I Fought the Imperial Presidency, and the Imperial Presidency Won

When I became the assistant legal director at ACLU national headquarters in 1972, I spent much of my time fighting the growth of the Imperial Presidency. Donald Trump isn’t the first president to trample on the separation of powers. He’s just the latest symptom of a much more dangerous disease.

In 1952, Harry Truman tried to seize the nation’s steel mills unilaterally during the Korean War to forestall a strike. The Supreme Court stopped him. Richard Nixon’s effort to govern alone eventually backfired, and he was forced to resign in 1974. But, alas, no one stopped JFK and LBJ when they unilaterally took us into the Vietnam War without congressional authorization — an unconstitutional war that Congress never formally authorized in which almost 60,000 American service members, 250,000 Vietnamese soldiers, and more than 2 million Asian civilians would die as U.S. forces dropped more bombs on Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia than all the belligerents combined during World War II.

Smoke rises from bombs dropped by U.S. planes near the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, July 25, 1973.

AP Photo

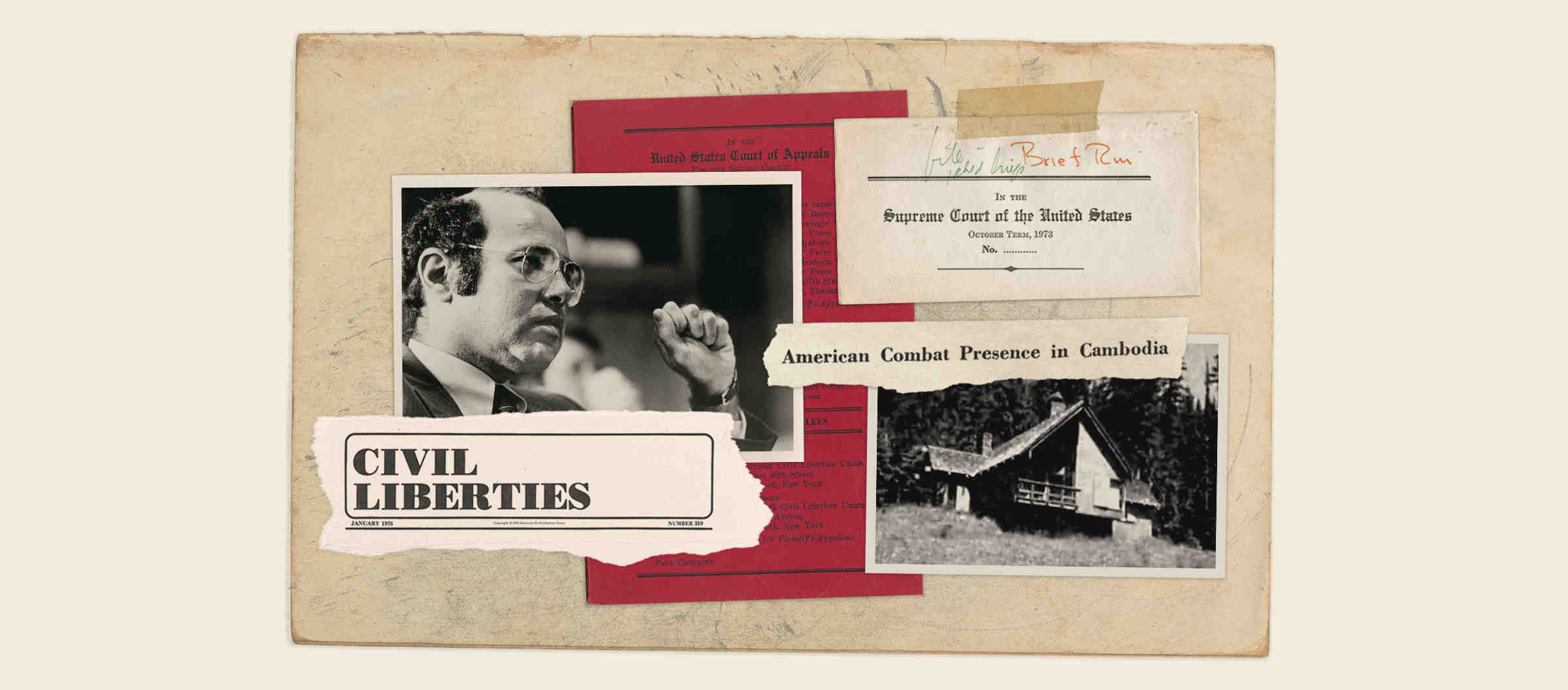

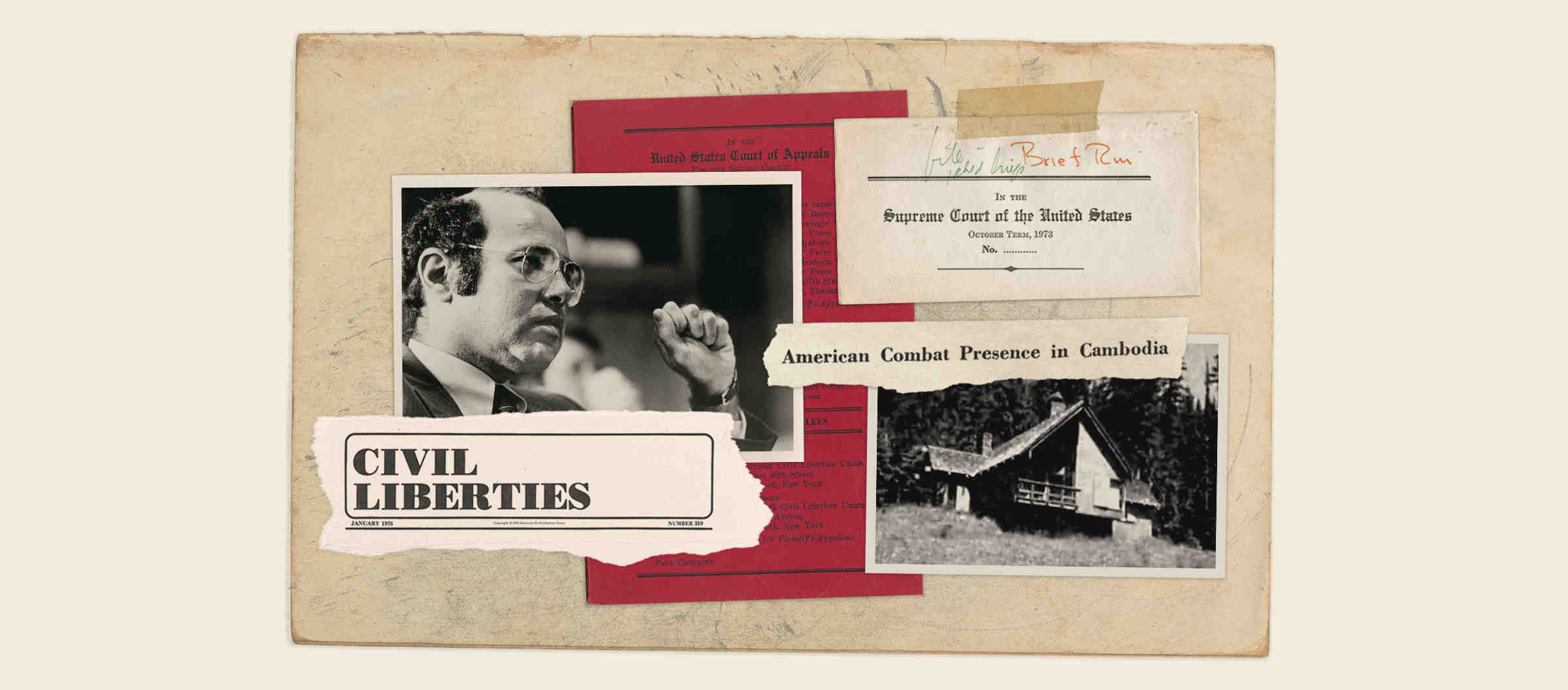

Driven by the illegality and murderous injustice of the war, I flew across the country and drove all night in the summer of 1973 to ask Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas to stop the unconstitutional bombing of Cambodia, secretly ordered by President Nixon in April 1970. It was the last gasp in the ACLU’s sustained effort to enforce Congress’s exclusive power to declare war. I owe a special debt in the Vietnam War cases to my long-time colleague and mentor at NYU and the ACLU, Norman Dorsen, who was already a respected academic in those days, as well as an ACLU general counsel. Norman agreed to lend his analytic precision and academic prestige to the Second Circuit argument in DaCosta v. Laird, an early effort to challenge the war’s constitutionality. In the course of a brilliant 45-minute oral presentation, Norman turned a fringe theory into a credible legal argument. He also persuaded me that it was possible to link an activist life in court with a career as a law professor.

