Prosecutors Have the Power to Stop Bad Roadside Drug Tests From Ruining People’s Lives

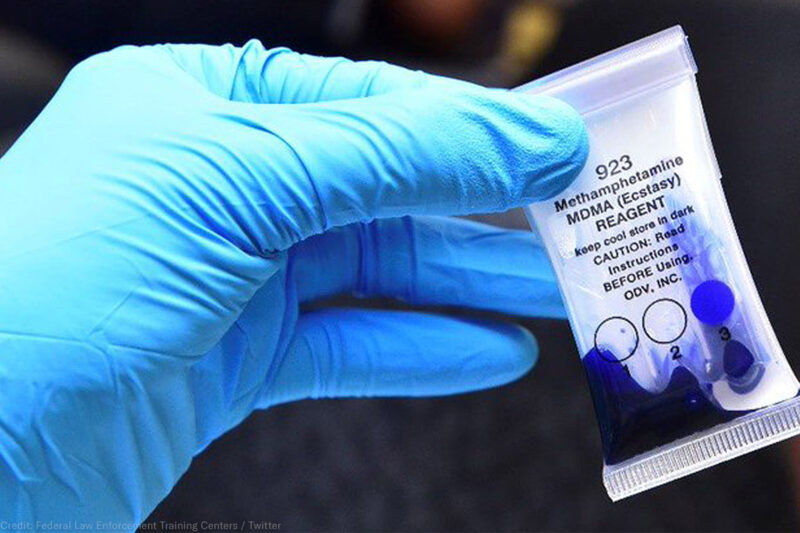

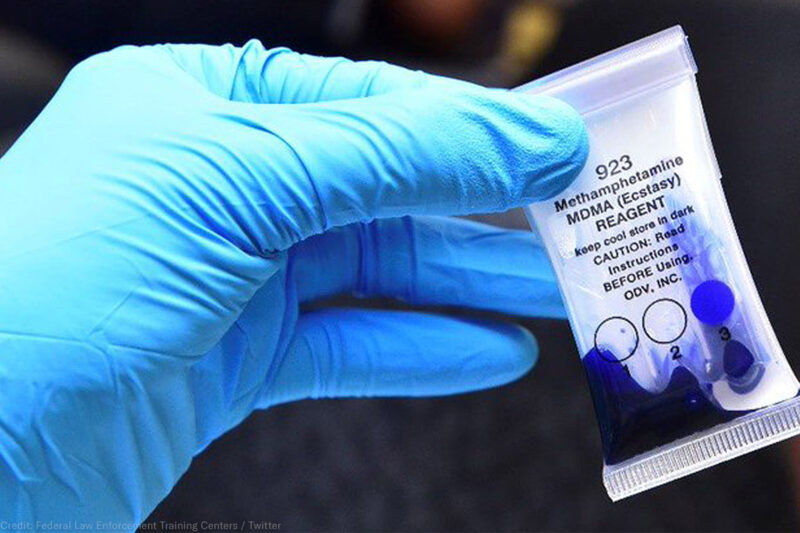

Three years ago on New Year’s Eve, Dasha Fincher was arrested in Monroe County, Georgia, after the deputies performed an on-the-spot test of a bag of blue substance that they found in the car in which she was a passenger. The suspicious stuff in the bag came up positive for methamphetamines. After her arrest, the judge in her case set bail at $1 million because she was perceived as a drug trafficker.

There was just one problem. The roadside drug-test was wrong. The blue substance wasn’t meth — it was cotton candy. Fincher would spend three months in jail because of the faulty test.

Fincher’s story of cotton-candy-gone-meth isn’t an aberration. The prevalence of false-positive results associated with roadside drug tests is terrifyingly common. ProPublica warned that “a minimum of 100,000 people nationwide plead guilty to drug charges that rely on field-test results as evidence” and that because the tests are so frequently used “even a modest error rate, then, could produce hundreds or even thousands of wrongful convictions.”

