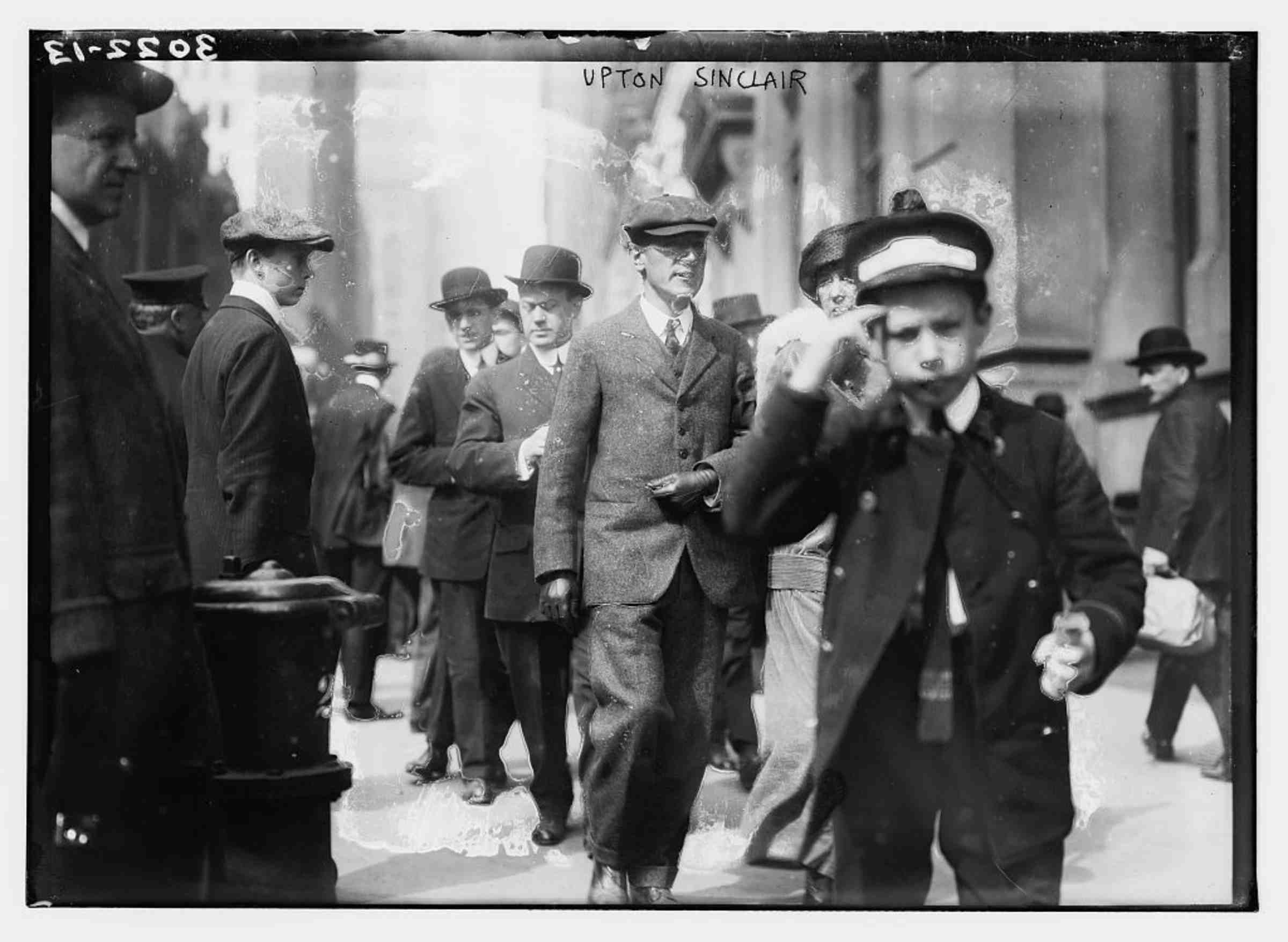

A.L. Wirin speaks to striking workers ca. 1942.

Neg. # 27219-1, Los Angeles Daily News Negatives (Collection 1387). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library

Several years later, Wirin and Besig returned to the Imperial Valley and were beaten and run out of town by local vigilantes for trying to protect union organizers’ rights to speak. An exasperated Baldwin told them to stop the drama and please work through New Deal agencies. Reading those exchanges, you can practically hear the Angelinos begging to be praised for their hard and dangerous work and imagine Baldwin’s eye rolls at the thought of some meddling Californians upsetting his organization.

For Baldwin, at least Besig wasn’t a Communist, which wasn’t true where the Southern Californians were concerned. In several instances, including in the Stromberg case, the Southern California branch partnered with the Communists’ International Labor Defense. Gallagher was likely a party member. Initially, nobody cared. As the New York intellectual community divided into pro and anti-Communist factions, though, ACLU board meetings no longer had that comfortable sense of shared endeavor and colleagues who saw eye-to-eye. Californians living in a different milieu might have been aware of the emergence of liberal anti-communism, but they paid little attention to it.