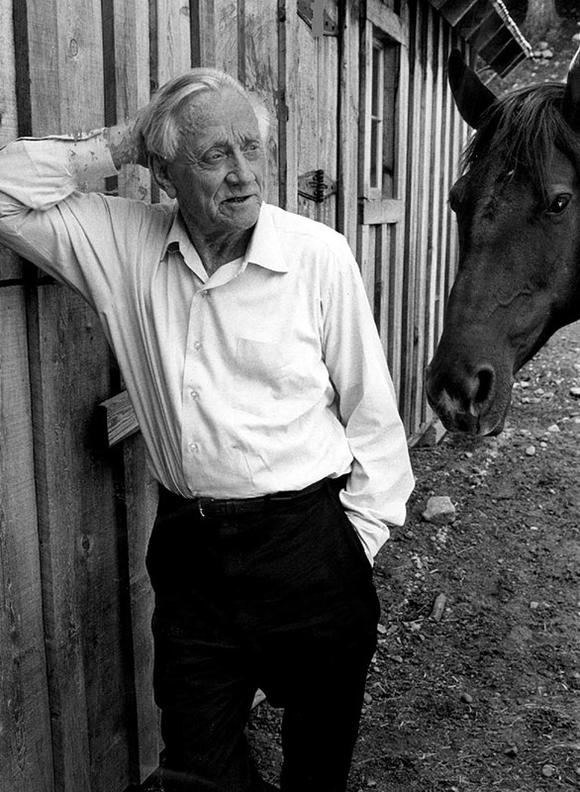

The author, Burt Neuborne, 1983.

Lawrence Frank

An Unconstitutional War

Once Norman had rendered the arguments respectable, Leon Friedman and I peppered the courts with constitutional challenges to the Vietnam War. Every expansion of the country’s military presence in Vietnam, like the mining of Haiphong Harbor, triggered a new constitutional challenge. We zeroed in on two extraordinarily decent and conscientious Brooklyn federal judges, Orrin Judd and John Dooling, arguing that neither the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, nor routine votes on military appropriations, were constitutionally adequate Congressional authorizations for a full-scale war.

The Brooklyn judges were clearly uncomfortable. One afternoon, Judge Dooling interrupted my argument in the Haiphong Harbor case and called me to the bench. I expected a verbal spanking for some gaffe.

Instead, Judge Dooling said: “Mr. Neuborne, you seem to be having a very good time arguing this case. I’m not having much fun judging it. How about changing places?”

I told him: “Not on your life, your honor. I have the easy job. The tough job is yours. Please do it.”

We lost again.

Finally, Judge Judd bit the bullet — literally — in a case challenging the carpet bombing of Cambodia. Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman of Brooklyn, New York, and a group of Air Force bomber pilots stationed at the Utapao Air Force base in Thailand sought a judicial ruling that the bombing of Cambodia was unconstitutional because it was unauthorized by Congress. On July 25, 1973, in a deceptively simple opinion, federal Judge Orin Judd of the Eastern District of New York ruled that Congress had not only failed to authorize the bombing of Cambodia, it had forbidden it. Judge Judd issued an injunction prohibiting the unauthorized bombing — the first and only time a federal district judge enforced the War Powers Clause of the Constitution. This was an act of courage and wisdom that deserves to be remembered.

Congress had not only failed to authorize the bombing of Cambodia, it had forbidden it.