Despite these gross (and documented) miscarriages of justice, prosecutors continue to seek unaffordable bail and charge defendants with serious crimes that carry high sentences on the basis of roadside drug test results that are unreliable. It doesn’t have to be this way. Local prosecutors can play a pivotal role in preventing these injustices from the get-go.

For instance, the unmatched power of their office allows the prosecutor to end pretrial detention in cases in which criminal charges would be based on a roadside test. Inconclusive, unverified results cannot be the basis of detention. Thus prosecution that relies on these tests must not involve the setting of cash bail. Further, prosecutors must ensure that lab confirmations are prompt. No one should be sitting in jail because the labs are backlogged and because the device used by cops is defective.

This can be accomplished through robust supervision and screening practices, but even in offices that have these practices, there is a need to do more to prevent the incarceration of innocent people or exonerate them. As such, prosecutors and local municipalities should create or expand Conviction Integrity Units to evaluate the prior cases in which these tests were used as evidence in one’s conviction.

This wouldn’t be heralded as monumental reform.

Prosecutors do this already — around the country prosecutor offices review convictions in which misconduct, bad evidence, or error led to the wrongful incarceration of innocent people, but to address false-positives results of roadside drug tests prosecutors need to get proactive. These offices must ensure that the damage done to the wrongfully convicted individual is avoided at all costs.

Not asking for bail in these cases is a good start, but prosecutors must also refrain from pursuing plea deals in cases in which arrest is exclusively supported by a roadside test. This would ensure that the individuals who had been subjected to wrongful arrest are at least free from the pressure of deciding whether to plead guilty for something they didn’t do—just because the lab hasn’t figured out that they’re innocent yet.

Three months in jail for cotton candy doesn’t inspire confidence in the criminal justice system for anyone. At least these recommendations would begin to rebuild the public trust and integrity that false-positives have degraded. If the legitimacy of our system isn’t enough of a reason to prompt change, perhaps fear of paying out large money settlements to the wrongfully convicted would get cities to act on this issue.

In the three months Fincher spent in jail for possession of cotton candy she missed the birth of her grandchildren while waiting on exonerating lab results. Seeking damages, she sued the company, Sirchie, that made the $2 roadside test for the time and life events she can’t get back, arguing that the company negligently designed the product because they “knew or should have known” that the device could lead to false arrests.

To succeed in her claims, Fincher would have had to show that the harm of defective design could have been avoided if the company adopted a reasonable alternative design. Unfortunately, earlier this month a district court in Georgia dismissed her complaint mainly because she included “two purported alternatives” in her response to the company’s rebuttal but the court said she included them “simply too late.”

This is not the first time Georgia protected this company from liability. In a 2017 case, Kerron Brown and Justin Mallory sued Sirchie after each spending weeks in jail due to a false positive. This case was also dismissed because their “complaint contained no facts about reasonable alternative designs” of the drug testing kits.

And there are a lot more people like Dasha Fincher, Justin Mallory and Kerron Brown out there, even in Georgia.

After they learned about Fincher’s story, Fox 5’s Investigation Team started looking into the prevalence of this practice. Based on their analysis of Georgia police records, the reporters found that at least 145 people were wrongly charged with felonies after “a field test falsely claimed they had drugs. Instead of ecstasy, cocaine, or methamphetamines, people jailed actually had common items like incense, headache powder or cleaning supplies.” At least three people were found to have pled guilty “before the lab results came back.”

Our war on drugs has been a moral disaster, but even if prosecutors don’t think that decriminalization, or even outright legalization is the solution, they should put into place protections to ensure no one’s liberty is jeopardized based on a bad roadside drug test. Instead, they should be released until lab results confirm the presence of illegal drugs to guard against turning another innocent person’s life into a nightmare.

There’s no good reason any person should go through what Dasha Fincher endured, and prosecutors have the power to make sure what happened to her never happens again.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.