Eventually, however, they were sucked into the internal conflict. In February 1940, the national board narrowly passed a resolution declaring it “inappropriate” for anyone in a leadership position in the ACLU to belong to a “totalitarian” organization and removed from its ranks its one public communist, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Some unhappy board members contacted the affiliates, confident of at least stirring up some trouble.

And they did.

Both California affiliates led an effort to get the resolution rescinded, outraged that a “tiny New York group” got to determine a policy with such potentially far-reaching consequences. Baldwin’s assurances “that policies are pretty democratically determined by a board of 35 members meeting weekly in New York” failed to assuage them.

Arrangements between affiliates and the national organization had not been very well established. Until that point, most disputes involved money the affiliates wanted from the national organization and the handling of local matters. As new people came on to the national board and the times and issues changed, the board proceeded more cautiously, trying to forge compromises and establish policies. The branches felt excluded, but bound by those decisions. In 1941, Baldwin and the board finally regularized affiliate policies. Local groups were to handle local issues and could “express their view[s] . . . without legal force” on national ones.

America Goes McCarthyite

The tension between the independent and more politically radical California affiliates and the national ACLU, as well as their demand for a greater voice in national policy, remained evident as America descended into the McCarthy era. In response, Baldwin promised to “consult” with them in the future before establishing policy.

But was that promise sincere? Most California activists doubted it.

The post-war board had more anti-communists on it, who made liberals uneasy about defining communism as a threat to American democracy, especially given the climate of the times. The late 1940s were a moment of growing anti-communism expressed as fears that the Soviet Union had infiltrated U.S. institutions and was using members of the American Communist Party as spies and instigators of revolution. A number of disillusioned radicals sat on the ACLU board, angry, uncompromising, and absolutely determined to stop communists from using free speech claims to advance their totalitarian ideals.

Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.) appearing on a nationwide radio program with Fulton Lewis Jr., left.

Associated Press)

The anti-communists resisted compromises while national board liberals struggled to keep the organization both on course and uncompromised in any witch hunt. Since neither side trusted the other and the board was pretty evenly split, the most logical way forward seemed to create policy statements that spelled out the ACLU’s position on matters like loyalty programs for government employees, including teachers. The national staff, however, somehow failed to consult the affiliates before releasing a much-debated policy statement on loyalty investigations.

Besig thundered his outrage, both over the statement and the process. Perhaps channeling his inner Upton Sinclair, A.A. Heist, the new executive director of the Southern California affiliate, decided in 1948 to take the bull by the horns and challenge the national ACLU to “change our whole set-up.”

Read the ACLU Statement on Loyalty Tests for Federal Employment

Baldwin dismissed that idea as unthinkable, but Heist and Besig reached out to their counterparts across the country. Affiliate representatives arrived at the 1949 ACLU convention ready for a fight. Once again the board stonewalled them with the promise of “an effective voice,” yet what they actually got — more promises for consultation — did “not meet . . . the need for effective representation.”