Once Judge Judd had issued his injunction, the Holtzman case careened wildly through the appellate courts. Judd delayed his order for a day or two to permit the government to seek appellate review. On July 27, the Second Circuit Appeals Court in Manhattan issued an order allowing the bombing to continue pending a speedy appeal. Since the Supreme Court had adjourned for the summer, I flew to Washington, D.C, and asked Justice Thurgood Marshall to reinstate the injunction pending appeal. On August 1, after hearing several hours of argument in his Supreme Court chambers, Marshall explained that while he agreed with Judge Judd’s opinion, since the Supreme Court was in summer recess, he felt obliged to act as a surrogate for the full court, predicting how his absent colleagues would probably vote.

Marshall told me that he believed that the vote would be close, but that a majority of the court would probably dismiss the case as beyond the power of the judiciary. I argued bitterly with Justice Marshall — whom I revered — but could not persuade him that he was free to vote his own beliefs. Marshall finally told me, with some exasperation, that he had heard enough. He issued an order denying the request to reinstate the injunction but urging the Second Circuit to further expedite the appeal.

Thurgood Marshall in the White House, June 1967, the year he was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Yoichi Okamoto/National Archives and Records Administration

I still remember how angry I was at Justice Marshall for what I perceived as undue timidity. As the years have gone on, I have come to realize that his insistence on respecting the views of his Supreme Court colleagues was one of the great acts of judicial principle that I have ever witnessed.

A Cross-Country Hail Mary

Disappointed, I left Marshall’s Supreme Court chambers and called the “Douglas desk” at the ACLU. In those days, the ACLU kept a 24-hour watch on the whereabouts of Justice William O. Douglas, in case an emergency vote was needed to slay a dragon, square a circle, or stay an execution. Douglas — the first commissioner of the Securities and Exchange Commission, FDR’s first-choice for vice president in 1944 (Democratic Party leaders insisted on Harry Truman), the leading counter-weight to Joe McCarthy during the 1950s, among the greatest defenders of free speech in the Supreme Court’s history, and a passionate friend of the environment (Douglas once ruled that trees had standing to protect themselves) — was my best chance at reinstating Judd’s injunction.

Under the Supreme Court’s rules, there was still enough daylight to play another inning.

