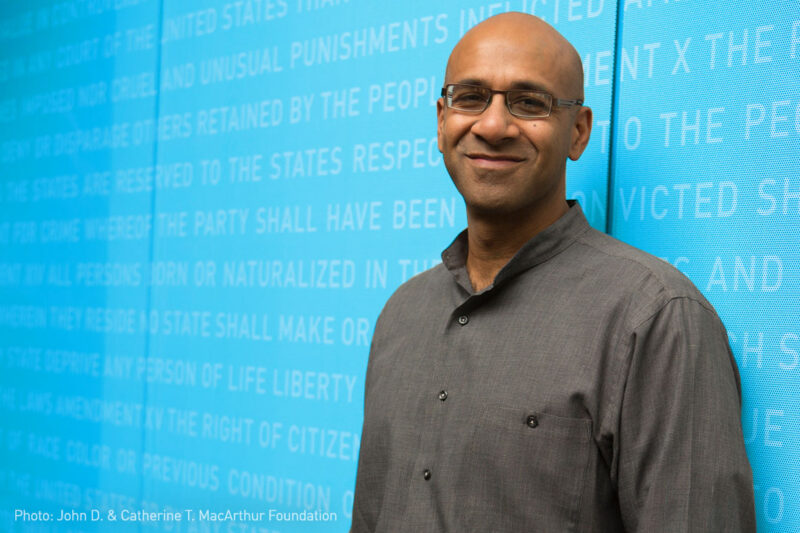

Ahilan Arulanantham, ACLU Immigration Advocate and Newly Minted MacArthur Genius, Explains Why We All Should Care About Immigrants’ Rights

Q: What inspired you to work on immigrants’ rights?

A: I come from a family of immigrants. I was born here but my parents are Sri Lankan Tamils. They came to this country when there was sporadic violence and widespread discrimination against Tamils in Sri Lanka. And when I was 10, the civil war started and most of my extended family left Sri Lanka, and many of them came to live with us for several years.

When I was a child, I saw first-hand the pain and the challenges that displacement causes. Some of my cousins came and lived with us for different reasons without their parents. The parallels between that and what’s happening with Central American children are very real and immediate for me.

Q: What would you like to do with the prize money?

A: I haven’t figured that out yet. I want to give a portion of it to some particular organizations doing good human rights work in Sri Lanka. I feel passionate about those issues but haven’t been able to devote my life’s work to them as I have to immigrants’ rights.

Q: What do you think is the biggest misconception about this kind of work?

A: I think people looking at our immigrants’ rights work often do not take the time to put themselves in the shoes of the people we represent. They say, “These people are illegal. You break the law, you get what you deserve” — that kind of thinking. If they could just sit for a minute in the shoes of my uncle, whose son was diagnosed with a very serious illness right around the same time the war broke out and they had to flee, or my uncle whose whole nice apartment was just burned to the ground and feel the terror of that moment. They still might not agree about what the right policy answer is, but they would view all of our work through a slightly different lens.

Q: Is there a particular case that you’re most proud of?

A: I’m very proud of Nadarajah v Gonzales. It’s the case of a Sri Lankan Tamil refugee who was held as a national security threat for four years. He was wrongly accused of being a member of a Tamil terrorist organization, which he was not — he was a farmer. It was a factual mistake, but the government took the view that they don’t have to give any due process to people stopped at the border seeking asylum. The government’s view was that they could hold him whether or not he was a threat, that people stopped at the border have no rights to be not imprisoned.

We won it after almost two years. He got out. He lives in Lancaster, California. He got married; he has a child.

Q: What has been your most devastating loss?

A: JEFM v. Lynch, just a few days ago. It’s a class action seeking to establish a right to appointed counsel for children who are being deported. The government pays a prosecutor to argue against the child in every case. We’re arguing that due process requires you level the playing field, and the kids should have lawyers too.

The case was made more urgent by the dramatic threat of violence in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras over the last several years. It’s not an exaggeration to say there are thousands of children whose lives are at stake.

If they receive an attorney, they’re far, far more likely to be able to present and win their claims for asylum. If they do not have an attorney, it’s virtually impossible for them to do that.

The court essentially said we had no right to bring this case as a class action for all these children. Instead if children believe that they have a right to an appointed lawyer, they have to appeal that in their individual immigration case and present their claim that way.

I think the court really both misread the law and failed to understand the plight of those children. Honestly if I could, I would trade the award in a heartbeat to win counsel for children.

Q: How does it feel to win this award on the heels of that loss?

I take it as an award for all of the immigrants’ rights advocates, both inside and outside the ACLU, who have worked on these issues with me. I have been lucky to have amazing mentors and partners at the ACLU from the time I first came to work here in 2000, and this award belongs to all of those people.

Q: You and your wife recently had a baby. Does having a child change your perspective on the work you do?

A: My daughter Ananya is 8 months old. I think I had some sense of the long view before, but I feel it more now. I think often actually about when she is 20 or 30, what will the state of human rights look like? I hope people view immigrants and refugees with more empathy than now.

For more information on the award, see the MacArthur Foundation website.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.