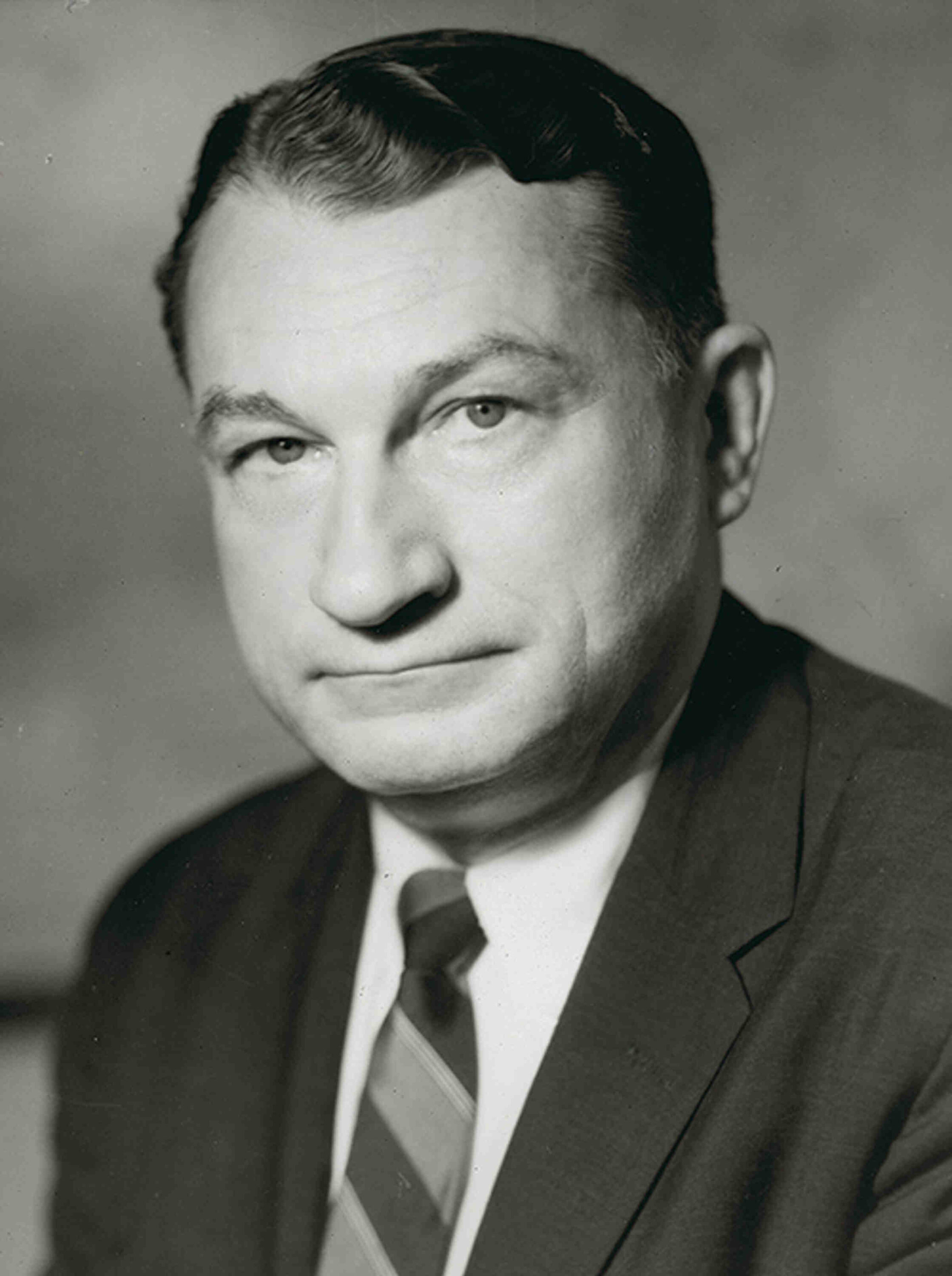

ACLU Executive Director Patrick Murphy Malin

Date and photographer unknown

Delegates from several affiliates met on their own in Des Moines in January 1950 and developed several counterproposals. By then Baldwin had retired as director and his replacement, Patrick Malin, was less wedded to the old-style ACLU. In April, the national board approved significant changes to the organization’s governance, based on suggestions arising out of the affiliates’ Des Moines meeting. These changes explicitly enshrined affiliates’ right to vote in policy matters, giving them a minority voting percentage — a new mechanism to make their voices heard by the national board.

Which leads us to the events of 1953-1954, perhaps the peak of McCarthyism nationally. After some desperate anti-communist board members succeeded in barely passing three anti-communist policy statements, affiliates found themselves in a position to influence the outcome of something. Yet there were disputed vote tallies regarding the policy statements. A “struggle for the soul of the ACLU” ensued, historian Samuel Walker suggests, with months of arguments, measures, counter-measures, meetings, and, finally, resolution.

The most difficult partisans left the board, the policy statements disappeared, and still more equitable power sharing followed. Besig kept his affiliate independent during his tenure, but after his retirement, Northern California would become financially integrated into the national organization during the early 1970s.

The rebels and innovators in California were individuals perfectly suited to advocate for constitutional freedoms, but perhaps imperfectly suited to an increasingly bureaucratic organization. Their struggles to fit into a national structure created a more complicated ACLU — and ultimately helped build a more powerful institution.

Judy Kutulas is the Boldt Distinguished Teaching Chair in the Humanities and Professor of History at St. Olaf College in Northfield Minnesota. She is the author of The American Civil Liberties Union and the Making of Modern Liberalism, 1930-1960 (University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