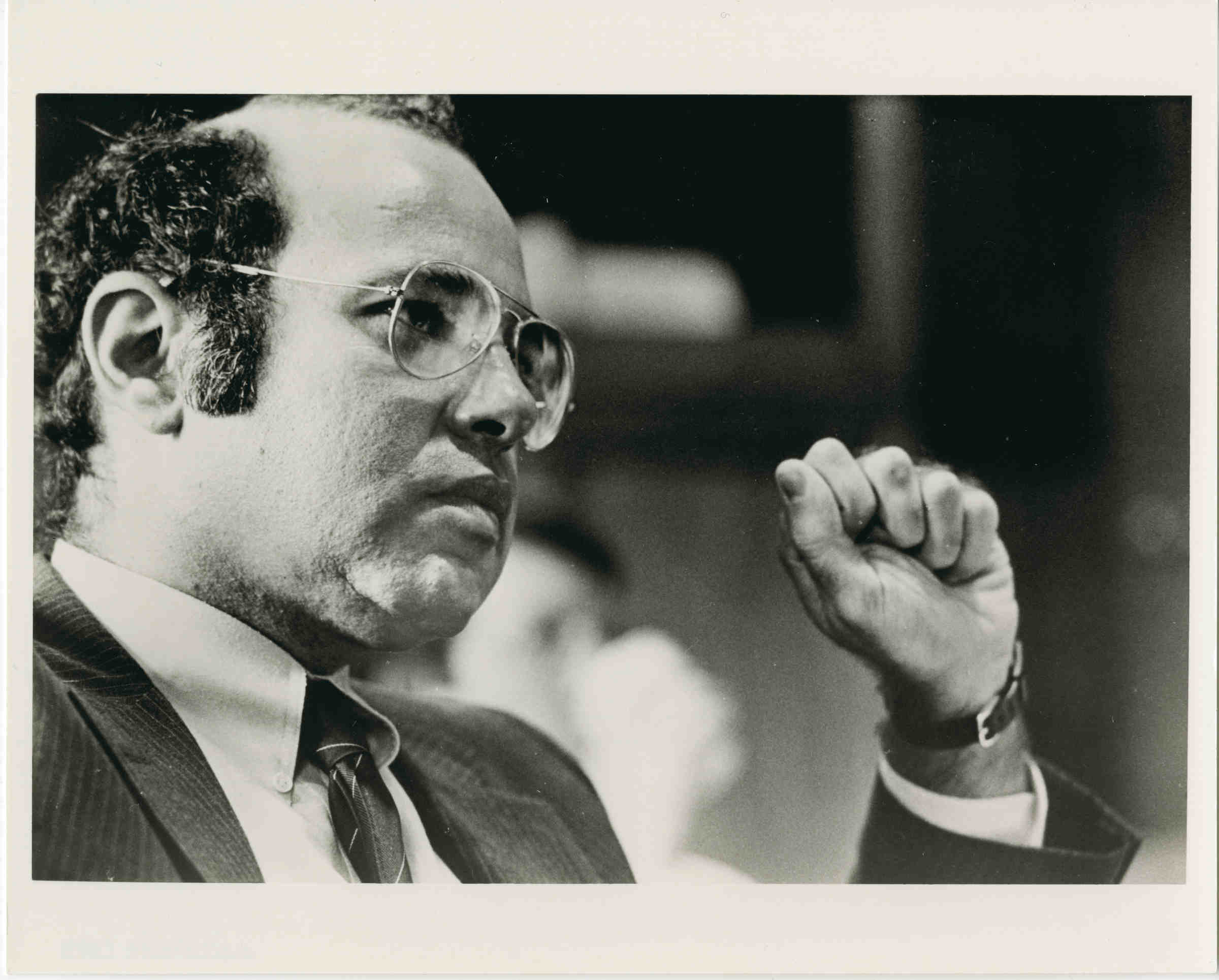

Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas in Yakima, WA, in 1973.

CBS Television

The voice at the Douglas desk confirmed that Douglas and his newly married wife, Cathy, were relaxing at his summer camp in Goose Prairie in the hills above Yakima, Washington. Actually, “camp” is too generous a word. Douglas called it a “camp.” It was really a shack. I jumped on the next flight to Portland, Oregon, rented a car in the Portland airport, and drove all night to Yakima, hoping that Justice Douglas would reinstate the injunction.

Norman Siegel, then a young ACLU intern who would later become the executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, had flown out the day before to help set up the potential argument in case I couldn’t persuade Marshall. He arrived at Douglas’s summer camp in Goose Prairie early in the morning and knocked on the door. An unshaven Douglas answered in his bathrobe, telling Norman to leave the papers and come back a couple of hours later.

When Norman returned after wandering in the woods for a while, Justice Douglas was gone. He was out hiking. But he had left a hand-written order nailed to a tree next to his cabin scheduling an oral argument at the Yakima Post Office for the next morning. When Norman showed the order to the local postmaster, the postmaster smiled and said: “Don’t worry. The justice does that all the time.”

I arrived in Yakima in time for the oral argument. A large crowd of people had quietly assembled around the post office after the news of the proceeding was reported by the local newspaper. They had come to pay homage to Douglas, who was nearing the end of his 36-year tenure on the Supreme Court and who would soon suffer a debilitating stroke. A complicated man, Douglas married four times, feuded acerbically with several of his colleagues, and was less than beloved by many of his law clerks. But he was revered by many as one of the greatest defenders of freedom in the nation’s history.

A frail figure in a dark blue suit that had grown much too big for him, Douglas arrived at the post office in a jeep accompanied by his wife, Cathy, a recent law school graduate who was studying for the D.C. bar. I began my oral argument only to be interrupted immediately by Douglas, who asked sharply: “Mr. Neuborne, what happened 20 years ago?”

I froze, turned pale, and managed to croak: “Mr. Justice Douglas, you said there’d be no math on this test.”

Douglas smiled and said a little less sternly: “No, I’m serious, what happened 20 years ago?” Then it hit me. “The Rosenbergs?”

Twenty years earlier, in June 1953, Douglas had stayed the executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, only to be quickly overridden by the full Supreme Court.

“That’s right,” Douglas answered gruffly. “Just remember it.”

