Sigh. As if we don’t have enough divisiveness in this country, a familiar subset of Congressional Republicans are trotting out yet another discriminatory bill papered over with hollow rhetoric about “unity,” “commonality” and shared national vision, which will be the subject of a hearing in the House Constitution Subcommittee today. (Here’s the ACLU’s statement, which focuses mainly on the civil rights and immigration issues in the bill; I’m just covering the First Amendment in this post.)

Just the title of H.R. 997, the “English Language Unity Act of 2011,” brings to mind that old joke about the Holy Roman Empire (neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire). The English Language Unity Act has nothing to do with promoting English language education, and especially nothing to do with “unity.” But it has everything to do with kicking the First Amendment in the teeth, and picking on the most vulnerable members of our society.

Sponsored by Rep. Steve King (R-IA), the bill does a couple of things:

• It makes English the official language of the United States. (Because in light of massive deficits, rampant unemployment, a slowing economy and the fact we'll probably all be living underground soon due to climate change, this should be our top priority.)

• It requires all "official functions" of the U.S. government to be performed in English. This means, among many other things, tax documents, voter guides and probably signage in federal buildings. The language is broad enough it could even cover public broadcasting.

• It imposes a "uniform language testing standard" for naturalization. That is, it imposes a heightened language test for citizenship beyond what immigrants have been taking for generations. Anybody seeking U.S. citizenship would now have to "understand generally the English language text of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the laws of the United States made in pursuance of the Constitution." Most lawyers I know couldn't pass such a test.

• Finally, and this is the best, it appears to bar members of Congress or any other officer or agent of the federal government from "officially" conversing in any language other than English (but said member or officer may converse "unofficially" in another language).

The legislation has a few other wrinkles, but these four are the First Amendment all-stars. Taking all of these provisions into account, it’s not hyperbole to say that the bill would shut off government access for language minorities.

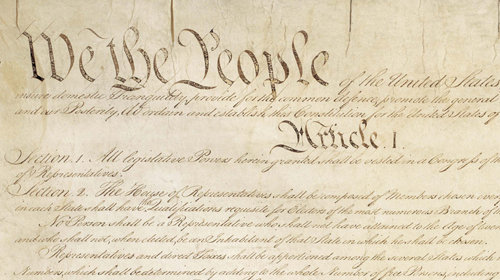

The bill clearly violates both the spirit and letter of the Constitution. Spiritually, the Constitution is a document obsessed with the free flow of ideas (in whatever language) and the accountability and accessibility of federal, state and local governments to the people. These principles inform the First Amendment, of course, but they are also evident in the intellectual property clause, the Speech and Debate Clause and even the Privileges and Immunities Clauses, which reaffirm petition rights across all levels of government.

In fact, you could make an argument that the lack of an official language in the U.S. is part and parcel of this philosophical underpinning. Numerous other constitutional democracies (Canada, France and India, to name just a few) have official languages in their constitutions. In many cases, they’ve done so to suppress regional and minority languages (though, in the case of Canada, the official language policies reflect the historic bilingualism in the country, but also have unintended negative effects on newer language minorities, including, especially, Asian immigrants).

By contrast, in the United States, the unique focus on freedom of expression means linguistic freedom of expression as well. Indeed, in Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), foreign-language education was one of the first cases recognizing a right under “substantive due process” to linguistic freedom, and later Supreme Court decisions have expressly recognized that this Fourteenth Amendment analysis incorporates the First Amendment right as well. The Court found as much in Tinker, the foundational case for students’ free speech rights in school. And, in Griswold, the case providing for a constitutional right to contraception, Justice Douglas wrote with respect to Meyer, “the State may not, consistently with the spirit of the First Amendment, contract the spectrum of available knowledge. The right to freedom of speech and press includes not only the right to utter or to print, but the right to distribute, the right to receive, the right to read and freedom of inquiry, freedom of thought, and freedom to teach . . . .”

The United States should be very proud not to have English as an official language. It’s testament to our national commitment to freedom of expression—unique throughout the world. It’s also testament to our inclusivity (proposed legislation like the Unity Act aside). The hearing tomorrow will showcase one of the ugliest and most insular policy proposals in the United States. I hope it doesn’t receive any more attention than it’s due, which is very little.

(Late Post-Script: Ranking Member Conyers read his statement at the English-only hearing in Spanish! I laughed, but also, that would be illegal under the bill.)

Learn more about freedom of expression: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.