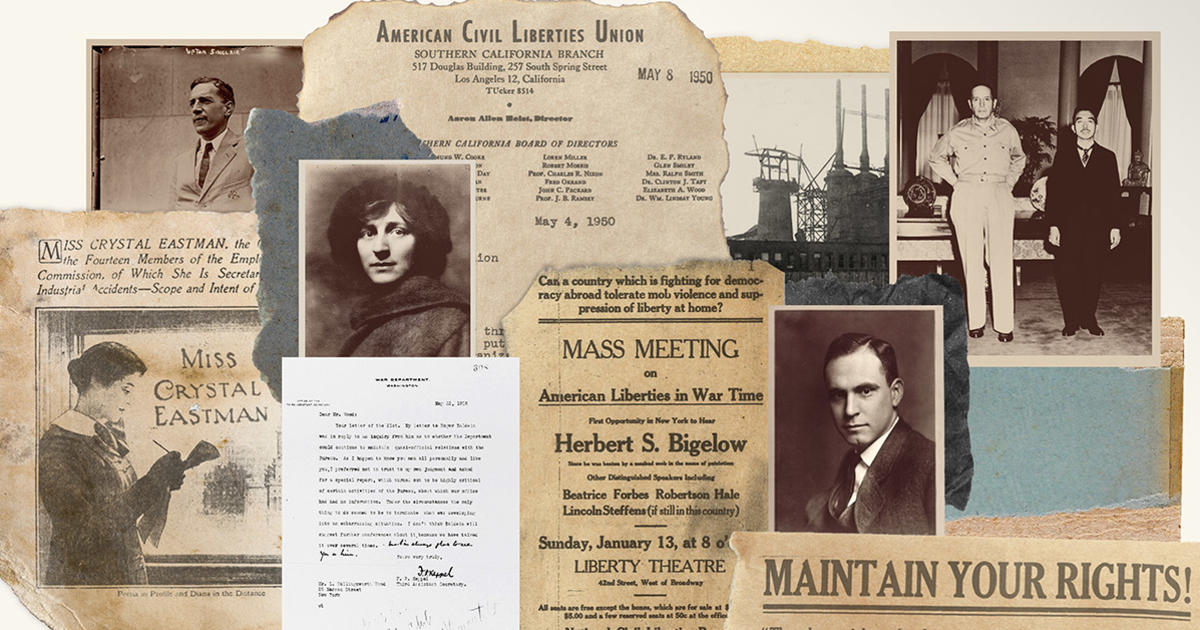

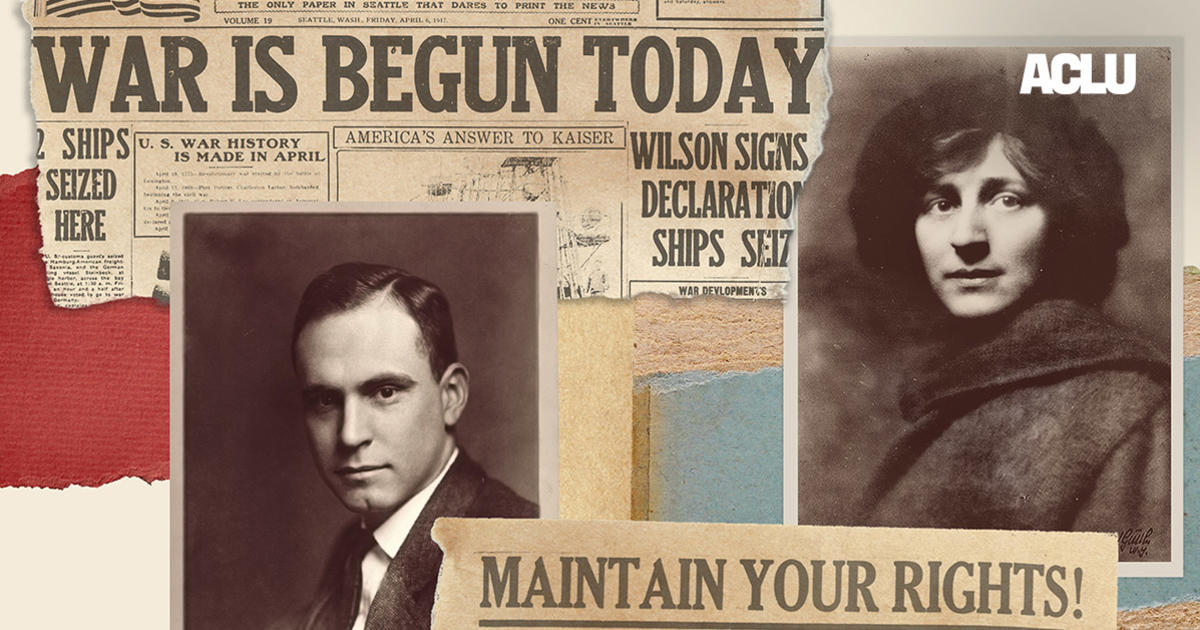

Crystal Eastman, the ACLU’s Underappreciated Founding Mother

A preeminent organizer of her day, Eastman was a fierce champion of most of the major movements for social change in the early 20th century.

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Conscientious Objectors

The ACLU was born out of World War I and the repression that resulted when the U.S. joined the fight.

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Donate to the ACLU

The ACLU has been at the center of nearly every major civil liberties battle in the U.S. for more than 100 years. This vital work depends on the support of ACLU members in all 50 states and beyond.

We need you with us to keep fighting — donate today.

Contributions to the ACLU are not tax deductible.