The justice was trying to signal to me not to get too excited about his prospective ruling. I was confident, though, that the full court could not overrule Douglas this time around because Justice Marshall had told me the day before that a quorum of six justices was not present in Washington. I was confident (too confident, it turned out) that it would take a vote of a quorum of the court in a formal sitting to overturn any order that Justice Douglas might issue.

After an intense morning of oral argument — the United States was represented by the then-attorney general of Washington, Slade Gorton, because it was impossible to fly someone out from the Justice Department in time — Justice Douglas caustically told me to go home and not to reappear on his doorstep again. I promised to leave him alone.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

While we were in the air en route to New York, Douglas reinstated Judge Judd’s injunction, once again stopping the bombing. He reasoned that it was a matter of life and death, and that the law favored the pilots. Newspaper reporters shouted the news to me as I left the plane at Kennedy Airport. I was euphoric. But I should have paid more attention to Douglas’ warning about the Rosenbergs.

Douglas’ order stopping the bombing, like his stay of the Rosenberg execution, lasted just one day. As he had predicted, the government immediately sought to overturn his order. Justice Marshall reinstated the stay the next afternoon, claiming that he was not overruling Douglas, but merely staying Judge Judd’s order himself. Marshall added that he had polled the other seven justices serially by phone, and that the other seven agreed with him. By then, I was absolutely certain that Justice Marshall was carrying this collegial thing too far.

Douglas was furious, issuing a famous dissent bitterly charging that a serial telephone poll was not the equivalent of a quorum, which he insisted required the possibility of face-to-face discussion. He was right, of course. The Supreme Court has never done anything like it again, but the damage was done.

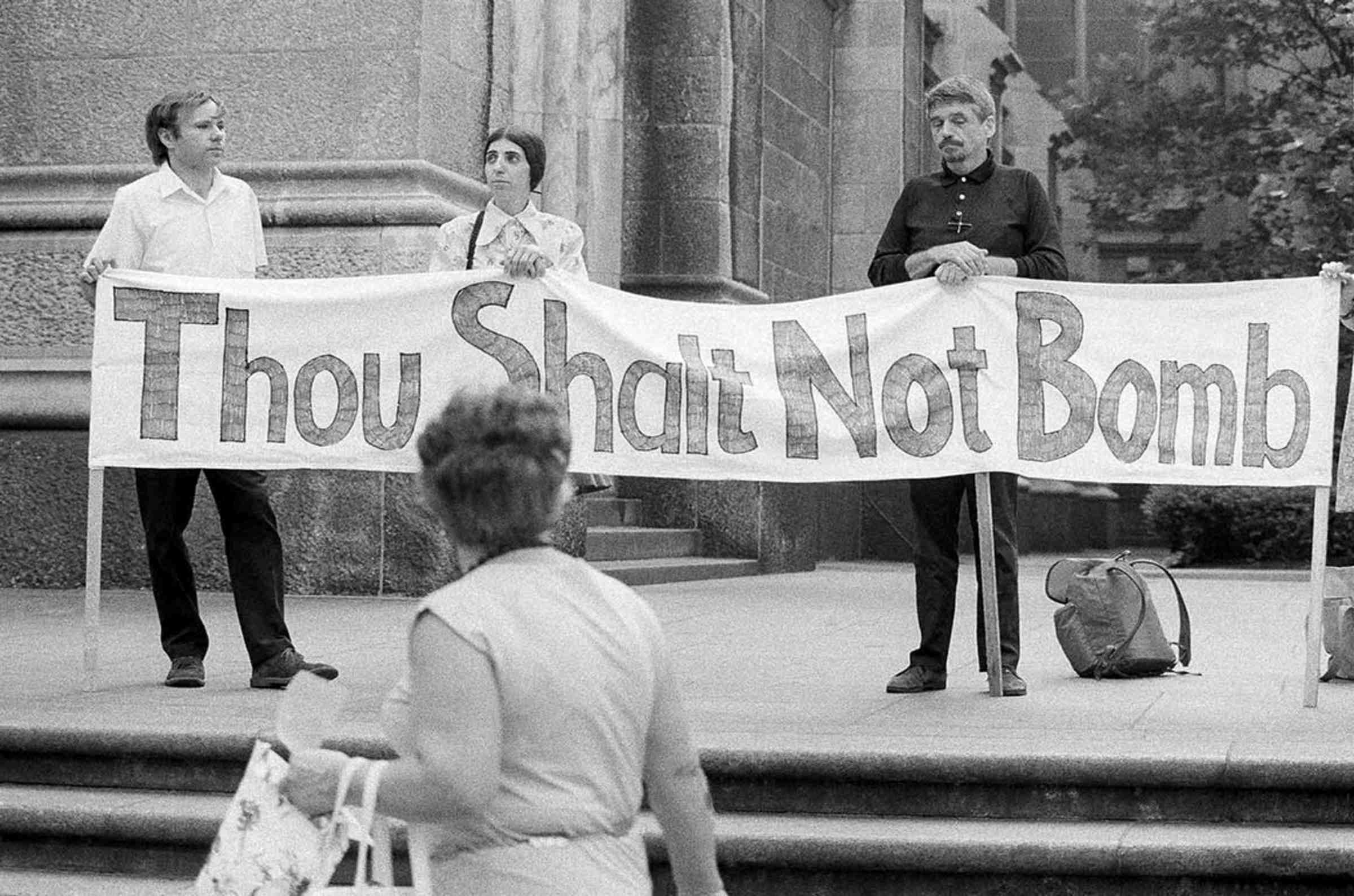

Rev. Fr. Daniel Berrigan and some friends participating in a fast and vigil to protest the bombing in Cambodia in New York City on July 25, 1973. That same day, Judge Orrin Judd issued an injunction prohibiting the unauthorized bombing.

AP Photo/Ron Frehm

Four days later, we argued the appeal from Judge Judd’s injunction in the Second Circuit before an emergency three-judge panel. Believe it or not, once argument began in the stuffy Second Circuit chamber, one of the elderly judges actually appeared to doze on the bench. As I feared, the three-judge panel reversed Judge Judd by a vote of 2-1. I briefly considered challenging the decision on the basis of one judge’s having fallen asleep but decided that it was “harmless error.” The sleeping judge would have done exactly the same thing — maybe worse — if he had stayed awake.

Judge James Oakes dissented, voting to uphold Judge Judd’s injunction and warning of the dangers of a runaway president bent on unilateral war-making. (Sound familiar? If only we had listened to him.) At that point, six judges had passed judgment on the case. Four of them — Judd, Marshall, Douglas, and Oakes — believed the bombing of Cambodia was unconstitutional and that the courts had a duty to enforce the Constitution. Two judges, Mulligan and Timbers, insisted that they lacked power to decide the question. So we lost 2-4, with not a single judge actually upholding the lawfulness of the president’s actions.

We appealed to the full Supreme Court, where the case ended with a whimper. As Justice Marshall had predicted, the full court declined review, in part because the government had made sure that Supreme Court review was no longer necessary.

By the time the Supreme Court had reconvened in October to consider the appeal papers, the Air Force had honorably discharged the dissenting pilots without court-martialing them, the Pentagon had stopped bombing Cambodia, and Congress was in the process of passing the War Powers Act of 1973, limiting the president’s unilateral authority to commit American troops to combat.

So, while the brave dissenting Air Force pilots who were my clients were spared court martial, and while Congress was goaded into making a start at controlling presidential war-making, we failed to make much of a legal dent in the Imperial Presidency. We’re refighting that battle today.

Burt Neuborne is the Norman Dorsen Professor of Civil Liberties at NYU Law School. He spent 11 years on the ACLU legal staff, beginning in 1967 as a staff counsel at NYCLU, and serving from 1981-86 as ACLU National Legal Director. In 1995, he co-founded the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU and served as its founding legal director until 2007. His new book, "When at Times the Mob is Swayed" (The New Press 2019), asks whether American institutions are strong enough to withstand Trumpist appeals to divisiveness, xenophobia, and misogyny.

Donate to the ACLU

The ACLU has been at the center of nearly every major civil liberties battle in the U.S. for more than 100 years. This vital work depends on the support of ACLU members in all 50 states and beyond.

We need you with us to keep fighting — donate today.

Contributions to the ACLU are not tax deductible.